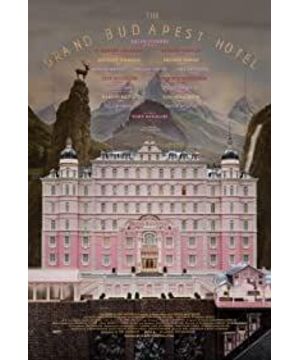

The movie "Budapest Hotel" has conquered countless fans just by its beauty. Each frame of its picture has a pleasant symmetrical composition, a matte tone full of dreamy atmosphere, like a delicious cake, a fragile bubble. There is a devil in the details. In addition to the intuitive "beauty", every set of costumes and every scene design has hidden mysteries.

The following content and pictures are taken from the book "The Grand Budapest Hotel: A Collection of Works by Wes Anderson", published with the authorization of the publishing house.

This article was first published on WeChat public account: Beijing News Book Review Weekly, welcome to follow.

Original Author丨Christopher Liverty/Steven Boone

Excerpts | Xiao Shuyan

01

Wearing is Man: The Art of Film Costume

On the screen, we can learn a lot about what a person wears. Clothing serves multiple aesthetic levels in the film: roles, narrative process, chronological accuracy, and visual wonders. How a film is remembered in public consciousness is also closely related to clothing. The most amazing costumes may gradually become a symbol of the movie itself in memory: Scarlett Scarlett’s velvet curtains and dresses in "Gone with the Wind", the gangsters in "A Clockwork Orange" (costume by Milena Canio) Designed by Nero), a white dress, a black top hat and a crotch cloth, an Indiana Jones leather jacket, a trilby and a leather whip. They are just like the costumes in the "Budapest Hotel". They can be the objects of careful observation and obsession, or they can be just the right existence in the context of the film: you don't have to pay attention to the details of the costumes, but if you choose to pay attention, the details may be revealed more. For far-reaching significance.

Anderson often puts on uniforms for his characters. Sometimes uniforms mean specific occupations, such as the "Lawn Ranger" in "Bottled Rocket" and the crew of the Belafonte in "Life in the Water." Sometimes, uniforms are a kind of self-creation, representing the character's perception of themselves or the world's perception of them. Costume is a character's armor, their subtext, or more crucially, a visual trick. When the armor is broken or abandoned, the audience will immediately notice. We can understand the inside of characters by studying the outside of the characters, because the clothes are the people.

At first glance, Agatha is just a typical pastry girl wearing a sweet-toned pistachio green dress, pink cable-knit sweater and thick woolen socks. But as the storyline gradually unfolded, she harvested a porcelain pendant of the Cross Key Alliance, which is a symbol of her becoming one of the most important characters in the film. We have learned that this badge is usually only worn by concierges who have joined that well-known alliance. But because of Agatha's resourcefulness, Gustav thought she could bear the honor. And Zero was still immersed in mourning after becoming an elderly man. He wore this pendant to comfort the thoughts of the lost love.

Mrs. D is dressed in a Klimt-style coat, and next to him is Gustav in uniform.

As Gustav turned from a symbol of luxury and tradition to a contemptuous prisoner, he also took off his custom suit and replaced it with a striped prison uniform-the sleeves were too short, the trousers dangling around the ankles, and the feet were stepped on. A pair of heavy wooden shoes. He seemed to have accepted this little indecent with a relatively optimistic attitude, and even said nothing about the greater insults that followed; but we would be curious, Mrs. D, who always wore a Klimt-style velvet gown. , If she hadn't passed away at this time, what would it be like to see her always well-dressed lover so downhearted? The old lady's dress symbolizes the pinnacle of hotel culture: the glorious age of parties and champagne, four-poster beds and foie gras.

Joplin's knee-length leather trench coat has a solid, hard silhouette, practical and style. The prototype of this costume was a German leather coat during World War II. It was essentially a motorcycle messenger jacket, designed to keep the wearer warm and dry. Although Joplin, dressed in black, looks like a typical villain in a parody version, the audience can't laugh because of the horror myth. His vampire Nosferatu-like fangs and skull-shaped knuckles, and under the gun block of his coat (which should be on the map) hide a gun, a bottle of wine, and a crushed ice cone. However, even these most sinister violent equipment did not overly diminish the comic meaning of the character itself.

The sharp-eyed audience may have recognized the half-striped design of the backs of the three brothers' jackets in the director's fifth feature film "Crossing Darjeeling" (a tribute to the classic Norfolk suit). The old and young writers in "The Grand Budapest Hotel" are all dressed in full Norfolk suits. From the Victorian period to the 1920s, people generally believed that the Norfolk suit was a kind of sportswear. On the screen—especially outside the countryside—a person wearing a Norfolk suit shows that he is a gentleman with extensive travel experience, a wanderer far from his homeland, and a person similar to our writer. The precious time spent with Zero changed his life.

02

The magnificent stage: setting and art design

With meticulous design, colorful colors and ornate decorations, Wes Anderson's movies are usually described as a doll house or an exquisite candy kingdom. Such a reputation may give people the impression that most of Anderson's works are limited to the setting, and the work is full of delicate installations. In fact, what the screenwriter and director seeks is stylization [toy-like art design with both form and function, LB Abbott's "wire, tape, rubber band" special effects] and realism (with The balance between psychological-based performance and shooting with pre-existing locations). This balance brings a unique tension to his films. In the "Budapest Hotel", this kind of binary game is also used to describe Europe in the age of industrialization, expansion, war and genocide: Vienna, Paris, London, and Berlin, such as elegant and sophisticated cities, have gradually fallen into In the shadow of the systematic atrocities of the world war.

It is the photographer Robert Yeoman that allows these two opposing forces to merge with each other instead of colliding with each other. Adam Stockhausen's art design draws a lot of inspiration from Edmund Goulding's "The Grand Hotel", and also refers to other classic movies of the 1930s and 1940s, such as Ernst · "The Troubles in Heaven" and "The Corner Shop" by Liu Bieqian, "A Story of Princesses" by Ruben Mamoulian, "The Missing Lady" and "The Missing Lady" by Alfred Hitchcock Thirty-nine steps." However, Yeoman seldom adopted the strong directional and clear shadow lighting style in these films. Colors dominate in Anderson's world, not black and white tones. Speaking of color alone, the full-color early 20th century in Anderson's films also has a nostalgic color, but this nostalgia is closer to the memory of people who really lived in that era, rather than just the romantic imagination of the world war through black and white movies. Kind of nostalgia. Soft and bright lights are also commonly used in glamour lighting. They flow out from lampshades or reflect off cream-colored walls. This is romantic realism, which was inspired by Wes Anderson’s two main sources of influence-François Truffaut and Louis Mahler through New Wave photographers Henri Decaë and Raoul Raoul Coutard's lens is brought to the screen. Light induces us to regard the environment as an extension of the character, and we also have our own weird personality.

The Grand Budapest Hotel (the shooting location is actually a department store) in 1932 is a pastel art nouveau whimsical world. Mr. Gustav, the chief concierge and companion of the noble lady, has a deep understanding of this style. Nostalgia, but as early as when he became a concierge boy, this style has been outdated. In the 1930s, modernism blossomed everywhere, but it did not receive the slightest attention from Gustav. The big hotel we can see still maintains the appearance of his youth, and it is the toy box he has used for a long time to gain a sense of superiority. This space paved a magnificent stage for his market, sophistication, cynical and lofty ideals. All the exterior scenes of the hotel are miniatures made by Simon Weisse according to the ratio of 1:18, so it seems logical.

The second act of the movie’s madness begins in a gorgeous mansion named "Lutz Castle" [the exterior is taken from Castle Hainewalde in Saxony, Germany, and the interior is taken from Schloss Waldenburg]. Like the evil twins of the Budapest Grand Hotel. The soft warm colors and luxurious comfort of the hotel exude the luxury and thoughtfulness of being at home, while this gloomy hardwood-decorated castle declares wealth from a high level. Its interior rooms are as complicated as a maze, even if it is the residence of Dr. Frankenstein in the Universal Pictures horror film or the Nazi headquarters (Heinewald Castle was indeed confiscated by the Nazis in 1933).

The loot room is the cruel core of the building, where the will of Mrs. Desgow-Taksis, Gustav's elderly lover, is read out. Around this room, it is not so much decorated as to discard prey heads, horns and torso specimens. In addition, the room was also full of "relatives" sitting shoulder to shoulder. Although they were dressed in plain funeral clothes, their eyes fell greedily on the executor Kovac (like an owl professor who teaches funeral home). , Like waiting for the lottery numbers to be announced. The dark green and gold embellishments on the walls can hardly alleviate the overall feeling of being trapped in the tomb. Just one glance at Mrs. D’s son Dmitry—a tight black robe like a crow, with a harsh moustache and grotesque hairstyle—we know where the atmosphere of this room comes from.

From flickering candles to large brown wooden decorative surfaces, at least the warm colors can still find a place in Lutz Castle. And when Gustav, who was imprisoned for (framed) murder, arrived at checkpoint 19, we no longer had any luck with warm colors. The gritty side of Gustav's soul began to show in this crumbling blue-gray tin box. He was no longer just the flashy playboy, but a survivor who refused to admit defeat-only God knows where this temperament came from.

Max Opheles might point out that the glitz of the upper class represented by the Grand Budapest Hotel is supported by unspeakable suffering and violence in society. Gustav is no stranger to these dark sides, and there are a lot of destructive hints in the film. Gustav was able to cope with all kinds of brutality and violence in many European hotels, and he was able to tirelessly maintain the courtesy and courtesy of the Budapest Grand Hotel in prison. Is his elegance inborn? Is his roughness learned? There is a comedy highlight in the film. He invites inmates to eat a box of Mendel's Pastry House snacks, which is a luxury that can be compared with truffles and caviar. The prisoners, dressed in gray prison uniforms like concentration camps, huddled together in a picture frame made of blunt stone walls, staring in awe at a pyramid-shaped sweet pastry, as if looking up at the incarnation of the Budapest Grand Hotel. Here, art design plays a role in sublimating characters and social commentary.

This is one of Anderson's cruelest movies. The selection of historically significant scenes in the film casts a disturbing background behind every atrocities. The only exception was the totally whimsical climax of the gunfight, in which the camera slid laterally between the shooters on the top floor of the hotel. But in addition, most of the violence and killing passages in the movie are soaked with dark background. The mahogany decoration of the loot room and the gloomy atmosphere of the walls envelop Dmitry's running dog Joplin like a cloak. He followed the scene of Kovacs running through the dim museum all the way, emulating the KGB chasing Paul Newman in Hitchcock's "Breaking the Iron Curtain." For Anderson, the world is gradually engulfed by darkness in violence, loss, and even extreme emotional contempt. This is also reflected in the changes in the film scene, sometimes even in a single shot. When Zero, who was already in his old age, recalled his beloved Agatha who died young, as a strong side light swept across his face, the lights in the dining room of the Budapest Grand Hotel dimmed.

This is Anderson’s enthusiasm for anamorphic lens photography inspired by Truffau’s early works (plus Yoman’s talent). He also introduced "Youth", "Genius Family", "Aquatic Life", "Crossing Darjeeling" and " Some visual components of the scenes in these very different films of "The Grand Budapest Hotel" are combined together. He only used anamorphic lens photography in the 1960s scenes of the "Budapest Hotel", which technically coincides with the James Bond era of widescreen. The wide-screen picture ratio is also appropriate for expressing the illusion of equality of all strata during the communist regime. Of course, as always, Anderson’s main purpose of using this form is when F. Morrie Abraham's Zero Mustafa tells of his own experience (the slight distortion of the anamorphic lens and the softness of the oil painting in the defocused area can Add a touch of mystery to the scene), and strengthen the solemn and nostalgic memory surrounding the character. Although the Grand Budapest Hotel is a relic of decay, the utilitarian boringness buried the old magnificent gilding, the distorted optical effect still allows us to look at this place through Mustafa's heavy mental perspective. We can almost see ghosts traveling around.

However, the lowest point of Anderson's film emotions is not darkness (he described darkness as an inevitable fact in life), but a world that has lost its color and diversity—there are only rigid and ugly choices left. Either black or white. We quickly saw the events that took place in the train carriages. The tone of the picture was black and white. We naturally thought of military brutality. Soon we learned that this overture played the death of Gustav not shown in the picture. The black and white tones of this passage are consistent with the black and white meanings in Chaplin's The Great Dictator, Frank Borzage's Deadly Storm, and Spielberg's Schindler's List. It not only opened a horrible history, but also ended Gustav's illusion of civilization.

The last set of shots of "The Grand Budapest Hotel" constructed the narrative outlet through the narration of different characters, which took us step by step away from the story. Mustafa first summarized the story of Gustav, and the writer also summarized the Memories of Fa, both narratives show what the former called "a marvelous grace" (Zero’s original words on Gustav): Mustafa first solved the riddle — why he Still have a deep attachment to this fading and unhappy hotel? Afterwards, the elevator doors slowly closed in front of him like the final curtain of the play. The writer went on to confess that he had never seen Mustafa again, nor had he returned to the hotel. This sentence started by a young writer. When we said the first half of the sentence, we saw him writing in a hotel lobby in the 1960s; when we said the second half, the picture shows him who is old, still writing, but already in the 1980s. Home. Then the picture cuts to a young girl who seems to be full of books. She has been sitting on a bench near the monument to the now-deceased writer and reading this story from beginning to end. This series of moving shots full of resonance and identification are not highlighted with close-up shots, but with panoramic shots of characters. These characters are very small against the background of the scene, trapped in their own time. In an instant, they touched each other through printed words.

I suspect that what gives this montage special impact is a short shot in front of it. That was the last time Gustav appeared. He and other hotel employees stood under the giant landscape painting that many people would call kitsch in the dining room, posing for a photo. The whole picture is top-heavy due to the excessive emphasis on the upper part, so that the audience can only glance at Gustav quickly. Please pay special attention to Anderson's "careless" handling. Here he uses the setting to speak for the character he loves-the person who is personable, proud and vanity, full of flaws, comical and exaggerated, and at the same time has a heart that is as great as the size of the oil painting in the picture, and it is difficult to ignore. Anderson wanted to say, look, this is a life that fascist bastards instantly wiped out. Although he belongs to all living beings, he is unique.

This article is an excerpt from "The Grand Budapest Hotel: A Collection of Works by Wes Anderson". Editor: [German] Matt Zoller Setz; Excerpt: Xiao Shuyan; Editor: Shen Chan; Proofreading of the lead: Li Shihui.

This article was first published on WeChat public account: Beijing News Book Review Weekly, welcome to follow.

View more about The Grand Budapest Hotel reviews