In addition to war, and the nasty thoughts in the human soul (inferior nation, genocide, colonization, and tyranny) behind the war, what else can turn a pianist into a rat in the ruins? You should look at the skinny Jewish pianist wandering and wandering in the abandoned city of Warsaw in 1945. His dirty beard makes him look like Jesus on the cross, but that wretched, yes, as The wretchedness of a lonely exile, the wretchedness of a prisoner of hunger and sickness, made him devoid of human form, but as a musician and a Jew, he did not lose his minimum dignity.

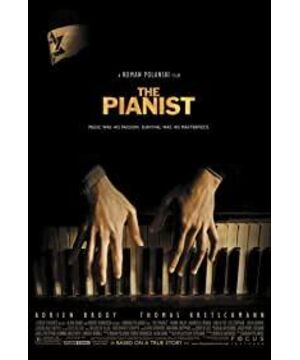

The pianist, his best piano performance was not on Polish radio after the war, not in the brightly lit concert hall, or even his thrilling empty play in the refuge, but in the ruined empty city of Warsaw. Playing for that Nazi officer. I really want to know the name of that tune, because it greatly enhances the movie.

The rhythm at the beginning is very slow, very low, and even a little trembling (half of it is because of hunger, usually because of fear), but it seems to be whispering. Slowly, the rhythm speeds up, faster and faster, faster and faster, like crying, and it seems to be accusing, very urgent, like to spit out a heart, like anger, like roaring... This is not a Jew. The accusation of a Nazi officer is the accusation of the entire weak and dignified Jewish nation against the Nazi tyranny, and the accusation of mankind against absurd war atrocities.

This may be the first time that I truly understand the power of music.

Throughout the film, the director is controlling his emotions, just as Polanski himself said-"You can't see the trace of the director", except here, the piano playing in the ruins brought the movie to a climax with music. It is in this extreme restraint of condemnation and criticism, in this extremely implicit expression of right and wrong, Polanski reproduces the true Jewish history of World War II, which is compared with Spielberg’s preconceived catharsis. Obviously wins. To be honest, sometimes I even feel that Spielberg's display of Nazi atrocities is more of a sensationalism, a kind of display, and lack of emotional investment.

The main part of the second half of the film is the experience of a pianist who was lurking in Poland with the help of Polish friends and resistance organizations and was eventually rescued. In this period, especially after his singer friend left Poland, he became a veritable exile no matter in the external environment or spiritually. The survival instinct allows this lucky guy to escape the chasing of death again and again, but he can't avoid loneliness, boundless loneliness, that is a feeling that any of us who have never experienced that war cannot experience. In the war, an ordinary person has no revolutionary ideals, no relatives or friends, or even his own art. What supports him is the instinct to live.

This is a human exile, and this human exile can happen to anyone.

[Pianist] is telling a story, I think it tells a good story. So much suffering, so many places that can be accused, sentimental, and provocative have been avoided by Polanski using the most concise means of classical narrative. His first pursuit is to tell the story smoothly, no matter how much he wants to express his feelings and ideas, he finally did it. This is something that many directors I know of are increasingly difficult to do. Before watching this movie, I was worried that I would leave halfway through, and that it was too dull, but in fact it felt like I was appreciating the classicism literature in one go. It's full and heavy, but as fascinating as Hugo's "Les Miserables".

View more about The Pianist reviews