http://ent.163.com/09/0430/09/584TLEAP00031NJO.html

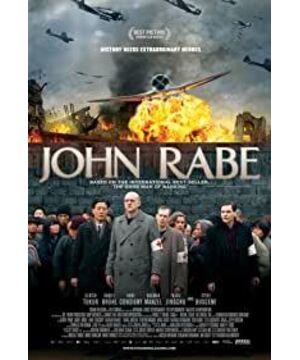

In the just announced German Film Awards, "John Rabe" [Note: In this article, "Rabe’s Diary" "Refers to the book, and "John Rabe" refers to the film] won four awards including best picture and actor, and received numerous nominations, including an Oscar nomination for best foreign language film, "Badr and "Meinhof" returned empty-handed. This does illustrate some kind of problem. In my opinion, in recent years, German films have indeed shown a tendency to look down upon Europe. Take a look at these works: "Goodbye Lenin", "Escape from Berlin", "Perfume", "Eavesdropping Storm", "Badr and Mainhof" and this "John Rabe", as a certain ideological and Films that speak productively and have better market recognition seem to have not had such a scale effect in Britain, France, Spain, and Italy. Of course, the German Film Award (roughly equivalent to the Oscar or the Golden Rooster Award in China) is awarded to "John Rabe" instead of "Badr and Mainhof" itself is a good indicator of the problem, political correctness or some new mainstream ideology The expression played an obvious role in the meantime. In fact, as far as the film itself is concerned, "Badl and Mainhof" is the best German film in recent years, but because it aims to criticize and reflect on the internal pain of the sixties, it does not provide an imaginative It’s natural to give nominations and not awards to the settlement. The award of "John Rabe" probably shows that the way the film is written is recognized by the mainstream.

So let's discuss "John Rabe". It is very interesting that this film has more topic and discussion space in the Chinese context. The first thing to note is that since I did not read Rabe’s Diary and did not collect relevant historical materials, I only provide some entry points for thinking here, and put aside more specific textual comparative analysis for the time being. There are two most clear and direct entrances. One is "Nanjing!" which was screened last week. Nanjing! ", I will give a comparative reading at the end of this article; the second is to analyze now, who is Rabe——

Before "Rabe's Diary" aroused discussion in the Chinese intellectual circles, I believe that people who are not engaged in history or related disciplines probably only have an understanding of historical facts in middle school history textbooks. What the history textbook tells us includes the Nanjing Massacre, the 100-man beheading competition, and 300,000 compatriots who died; what the history textbook does not tell us is John Rabe’s safe area, and John Rabe, who was killed in the movie. Shaped into a tragic hero. This is the other half of the story, and as far as I am concerned, this matter has to be told from the outside, whether it is through books or movies, rather than from the context of China itself, this matter itself is not without weirdness. Because as far as the writing of middle school textbooks is concerned, in terms of number of foreign friends like Rabe, don’t he save more people than Bethune? Why textbooks that are so keen on praising foreign friends say nothing to Rabe Mention-this is worth discussing. There are two reasons for this. One is that Rabe is a Nazi member, which is an identity he can never get rid of; the other is the continuation of a certain Cold War mentality and Cold War logic, because Nanjing is a Kuomintang-controlled area, because Rabe accepted the National Government's medal, so the publication of the previous "Rabe Diary" and the re-development of Rabe today, at this time, is itself a writing act with a post-Cold War flavor.

So "John Rabe" becomes interesting. In my opinion, this film happens to provide a double-sided mirror for the Chinese context. One side reflects certain gaps and changes in Chinese historical writing, and the other side reflects Rabe’s own context in Germany. The meaning of, and then produce referential thinking here. The most striking thing is that in "John Rabe", Rabe’s own Nazi identity is not evasive but strengthened, but it is reversibly strengthened in another interesting way. ——The Nazi party flag, a symbol of evil, can serve as a refuge for innocent civilians. Although Rabe claims to be a Nazi soldier and does not forget to pay the Nazi military salute, it is clear that the film portrays him as an entrepreneur. He initially sheltered civilians, not out of humanitarianism, but only out of the responsibility of "entrepreneurs" to protect employees, but in the end he took on his mission step by step, so he eventually became a hero. So we see that the symbol of Nazi has just been given the opposite meaning visually. Is this a reversal in some sense? Of course this is possible, so the film constantly molested Hitler for political correctness, and arranged a Jewish male second, Rosen (in the order of the film’s cast, in fact, I think that Dr. Wilson is the real male second. No.), through his narration to emphasize the facts of the Holocaust in the film-but the important thing is that in the film, presentation and dialogue through the screen are basically two different things. If it is not an experimental film, usually "seeing is believing" , Then this reversal is actually done: the word "Nazi" cannot be generalized.

So the final strategy of this film became very interesting. The play transferred the evil that should belong to the Nazis, and the massacre was transferred to Japan. Of course, we did not forget to arrange a kind Japanese military officer and assign the ultimate villain to one who was born because of the royal blood. The Japanese prince who is free from trial-this seems to bring out another reflection. Because of the Cold War, Japan's trial of militarism is far more incomplete than that of Germany. However, also because of the Cold War, West Germany's trial of the Nazis was also incomplete, but it was not those who should be tried, but Rabe was tried, so the problem became more complicated. It seems that this issue is not clear in this short article, so I put it aside for the time being. To emphasize one point, the reason for Rabe's trial was "collusion with China" (see end caption). Here, some post-Cold War parameters become more obvious. Therefore, the contradictions in "John Rabe" and the jerky problems in the film can be explained by a possible explanation. To talk about Rabe in the context of the post-Cold War, and to find a balance in the context of Germany, China, and Japan, this is obviously an impossible task. Not to mention the countless places where nationalists may find "feeling hurt", I am afraid that the Japanese side cannot accept this kind of expression. Of course, I can’t judge whether this contradiction is due to the director and screenwriter’s own thinking, or the consideration of the Chinese market and the "Chinese people's sentiment", but obviously it is the Jewish Rosen and the Chinese Langshu who undermine the structure of the film. (The female student played by Zhang Jingchu) is a blunt clue. You can draw a conclusion by simply doing a narrative analysis on this point, so I won’t mention it here.

This is the case on the mirror side, and the mirror side is also quite complicated. Perhaps for Chinese audiences, in addition to identifying with Rabe, they are more often reflecting. When our historical writing is missing for one and other reasons, we can find the other half of the story in this way, itself. It becomes very paradoxical. Although Rabe has become a lonely tragic hero in the film, and although the Chinese face is blurred in this film, the absent elements are exactly what is presented in our historical writing, and the topic is even bigger. Of course, as a film, "John Rabe" is not a history, but a story—I'm just saying that with the reference provided by this film, we may be able to glimpse the problems in our historical writing.

Finally, say a few words "Nanjing! Nanjing! "A Comparative Analysis of "and "John Rabe". This is probably a topic that is difficult to bypass in current and future discussions. . "Nanjing! Nanjing! "Does not bypass Rabe, but Rabe is in "Nanjing!" Nanjing! "It's really vague. Maybe Lu Chuan thinks this is a fact that doesn't need to be explained, but the actual situation is that this fact has been anonymous for a long time. On the other hand, "John Rabe" showed the rape from the front—despite the attempt, the front shows the Ensign Hundred Killing and their game—have to say, even from the crack of the door, this scene is better than "Nanjing! Nanjing! 》More impact. Having said that, "Nanjing! Nanjing! The most impactful scene in "" is about the Chinese soldiers falling down like wheat. Correspondingly, the two episodes of Japanese soldiers shooting and killing prisoners of war in "John Rabe" are similar. "Nanjing! Nanjing! "The problem with "John Rabe" lies in the drama, and the problem with "John Rabe" lies in the drama, but at least "John Rabe" is still a story at all, and there are fewer problems than "Nanjing": if "John Rabe" can Rabe’s dilemma is strengthened, unnecessary clues and characters are deleted, and the play may be smoother, but in view of the previous analysis, if the dilemma of historical expression cannot be solved, the fundamental problem of the play cannot be solved. .

To put it bluntly, "John Rabe" was not intended to film the Nanjing Massacre. For it, Nanjing City is just a scene. Its appeal is to write about Rabe, and then express some kind of thinking. The appeal of this film is not "another ironclad proof of the Nanjing Massacre", but the reflection of the Germans. If someone says "John Rabe" is a commercial film, yes, it is indeed a commercial film, but "Nanjing! Nanjing! "Not an art film either. If someone said "Nanjing! Nanjing! "Because of the deletion, there are probably a lot of deletions in "John Rabe", and it is indeed not smooth in many places. As for "Schindler's List", which will definitely be compared, that is the commercial film and the commercial film. In my opinion, the discussion space of "John Rabe" is a bit larger than that of "Schindler's List" because of the natural particularity of this film in the Chinese context. Of course, the question of the comparison between Tu You and the Nanjing Massacre is another story. The massacre of the Jews is a "human disaster" and the Nanjing Massacre is only "a problem in Sino-Japanese relations." The discourse struggle during this period, the Jewish discourse power, and the position of Western discourse in the Chinese context are all huge problems.

So the conclusion is that for the discussion of the Nanjing Massacre, a high-grossing commercial film in an international context may be more effective than ten academic works, as long as it can provide space for topics and reflections. A post-reading writing method would be that this movie tells us that when a person faces power, he can make some great choices; an advertising writing method would be, "John Rabe" is "Chinese version of Xin Dele’s list, the reviews from all countries are unanimously appreciated" (see the cinema advertisement); a critical way of writing is that "John Rabe" shows a certain reflection in self-contradiction-but these are conclusions, to me , This is a text with the nature of the starting point for discussion and thinking. Entering from here is more reading and more referential speaking possibilities.

View more about John Rabe reviews