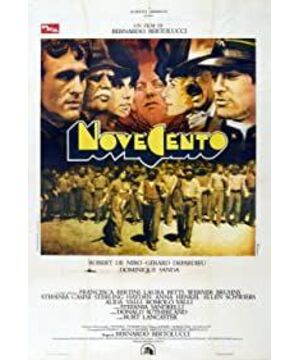

When I was watching Sergio Leone's "Revolutionary Past", my most interesting and favorite story was the three flashbacks of Sean played by Cobain before participating in the Mexican Revolution. The flashbacks were filmed. It is very beautiful. The ambiguous emotions of two men and one woman, the betrayal of close friends, and the sincere romance make people curious about this past event. Until I watched "Nineteen Zero", I was pleasantly surprised to find that Leone did not tell this story, but Bertolucci constructed a greater revolutionary past. It is also an era epic about revolution. The starting points of "1900" and "Revolutionary Past" are completely different. There is no war, no cannons and explosions, no life and death, and no bloody battles in the story. Some are just plain pastoral life, the hardships and sorrows of the proletarians. But the story of what has happened on this land for nearly half a century—and the world—is unfolding before our eyes. As a leftist director, Bertolucci was still a member of the Italian Communist Party until his death. He had great sympathy for the proletarians, for these landless peasants. Unlike the insidious cunning in "Seven Samurai", it is not like the brutality and disorder under Leone's lens. The peasants in "1900" have only a simple ignorance and are powerless to resist this innate exploitation, because in old Leo's view, the son of a peasant is always a peasant. If the story goes on like this, Omo and Alfredo Jr will be like their grandpa: Diligent tenant farmers and gentle and noble owners. But times have changed. The twentieth century has illuminated the world like a light. Machines, guilds, revolutions, infinite new things shatter the default rules that have existed in this land for centuries. The oppressed people don't know what class is, they don't know fascism, and they don't know what communism is. They only understand the scythe and pitchfork in their hands, they follow the simple instinct of survival in their hearts, and they are led to create a new world. Bertolucci pinned his communist ideals in the film, even though some of the stories never happened in Italy. Little Alfredo was a weak man. When Omor waited for the train to fly by under the tracks, he watched; when Omor returned from the battlefield, he could only play as a captain; when Omor faced the tyranny of Attila , he didn't say a word; when Omo became a guerrilla legend, he hid in his family's big house. He was powerless against fear, against his father, against fascism, against class. From this point of view, what if he is a good man, he is still the landowner Alfredo, and his contempt for farmers is etched in his bones, even in the face of his best friend. Talk to Omer about Ada: "No, she's an incredible woman. She smokes, she drives, she writes poetry. A modern woman anyway. You don't know her and you can't understand her. Because you are Farmer." Yes, they grew up playing together, but he still looked down on Omo. It's a weird and complex emotion, I read about arrogance, ego, and even a little bit of inferiority, I think, he looks up to Omo in his heart, and he sympathizes with these farmers and is afraid of losing everything, including his favorite Aida. Omo and Ada are the most suitable pair, one brave and unrestrained, the other passionate. Regardless of age and class, Ida understands Omo better than anyone, and only she can understand that Omo, who was driven out of the village by Attila, is happy. At this moment, she found the resonance between herself and Omo's soul. She looked down on little Alfredo who buried herself in the soil and decided to start pursuing her own happiness. So, until the end of the film, Ada never came back. However, the struggle and ideals of the Omo people finally dissipated in that era. The war was over, the fascists were overthrown, and the landowners disappeared from the world, but the new government took away the guns and weapons, and the peasants accepted everything, they did not become the real owners of the land. I believe that Omo's confusion must also be the regret of many people. At 315 minutes, the movie is probably the longest stand-alone work I've ever seen, but I didn't notice it at all. get boring. Because of all your curiosity about that era, about classes, about revolutions, including all kinds of people who drifted along in the turmoil. All in Bertolucci's films. I also like this ending which is praised by everyone. At the end of the story, the old Omo and Alfredo, who were arguing with each other, came to the railroad track that brought a new era. Alfredo lay down, but this time with his head and feet on the rails. Omor leaned against the tree to say something, but he smiled. When the train finally passed, and Alfredo, who was lying on the rails, turned into a young man, Morricone's melody sounded, filled with emotion. When the wheels of the times pass by, can we see through all our disguises, go back to the origin, and find the little boy in the deepest heart?

View more about 1900 reviews