Author: Roger Ebert (rogerebert.com)

Translator: csh

The translation was first published in "Iris"

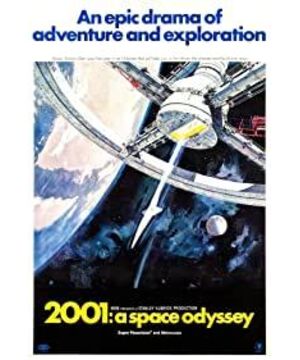

A good fable will explain itself. When you finish reading the story about Lazarus in the Bible, you don't need to ask anyone for answers. I believe the same is true of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. So why does this movie still make so many viewers angry and confused? I went to watch this film again last week and I was surrounded by the murmurs of many people, some whispering people trying to figure out what happened, and others just killing time. I guess they may be making a shopping plan. After the movie was over, someone suggested that MGM should conduct an IQ test on people before allowing them to enter the theater. I can understand this argument. If people can’t shut up politely while watching a movie, they should at least be assigned to a special matinee for children on Saturday, no matter how old they are. Silence and attention are very important in "2001: A Space Odyssey" because this is a work that puts forward a complete statement. You may not be able to understand a fragment of it, but only after you have seen the whole work, can you go back and fill in the missing places. However, when it appears on the screen, you should simply recognize it. Don't ask questions, don't whisper, give this movie a chance. Because "2001: A Space Odyssey" is a work that needs this way of viewing, I think it deserves a better opportunity among young audiences. Kubrick himself believes that this film will not have too much luck, because the audience grows up watching "linear films"—that is, films that follow the plot line from beginning to end. When watching a linear movie, you will never ask why John Wayne killed a bad guy (although you should probably ask such a question). But in Kubrick's film, there are some more difficult questions to answer. For example, what is that huge black slab that followed humans through the Kubrick universe? One night two days ago, the people around me asked many questions about the slab.

Question: What is that huge black stone slab? Answer: That is a huge black stone slab.

Q: Where did it come from? Answer: It's from another place.

Question: Who put it there? Answer: Some intelligent creatures, because they have right angles, nature will not create right angles by themselves.

Q: How many slates are there in total? Answer: Kubrick uses one piece every time he needs it. Now it seems that these answers are all obvious observations. But I guess that the audience does not like simple answers. They want these boulders to "represent" something. Well, it is true, it represents some kind of boulder that cannot be explained. It is interesting because humans cannot interpret it. Wouldn’t it be more satisfying if Kubrick offered some kind of interpretation, such as letting some little green men from Mars put it in the right place? Does everything need to be explained? Some people think so. I want to know how they can endure the activity of "seeing the stars". However, what makes the audience more disturbed is the bedroom at the end of the film. Kubrick's space explorer hit another black slab in Jupiter's orbit, which put him in the distortion of space.

Question: What is space distortion? Answer: It is the distortion in space, which will also cause distortion in time, thanks to Einstein.

Question: So, where is the pilot when he appears in the objective world? Answer: It's in the bedroom.

Q: The bedroom? Answer: Yes, a luxuriously decorated bedroom in the style of Louis XVI.

Q: Why does a bedroom appear in Jupiter's orbit? Answer: No, it did not appear in Jupiter's orbit. This is a bedroom. The pilot played by Kyle Durer looked out the window and found himself standing outside wearing a space suit. He walked out and stood outside wearing a space suit, and then he saw himself sitting at a table inside, eating. He noticed that he was old and dying in bed. He became himself lying on the bed, and then died on the bed. Well, not every space explorer will die in bed. So, where did the bedroom come from? My intuition is that this comes from Kubrick’s imagination. He knows that the familiar bedroom can be the strangest, most puzzling, and most disturbing ending scene. He is right. The bedroom is more detached and weird than any number of exploding stars. We can understand the explosion of stars, but can we understand the bedroom? The man in Kubrick's lens is gradually aging and dying, and the bedroom also provides a suitable background. Why can't it just be a certain background? The poet put his lover under the tree, and no one asked where the tree came from. Why can't Kubrick put his old man in the bedroom? This is what literary critics call "non-descriptive symbols"-that is, the bedroom just represents the bedroom, it has no other meaning. At the most essential level, this film is an allegory about "people". It is what Kubrick wants to express about the "human" view, and it involves the category of race, concept, and cosmic inhabitants. More specifically, this film tells the journey of mankind, first the natural state of using tools, and then the higher-dimensional natural state. The dialogue in the middle of the film is almost unnecessary, they are like background music expressed in words. When humans were still apes and made their home completely natural, Kubrick was already showing us everything. What he showed us is that we have become tool makers in order to control the natural environment. He also showed us the process of using tools to explore space. With tools, we can exist in the universe naturally and easily, just as we were on Earth. The opening paragraph of this film is very exciting. It can be screened as an educational film to explain how humans are used as a tool animal. It is clearer than any textbook. The two groups of great apes yelled at each other. They were frightened by the sound of the night. A huge boulder appeared. A group of great apes touched it cautiously, their hands moving along the perfect, smooth edge. When great apes stroked boulders, their brains There is a situation similar to a short circuit. A certain connection is established between their eyes, mind and hands. Their attention is drawn to an object in the environment, not to themselves. The makers of the boulders taught them a "class"-then they discovered that they could pick up a stick as a tool (at first for killing, then for more subtle purposes). Through editing, Kubrick switched from one of the simplest tools to the most complex tool-a spaceship. This prehistoric bone was thrown into the air and turned into a spacecraft on the way to the space station. Is there anything clearer than this? These are the two extremes in the use of human tools. However, when the people in the space station began to talk (at this time forty-five minutes had passed since the movie), the person behind me sighed, "The story has finally begun." From such a person's point of view, a story is a dilemma. There is no plot and dialogue. For such an audience, experiencing "2001" may be a very difficult thing. Then what? Then another boulder appeared on the moon.

Like the first boulder, this boulder also provides a transcendent experience. By this time, humans are already smart enough that they can realize that this boulder was created by another intelligent creature. For the human self, this is a terrible blow. So he headed towards Jupiter, because the boulder was sending a signal in that direction. Humans brought "Hal 9000", which is such a complex computer (also called a tool) that it may even exceed human intelligence. This is an ultimate tool.

However, this "Hal 9000", made according to human imagination and preferences, also shares human self and pride. In the end, destroying "Hal" became a necessary task-after he almost destroyed the task-so in the end only one human remained, alone facing the third boulder at the edge of the solar system.

At this time, human beings have undergone a new transformation, which is as important as being a tool user. For hundreds of thousands of years, he has been relying on tools to make his own living, but now he has become a natural existence again. Now he doesn't need them anymore. He has surpassed his own nature, just like the primitive ape, he is no longer a "human" now.

Instead, after aging and death, he was reborn as a son of the universe. This is a serious, wide-eyed baby. He scanned the stars and the earth slowly, then turned his eyes to the audience.

In the last twenty seconds, when the son of humanity looked down at the men and women who were his ancestors, the most important moment in this film came. We audiences are still "people", but he is an already liberated and natural existence. Kubrick believes that we will eventually become such an existence.

However, on the night of the first two days, when Kubrick's space baby looked at the audience, half of the audience was anxious to get up and leave. One-third of the audience must have never seen this space baby.

Man is a curious animal. He will feel uneasy in the face of great experiences, and if he is forced to recognize something profound, he will immediately start to belittle it and bring it down to the same level as himself. Therefore, when the great man is assassinated, the little people will immediately make and sell plastic statues, souvenir wallets and lucky coins with the image of the great man.

"2001" is also experiencing the same experience. Two out of every three people who have watched this film will assure you that it is too long, too difficult, or (in the worst case) it is just a science fiction film. But it is actually a wonderful fable about human nature. Perhaps, not wanting to know too much about human nature is also human nature.

View more about 2001: A Space Odyssey reviews