I have never liked to write film reviews with an analytical attitude, because I think reading film reviews is no substitute for watching films. Film critics are only responsible for picking out some highlights from the film and doing some philosophical thinking on them. Therefore, I don't like to write all the details when writing a film review. Many less important details will naturally be seen when the audience goes to see it themselves, and there is no need for film critics to stifle their imagination. I prefer to think about and write where I want to, and when I have something to say, I will improvise a high-level speech, and I will not force it when I have nothing to say. Film reviews written in this way may seem very "subjective", but I think reading other people's reviews is a kind of thinking about intersubjectivity. A good film review can surprise people and make people interpret more things, rather than fix one. what is.

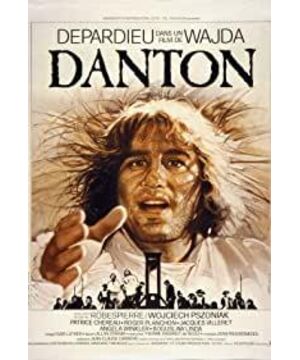

I have watched this "Dandong" by Polish director Vajda about three or four times. I watched it repeatedly, not because of how good the film is, but because I am addicted to the historical figures of the Legal Revolution, and there are not many literary and artistic works depicting this historical period on the market. Wajda's artistic expression in "Dandong" is always full of tension, but the theme of "Dandong" is actually a commonplace in the eyes of today's people. "Dandong" is nothing more than a film that borrows the past to satirize the present, using France under Robespierre as a metaphor for Poland in the era of Wajda, so as to explore the nature of totalitarian politics. Compared with similar films such as "Goodbye Lenin", "Dandong"'s exploration of totalitarian politics is actually not that profound. "Dandon" depicts a very classic totalitarian world: a dictator with an ascetic image (Robespierre), a society under political pressure, a society full of rebelliousness, a rebellious alien who opposes the dictator seer. The secret police smashed the newspapers, the dictator used superb sophistry to confuse black and white, the "democratically elected" National Convention was like a display under the monitoring and manipulation of Robespierre and the Public Security Committee; Robespierre's political enemies Danton and Demu Lan slammed his politics of terror, calling for free speech and justice. In the end, Danton and Desmoulins still lost to Robespierre's power and were sent to the guillotine to be executed, but Robespierre himself couldn't help but realize that the totalitarian revolution would eventually lead to an irreversible trend. collapse.

"Dandong" is far from unique. Movies like "Goodbye Lenin," "The Tin Drum," and "Dad Going on a Business Trip" have successfully portrayed a society under totalitarian repression, and the mental state of people in this society. However, the exploration of the nature of totalitarianism in these similar films, including the reflection on their specific historical period, is more complex and profound than that of "Dandong". The opposition set by Vajda in "Dantong" is obvious: Robespierre is abstinent and inhuman, and is good at using sophisticated words and complex theories to secretly exchange concepts, confusing black and white; Dandong is indulgent, vulgar, flesh-and-blood, and straightforward. White is succinct, full of true feelings and universally established moral truths. We have seen too many such routines now, and it is nothing more than criticizing the hypocrisy of totalitarian politics and exposing its distortion and trampling on human nature and truth. It's easy for Robespierre fans to criticize the film, Wajda clearly "dehumanizes" the character of Robespierre, establishing him as an other, an enemy of the people, horror The embodiment of politics, the walking guillotine. At the beginning of the film, Dandong, who was returning to Paris, saw the sinister guillotine in the heavy rain, and then the camera turned to Robespierre, who was sickly couch with a pale face. The significance of this shot is self-evident. Dandong returned to Paris, facing the guillotine, the high pressure of the terrorist government, and Robespierre behind this government.

If Wajda merely struggled to portray an ascetic, inhuman, cold-blooded dictator versus an indulgent and thus "flesh-and-blood" rebel, the film would be vulgar at its core. The abstinence in Robespierre's stereotype is often emphasized as a sign of his inhumanity, while Danton's indulgence and corruption are regarded as the proof of his humanity. This makes us question whether a dictator must be ascetic, inhuman, alienated enough to become a clearly distinguishable other, and whether sensuality must be equated with genuine human nature. Danton and Robespierre in history are nothing more than two politicians. Robespierre likes abstinence, Danton indulges in sensuality, Danton criticizes Robespierre for being inhumane, and it is nothing more than personal taste and Robespierre. You can't match the number, and the second is to use the personal style of political opponents to attack and distort Robespierre's public image. In the eyes of the incorrupt Robespierre, Dandong's indulgence and corruption represent the degeneration of his personality. Dandong is a political speculator with corrupt morals and a public enemy of the people who harms the country and revolution. In the eyes of hedonistic Danton, Robespierre's abstinence reflects his hypocrisy and inhumanity. Robespierre is not only alienated from the people, but also lacks the most basic humanity. Robespierre thinks Danton is immoral, Danton thinks Robespierre is not a person, and they both think that the other side is the enemy of the people. From an objective point of view, a personal style is a personal style, which is not necessarily related to a person's governing ability and ideological level. Whether the Dandong Party, Robespierre and the Public Security Committee, or the government after Thermidor, in the end were unable to maintain a stable and strong government, let alone solve the problem of food for the French people - triggering the French Revolution the original reason. In the end, it was Napoleon who had to introduce a warrior to clean up the mess for this group of politicians indulging in intrigue.

However, apart from the film's rather good lens language, cool lighting techniques and depressing background music, Robespierre's psychological undercurrent throughout the film is also a highlight of the film. Contrary to his ruthless, iron-fisted revolutionary image, Robespierre has been anxious, hesitant and thoughtful throughout. While emphasizing Robespierre's inhuman image, the director also emphasizes the contradiction between his indifferent appearance and his actual inner activity. As a stage actor, Vojesic shows this tension very well. Compared with St. Just's frenzy and the insistence of the Public Security Committee, Robespierre has been hesitant. At the beginning, when Saint-Just tried to persuade Robespierre to execute Danton, Robespierre did not agree. Later, when the Public Security Committee first discussed the purge of the Dandong faction, Robespierre first pondered, then expressed hesitation. Some people may interpret the ambiguity of Robespierre's attitude as his hypocrisy, but I think Robespierre is indeed hesitant. Wajda's Robespierre is not just a stereotypical image of a dictator, he is also an embodiment of revolutionary contradictions, fanaticism and anxiety. The occasional high fever of the Incorruptible not only reflects his tormented state of mind, but also symbolizes that the revolution has entered a fever-like period. The secret conversation between Robespierre and Danton reflects both the antagonism between the two politicians and the breakdown of their relationship, as well as the psychological antagonism beneath Robespierre's cool exterior. Robespierre, who was questioned by the drunk Danton, seemed to be silent, but in fact seemed to be under torture. After this negotiation broke down, Robespierre no longer hesitated, and for a long time, we couldn't "see" what Robespierre thought - until the end, when he was nervous in bed again Awakened (he did the same at the beginning of the film, awakened in his dark little room), and spoke to the audience a bizarre speech that seemed like a prophecy.

Robespierre's words at the end are the best part of the film. When we saw the guillotine cut off Danton's head, Robespierre covered his sickly pale face with a white sheet, like a dying man, covering himself with a white cloth covering his face with a corpse. . Saint-Just walked in with a smile on his face, as tough and fanatical as the beginning of the film - the cold and cruel Saint-Just like the death behind Robespierre, opened a pair of "horror" Black wings shrouded his revolutionary mentor and the ghostly capital of Paris. (Some people criticize the film's St. Just as unhistorical, and vilify and distort his real image, but these people also ignore the symbolic meaning of St. Just in this film.) "You must be a dictator now. It's over." Saint-Just said to Robespierre with a smile, his icy blue eyes and his qualitative tone were unquestionable, as if the judge of the underworld was reading the verdict. Robespierre lifted the white cloth, revealing a corpse-like face, "I feel... everything I believed in and lived for has collapsed forever," he said. "The revolution... went the wrong way." He suddenly looked at the camera, his eyes helpless and panic. Then Robespierre stared at the camera - he looked directly at the viewer, as if he had left the historical period in which he was in the film, and instead of the director, he said to the viewer: "You see now that a dictatorship has become a necessity, the nation can't govern itself, democracy is only an illusion." In this shot, Robespierre is like a Delphi priestess (Pythia) suddenly possessed by ghosts, transcending the mundane time, to his bed Shengju next to him and the audience two hundred years later outside the camera conveyed an oracle. The final scene is fixed on Eleonore's younger brother's face. The boy recites the "Declaration of Human Rights" to the camera with an expressionless face. The camera zooms in a little bit to close up his face. At the end, the innocent face of the boy is the same as chanting scriptures Ended in the recitation of the boy, until the boy's face and voice also disappeared in the gradually enlarged halo and murmur.

If Wajda's Robespierre is a Macbeth-esque tragic antihero, and Danton is a Robespierre-Macbeth-esque dark psychological tragedy, this eerie scene is also reminiscent of Macbeth's tragic antihero. A scene from White. Towards the end, Macbeth, who was besieging the city, said this monologue after learning that his wife had committed suicide:

She should have died hereafter; There would have been a time for such a word. To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow, Creeps in this petty pace from day to day To the last syllable of recorded time, And all our yesterdays have lighted fools The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle! Life's but a walking shadow, a poor player That struts and frets his hour upon the stage And then is heard no more: it is a tale Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, Signifying nothing.

Macbeth in this monologue is like Robespierre in the prophetic lens, which suddenly jumps out of the historical time in the text and talks directly to the viewer. They are at the same time the puppets and prophets of their time.

[1] The title of this article comes from a speech by Robespierre himself in history.

View more about Danton reviews