If you only pay attention to those people who have sex with each other, two generations of incest, etc., and think that the continuation of race depends on the driving force of sex, then it is inevitable that one-sidedness will inevitably lead to continuity with sex? People can throw their newborn babies in the fields for their own survival, that is, completely leave the survival of the race to the decision of nature, and voluntarily equate themselves with animals. Some animals are more "kind" than people, but they only teach their children some survival skills. After they grow up, they have nothing to do with each other. Of course, animals do not care whether their children or their brothers are stupid, whether there are women, or not. Will not have a relationship with someone for the last words of a loved one.

Knowing how to sacrifice individuals for the continuation of the race, talents begin to be humans.

Mother-in-law Azhen is like this, the order of the family and the continuation of the family are all her beliefs, which gives her an extremely powerful will and the power to despise death. From killing his father to understanding his father's emotions, Chenping finally carried his mother up the mountain and agreed with his mother's actions. This is the most true portrayal of the ascent of the human soul. No matter how difficult the climb is, how much we love sex, life, and our relatives, our spirituality as humans will guide us to surpass all of this and finally become a god who is not afraid of death. We all know that there is no Narayama god. The real Narayama god is the mother-in-law Azhen, who is dressed in white snow. The unique self-sacrifice spirit she represents protects the villagers from multiplying for generations. (The film utters this meaning directly through the fool————The fool is afraid of snoring with the old woman who slept with him, so he took out Granny Azhen’s teeth and put them in her ears as amulets)

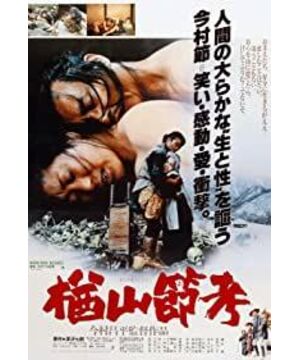

Let’s talk about the Imamura version and the Kinoshita Keisuke version. :

I saw an online commentary on Imamura Shohei's film called "

Masahira Imamura drew too much from Keisuke Kinoshita's version, from the exterior scene—the arrangement of thatched houses and the background of the forest; to the interior—the indoor equipment and furnishings, and even multiple lens framing, all borrowed from the Kinoshita version. Especially in the end, the artistic conception of Azhen's mother-in-law wearing snow created by Kinoshita's version is completely inherited by Imamura's version. But looking at the whole film, there is a very fundamental difference between the two.

Keisuke Kinoshita's version is very classical and simple, praising humanity and the greatness of women. The most interesting thing is the end of the film. A train goes to the mountains. This treatment is so simple and cute. It is a bit like the scene of the success of the revolution after the sacrifice of heroes in Chinese movies. The ending of the film is the only real scene, expressing Kinoshita's idea that society will develop and we will eventually get rid of ignorance and poverty.

Let’s compare the version of Imamura Shohei. I noticed that there was a plot in the Kinoshita version, but the Imamura version was deleted: Tatsuhira ran home with his blood-filled mother on his back, and when he entered the house, he saw his new wife who was eating white rice. Excited with emotion, cursing this poor environment. In other words, in the Kinoshita version, "poverty" comes from the protagonist's own perspective. Masahei Imamura didn't want to express "poverty" deliberately. In Imamura's version, there are no lyrics outside the painting, only the characters themselves muttering folk songs. In this enclosed mountain, there is no outside perspective at all, so the villagers don’t understand what “poverty” means. “Poverty” comes from our audience. For the villagers themselves, there is only a primitive established state of life. Everyone is the same. If there is no relative "rich", there is no relative "poor". If it is not "poverty" that causes the greatest suffering, what is the greatest suffering? You can't die well. Look at what the dying old woman (the one who later satisfied the idiot’s desires) said to the old woman: she didn’t want to die in the village, she wanted to die on Nara Mountain; look at Ayou’s father’s greed and fear, contrast with Azhen Mother-in-law's calm. We understand how different the death of humans is from the death of animals.

Therefore, Imamura’s “horror” does not come from the real natural environment, nor from the realistic expression of “animality”, but because he pressed humanity. He no longer put the blame on the environment, but confronted the humanity. The despicable and noble, this way is indeed very modern.

The two versions are often controversial in the handling of one plot: Ayou pushed his father off the cliff, did Chenping fight with Ayou because of this. The two editions naturally have their own reasons.

The imamura edition emphasizes the similarity between the two generations. Tatsuhira is like his father. Asong and her parents like to steal things. From here, I guess Ayou's father must not be a dutiful son when he was young. The inhuman son, when Ah is old again, will certainly bear more fear of death because of selfishness. As a father-killer, Tatsupei, looking at Ah Yu who also killed his father, how complicated should it be?

In the Muxia edition, Ah You's father's greedy life Jane has lost his shame, and it is conceivable that he died with no dignity in the end. And Chenping and Ah scuffled again, undoubtedly venting self-blame and pain on others. Of course, from the perspective of audience identification, we can also understand this practice of punishing evil and promoting good.

Finally, as a non-Japanese audience, from the Kinoshita edition, I approached a traditional Japanese world with sound (strings and lyrics) and color (singing and dancing, scenes), and rich in humanity. From the Imamura edition, we see a kind of modern people’s speculation without borders. I haven’t seen such a successful reinterpreted movie for a long time. Let’s ask if we read the original book and then make another film after reading the old edition. Reinfuse so much of your own spirit? Learning Imamura is a way out for modern directors.

View more about The Ballad of Narayama reviews