By Owen Gleiberman (Variety)

Translator: csh

The translation was first published in "Iris"

Now, those pieces are finally put together into a whole. So, how does it look?

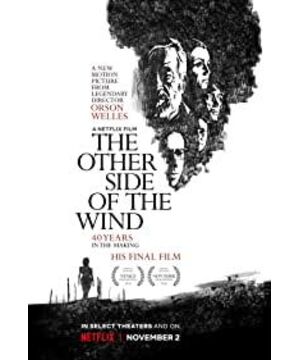

"The Other Side of the Wind" tells the story of a legendary Hollywood director named Jack Hannaford (John Huston), who is trying to finish his latest project. Now that it has taken us forty years to piece together the fragments of Orson Welles' posthumous works into what can be described as a complete "movie", the first question we have to ask is: in the eyes of the audience, what is it? Does it look like a coherent film?

The answer is (basically) yes. Diligent archivists and technicians worked hard to make "The Other Side of the Wind" complete. The restoration team, led by Oscar-winning editor Bob Murawski ("The Hurt Locker"), worked on a hundred hours of film left by Welles (including his extant notes).

All of this is like a holy movie archaeological excavation program. What they've done is an eerie, rather tumultuous, delightful film that's easy to spot in Orson Welles' style. From that flashy and dark atmosphere, you can feel the high concentration of "Wells gene". So is it a good movie, or a bad movie? A fascinating mess, or a serious story? A work of art, or an antique? It can be said that it has something to do with each of the above.

"The Other Side of the Wind" has a lot of characters (even if many just pop into the camera and blurt out a line or two). It has a loose structure, but step by step, it slides into darkness. It also creates a mellow, languid vibe that captures the rotten core of Hollywood.

It also presents a chaotic, bewildering array of fragments, using a variety of different films (including 35mm and 16mm, black and white and color). The film was made piecemeal by Wells between 1970 and 1976, and he was not able to finish it before his death. However, this does not fully explain the general, intimate, dreamlike character of the film. There are some signs that, even if Welles were to finish the film, it would still be highly generalized, deeply private, and dreamlike.

Wells was fifty-five years old when he returned from Europe to start the project. He initially envisioned the film as a "return," and he clearly meant a masterpiece -- Welles' great manifesto involving Hollywood, the media, the new teen culture, and twisted cinema. politics.

Still, the project was carried out in the style of Welles' late career shooting. It was a dreamer, low-budget shoot with the slogan "I make movies at home as fast as I can on the road" (for example, "The Fake" and "Don Quixote"). This "self-sufficient" aesthetic is based on a vision, or rather a paranoid illusion: Wells, a director mutilated by the Hollywood studio system, shoots the final film himself outside the system.

But when we watched those final films, the thought that stirred in our minds was this: If he didn't have the budget and crew, if he didn't have a production company behind him, would he be able to do his own thing when he was making a movie? Sophisticated craftsmanship - camera angles, sharp lines, point of view shots? In other words, can he show us a magical, Orson Welles-esque movie?

Such a movie is indeed a fascinating dream. But it's hard not to suspect that a big reason Orson Welles didn't finish The Other Side of the Wind was that he didn't want to do it at all. For him, the alchemy-like process of making a film is more sacred than the finished film itself. "Never Finish the Movie" is a pretentious, self-destructive, Wellesian move.

He told us that Hollywood makes movie products, and his passion for making movies goes beyond that. Pure process is everything. "The Other Side of the Wind" is a highly independent, art-made, "I am the camera" type of film. Put together its shattered images, it's an absurd tale, a comedic take on Hollywood luxury and a fascinating case of Hollywood's critical illness. For Wells, Hollywood is a dream factory that doesn't let you tell the truth. "The Other Side of the Wind" is a reversal nightmare in an unknown place, turning reality into a precarious mirage.

When the film first started, we felt like we were watching a sketch of the film, not the actual "movie". The first twenty minutes are restless and confusing; the film keeps throwing out new characters and new lines, and we don't see anything that could be called an "event." It's as if Wells never learned how to take a shot—it could be a stylistic choice, or it could just be the result of a rush. But even so, "The Other Side of the Wind" does more than just document its charming and quirky filming.

At the beginning of the film, several actors suddenly appear in front of you. Peter Bogdanovich in particular stands out, playing Brooks Outlake, the sophisticated film "Master," beloved by Hannaford for his oily tone. In this film, a documentary about Hannaford is being filmed, and everywhere you go there are people with cameras. This is the beginning of what Wells refers to as the "media age of the 1970s"—but now it looks like he's heralding the age of the iPhone.

For a long time, "The Other Side of the Wind" didn't feel like a story, right down to that desert farmhouse scene. All gathered to celebrate Jack's seventieth birthday. His close friends, admirers, and admirers are there, even some of his enemies, such as a film critic (Susan Strasberg) who never gets along with him.

We also see some of Welles' young directorial partners, like Paul Mazursky and Henri Jaglow, sitting around arguing about class struggle. After a while, John Huston squinted slyly around (reminiscent of his memorable performance in "Chinatown") and stepped into the dramatic spotlight.

Is Houston playing a portrait of Wells himself? Yes and no. Hannaford is as old as the movie itself, from the silent era of Hollywood, and knows all its dirty secrets—some of his own. As a director, he's a "man of men," a Hemingway/Hawks-esque figure who can shout things like, "I think it's easy to make a good movie. I don't mean to make a great one. movies - that's another thing" or "it's okay to borrow from each other, as long as we don't borrow from ourselves".

In a way, Hannaford is Hollywood's power elite. Wells has never experienced that privilege since Citizen Kane. But Hannaford is also a remnant of a bygone era. Gone is the studio system that let Hannaford create his legend, and the new Hollywood—perhaps the last Hollywood—still hangs in the balance.

So did Welles, who had just returned from exile in Europe, but the film he was trying to accomplish had to be Wellesian. This is a bottle of contrived hallucinogens, this is an escapist "pretend to be tender" movie, this is "The Other Side of the Wind". We've seen too many scenes like this - it begins in the screening room, where Hannaford's skinny sidekick, Billy Boyle (Norman Foster), tries to sell the movie to potential Investor (Geoffrey Lamb), but that investor leaves the show halfway through.

It's hard to blame him. Wells is using this "movie within a movie" to satirize Antonioni-style youth films. It begins like a sequel to Zabriskie Point: John Dyer (Bob Langdon), the Jim Morrison-esque protagonist, stands lazily in a barren land, facing the woman The protagonist (played by Wells' mistress), a sultry, Oya Kodak-like woman, is in a state of semi-nudeness.

Later, when Jack screened the film at a party, we saw more footage, and it became a bohemian, utterly evil thriller. It's hard to speculate on Wells' intentions here, though. We can laugh at some of the scenes, but most of them are somber and sluggish.

If this is Welles' prediction of the New Hollywood, it looks both hip and (in our hindsight) outdated. Even more intriguing is Jack's party itself, which appears to be a boozy orgy and innuendo allegory. The dialogue in "The Other Side of the Wind" is like a vicious cold wave.

"Jack's journey has been reconciliation after reconciliation." "This guy is parasitized by his followers." "Mr. Hannaford likes to pretend to be ignorant." "He can put a mere bad The idea has become something truly vicious." "If you want to fight him, please invite me." If the slander is a matter of words, then the audio-visual style of this film is also strange. It builds on the high-speed filming techniques Welles had used in The Fake, creating a hypnotic multimedia shot ahead of Oliver Stone's Natural Born Killers.

We can't help but imagine what Stone would have thought if he looked at this forty-two minute segment of Welles' "assembly." The jump from black and white to color doesn't just give us a sense of imbalance. It invites us to observe the characters in the film as if we were observing the crawler in the cage. The supreme joy of watching "The Other Side of the Wind" is mainly because the film is so "wells". The film feels the most like Gone with the Wind (to me, Welles' greatest film other than Citizen Kane).

It even has a bit of a "rosebud" meaning - Hannaford has a covert homosexuality, as we can detect in his elusive relationship with John Dyer ("When Jack found him, he still selling vacuum cleaners”). In this film, this gay complex is not just presented as "gossip", it is Welles' metaphor for the hypocrisy of Hollywood - the manly director who shaped his own image, created He made his films, but it was all based on his self-deception. From a psychoanalytic point of view, this is also the fundamental reason why he did not finish the film.

In all fairness, though: "Gone with the Wind" and "Citizen Kane" are by no means the same art as this film. "The Other Side of the Wind" is so coherent, so compelling. The result of the restoration team has restored this collage-style film, so that we no longer have to speculate on its appearance. You might be wondering what The Other Side of the Wind would have looked like if Welles had been working on the film from the start of his career and given it the mass production it deserved. But, in a way, you no longer have to worry about the movie being locked in his brain forever.

View more about The Other Side of the Wind reviews