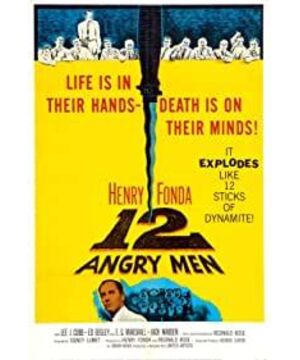

More than 50 years ago, the American director Sydney Lumant directed a classic old film "Twelve Angry Men" (Twelve Angry Men). Its plot is quite simple: a teenager was tried in court as a suspected father murderer, and there were two against him. A very unfavorable witness testimony (an old man, a woman), and an exhibit (the knife in his father’s chest happened to be exactly the same as the one that the boy claimed to be missing). A jury composed of twelve jurors must reach a consensus within a limited time, otherwise it will not be able to make a verdict on the juvenile.

This film was once widely discussed in domestic academic circles as a model of political philosophy. The focus was on the question: Can people in a democratic society achieve cognition of truth by arguing with each other? Professor Ni Liangkang believes that for mutual reasoning to be possible, two conditions need to be met. One is that mutual reasoning contains the presupposition of the "reason" of the argument that needs to be obtained; the other is that mutual reasoning contains the argumentation activity itself. The "rationality" (speaking noui legontas sensibly), and this rationality is commonly recognized (something common to everyone: logos). Professor Chen Jiaying and Professor Wang Qingjie both wrote articles to respond to this point of view. This controversy took place six years ago, and it is rare in the domestic philosophical circles to conduct detailed discussions on a text and theme, and interact with each other for several rounds. Recalling the old things today, the author does not want to comment on the gains and losses of the parties involved in the discussion, but directly from the film text of "Twelve Angry Men", try to do a detailed case analysis to explore the typical-but It is not "ideal"—in a dialogue environment, whether it is necessary to presuppose truth and whether the consensus reached through dialogue is truth.

From a legal perspective, this trial or public deliberation has two prerequisites:

1. The Anglo-American law system makes a "presumption of innocence" on a suspect, which means that unless there is conclusive evidence that the juvenile did commit a crime, he cannot be found guilty. Therefore, in order to be found not guilty, it is only necessary to raise a "reasonable doubt" on the testimony of the two witnesses and one exhibit mentioned above. It is worth noting that this legal setting shows that in this case, there is actually no "positive determination" of the facts. The jurors do not need to provide conclusive evidence that the juvenile did not kill, but only need to provide reasonable grounds for proving the juvenile's guilt. Suspicion is enough-this line of thinking fits with the point we have repeatedly stated before: we will never know the truth about the "primitive" and "naked" reality. What we can do is to exclude all relevant alternatives. And thus reach a consensus;

2, it must be passed by unanimous, not a majority rule. The design of this system is closer to the direct democracy Rousseau aspires to or the deliberative democracy that some deliberative democracy theorists aspire to in terms of spiritual temperament. The majority decision is born for the purpose of "making collective decisions." It is very likely to sacrifice the opinions and interests of a few people. Its basic spirit is to achieve political results even at the expense of truth. Although the unanimous opinion does not guarantee the truth, it at least allows the opinions and interests of all participants in the discussion to be given the fullest attention. We know that it is almost impossible to reach unanimous opinions in a large-scale, multi-valued "stranger" society. If possible, it is also very likely to be achieved through some kind of authoritarian or ideological propaganda (think The experience of the Soviet Union and the Cultural Revolution is not difficult to understand), but in this film, in a small jury composed of 12 people, the probability of reaching unanimous consensus through non-suppressive means is much greater, so how is it possible? Woolen cloth? Can it be achieved through the rational arguments of free and equal people?

The video begins.

The first thing that catches the eye is the strange faces of all beings: in a meeting room less than 20 square meters, there are strangers from various backgrounds. There are stock brokers, salesmen, watch dealers, and cleaners. There are retired old people, there are violent middle-aged men with a tense father-son relationship, and of course our protagonist Henry Fonda, a benevolent, rational and always agnostic detective. Such twelve people serve as jurors because of their political obligations. Suddenly they hold the power of the life and death of a young life in their hands. Their psychological states are naturally different. They are not only the excitement of having power in their hands, but also the waste of time and money. Complaining and chattering endlessly.

After the organizers took the trouble to say "Let's have a meeting" three times, the first voting officially began. Before, people did not communicate and communicate about the case itself. Everyone just made their own judgments on the case from their own position, point of view, and the information they had learned-everything resembled the most popular and well-known form of democracy today. : Take voting as the center, express one-dimensional personal will and tendency. The result of the first vote was 11:1. Eleven people were found guilty and one person was found not guilty. At this time, the unanimous mechanism came into play, and the jury was unable to make any decisions. Therefore, when the only dissident-the detective played by Henry Fonda, "untimely" proposed: "Let's talk" and "Let's talk about our views", dialogue and communication-this The elements of deliberation democracy come into play. But be careful, there does not seem to be an "ideal speaking environment" as Habermas calls it, because although everyone is free and equal in law, in this "typical speaking environment" the interlocutor’s society Identity and status background are factors that cannot be avoided at any time, while so-called "rational" dialogues are rare.

We found that under Henry Fonda’s repeated insistence, the jurors who advocated that the guilty party was the first to waver had a common feature: they were all from disadvantaged groups in society. Under the special situation of the jury, the psychological mechanism of the socially disadvantaged groups presents an extremely interesting picture. On the one hand, because of weakness, they are more susceptible to other opinions. In fact, we found that the three jurors who still insisted on their opinions were either the three with the strongest character or the strongest social status; on the other hand, because of weakness There is more and more the psychological need to highlight the self, the more eager to get the approval of others, and therefore the more inclined to express dissent. These two seemingly conflicting factors are superimposed together. Under the situation where unanimous consensus is required to arrive at the final result and the specific voting result is 11:1, a strange scene is produced: those jurors from socially disadvantaged groups. Prefer the minority party (ie Henry Fonda) rather than the majority party.

Someone will immediately retort: aren't the disadvantaged people more inclined to go with the majority? Indeed, disadvantaged people are usually more inclined to agree with the majority, but this is not contradictory to the disadvantaged people are more likely to be influenced by other opinions. The two are not contradictory. One is the other; the second is whether it is the old man or the cleaner. Although they are in a disadvantaged position in their daily lives, a sudden opportunity allows them to get along with others on an equal footing and share the same weight of one person, one vote. This makes them find the best in their frequently offended and provocative self-esteem. The breakthrough point, the expression of dissent becomes more and more precious. This is especially true when they contribute a unique observation of their own through their own "hard" thinking. (For example, the old man "proudly" pointed out that the elderly eyewitness must have witnessed the suspect with his own eyes; the cleaner used his slum life background to tell everyone that if a teenager commits a crime, the posture of the knife must be inconsistent with the wound on the chest of the deceased. )

Another interesting phenomenon is that when the juror changes from claiming guilt to claiming innocence, it is acceptable, but it is unacceptable to change the position again. Here comes the question of self-identification: Are you a capricious wall rider? We have seen that in the film, except for the salesperson who is used to behave like a rudder (this habit is a good professional character for salespersons, but unfortunately it does not apply here), the others are determined after changing their positions once. Do not move, but do they really believe in it? Actually not necessarily. Moreover, after the salesperson was accused by the "two-faced" and he accepted the result of the innocence again with a sad expression, he had nowhere to go, and could no longer return to the conclusion of the guilt.

In the process of conversation and argument, two factors are crucial: The

first is Henry Fonda’s personal charm. This is an extremely good political demagogue. He almost dominates the entire discussion and is good at To occupy the moral high ground in time in the debate, such as the emphasis on the “slum” background of the juvenile suspect, and the accusation of the lack of sympathy and kindness of the opponent in the debate. This obviously has a hypnotic effect on other people who have similar backgrounds or who are more compassionate in the discussion. On the contrary, the most powerful guy in the opposition is a arrogant, chaotic and arrogant. When he argues with Fonda in a furious way, his winning or losing has been judged, which can be no exaggeration. It is said that the reason why most jurors who support the determination of guilt abandon their original views is not unrelated to the negative image of this person.

Second, Henry Fonda "well-founded" raised the so-called "reasonable suspicion" of the existing evidence: the old man downstairs may have misheard the beating and scolding, because he may not be able to walk through the whole in 15 seconds. The corridor then witnessed the suspect rushing down the stairs; the woman may be short-sighted, so it is very likely that she could not see the real scene of the murder; the young suspect’s knife might have been picked up, and the reason why he could not remember the name of the movie might be because he was too short-sighted. Nervous... and so on. It should be noted that no new evidence was introduced in the entire argumentation process, but permutations and combinations were made on the basis of the original evidence, and “reasonable” doubts were made from various angles. However, in my opinion, the so-called reasonable doubts here The rationality is actually questionable. We know that there is a school of knowledge in the theory of knowledge called "relevant selectivity", which means that not all doubts are related doubts. Many of the doubts raised by Henry Fonda in this film seem to me to be such irrelevant doubts.

There is one detail worth mentioning. Among those who insist on juvenile guilt, the stock economist is the most rational and calm. He insisted on the determination of guilt for two reasons: 1. The reason for the juvenile suspect’s claim that he was not at the crime scene was at the time. While watching a movie, the teenager was unable to provide the name of the movie and the name of the protagonist; 2. A woman once witnessed a murder.

Henry Fonda believes that both reasons for stockbrokers can be doubted. He criticized the stockbroker like this—perhaps better with inducement:

Fonda: What did you do last night

Economist: Go home after work

Fonda: What about the night before?

Economist: Dinner with his wife

Fonda: How about the night before yesterday?

Economist: The day before yesterday...it seems to be...

Fonda's intention is simple: memory can be wrong. But his method of argumentation is tricky. I really don’t remember what I was doing at 8:34 p.m. 789 days ago, but this can neither be used as relevant evidence to prove that my memory is poor, nor can I prove that others’ memory is poor, and more importantly, it cannot be proved. All memories are wrong.

The most dramatic scene appeared in Henry Fonda's persuasion of the violent middle-aged man. At this time, the ratio of found innocent to guilty has turned back to 11:1, but the violent middle-aged man is still resisting, until Henry Fonda takes the lead and makes the latter realize that the reason why he believes that he is a teenager is due to the tension between him and his son. Relationship, the so-called "hate house and black". Looking at the changes in the positions of the remaining 10 people, it is also not the result of rational arguments. On the contrary, most people change their positions because of their identity, status, and psychological conflicts. This is particularly evident in the cleaners and the elderly. .

This film depicts the whole process of argument in the form of group portraits: from dissent, debate, persuasion, quarrel, reasoning to consensus. What it shows is the process of how different discourse forces compete with each other to reach a consensus in the process of actual speech, communication, and argument, but this consensus does not point to the truth. Ni Liangkang quoted Heraclitus in the article: If we want to speak rationally, we have to put our strength on this common thing (ie Logos). Heraclitus’s words are correct. The one who is wrong is Ni Liangkang, because Ni Liangkang took the ancient Greek logos too narrowly. In ancient Greece, logos removed rationality, and there were rhetoric, metaphors, analogies, etc. In this film, there are also impurity factors such as identity, class, relationship, emotion, Calisma and so on.

At the end of the film, Henry Fonda said two sentences when he stared at the last stubborn opponent with piercing eyes. One sentence was "We raised reasonable doubt" and the other sentence was "You are alone." The first sentence is meant to tell the other party that the truth is not on your side (although it may not be on my side), while the second sentence is to say that most people’s opinions have now abandoned you.

When the twelve angry men finally left the jury room, they did not walk out of Plato's cave. They did not see the shining sun, but disappeared into the twilight suspiciously. However, this is sufficient for a legal system based on the presumption of innocence.

Maybe the truth is still somewhere, but the truth is not here.

by Zhou Lian

View more about 12 Angry Men reviews