This article is translated from Pasolini's "Life Trilogy" CC Blu-ray set booklet. Out of my love for Pasolini, I was surprised by his candid and unabashed attitude towards "sex" in the "Trilogy of Life", which makes people feel natural and beautiful, but does not generate pornographic thoughts. Bertolucci's "Stealing Incense" once gave me a similar feeling. English university level 6, please forgive me for translation errors.

The following is a transcription of Pasolini's Q&A at the 1972 Berlin Film Festival's Canterbury Tales press conference. The launch was covered in Italian, English, German, and translated into French in the February 1973 issue of "Jenue cinema". This article was translated from French by Alexandre Mailon.

ask:

(1) At the end of the movie, we see Chaucer's shenanigans, followed by Chaucer - Pasolini's face (Annotation: Pasolini plays Chaucer himself in this film), the pilgrimage to Canterbury Cathedral The line, and finally Chaucer's smile. Is this a satire of human nature or pity?

(2) Why is St. Paul quoted in the brothel scene? (Annotation: "1 Corinthians" 6:13 "The food is for the belly, and the belly is for food; but God will destroy both. The body is not for fornication, but for the Lord; and the Lord is for the body. ”, the movie quotes the first half of the sentence about food)

(3) Some characters, such as the buyers in the mill, behave very naturally, while others behave strangely. Why?

(4) Some of the dialogue in the film is spoken in the Bergamo dialect, are you trying to make an analogy to the English dialect? (Annotation: The film is available in both Italian and English. The Italian version was shown at the Berlin Film Festival, and the English version has not yet been produced)

Pierre Paolo Pasolini:

It would take a long time to answer these questions one by one, so I want to answer them as a whole.

I shoot these films for the pleasure of narrative. Narrative pleasure refers to the pleasure of telling a story. It means creative freedom in relation to story material. This material-related freedom requires that all Chaucerian reconstructions must be visual, rather than reconstructing the world of that historical era as it is. "History" is only a point of view in this film. I had to "forget" Chaucer in order to visualize the film, which is my job as a director.

My personal psychological attitude towards the characters and facts in the film is a mixture of irony and pity. Irony and pity check and complement each other until the finale: first the irony about hell full of demons, then finally "Amen," which justifies the ironic violence about hell.

Regarding those two specific questions:

Regarding the citations of St. Paul, all my texts are either direct quotes or adapted from Chaucer. That quote already exists in Chaucer's novel. As for the presence of the Bergamo dialect - or the Fleur dialect - in the film, it is indeed an analogy to the English version. They did not speak Old Vic English, or the English popular among the bourgeoisie, but English of all classes. So in the penultimate story (the table of death), the three Scottish boys who meet by chance and live in London speak not Scottish dialect, but English with a Scottish accent.

ask:

(1) Chaucer gives continuity to the whole story by showing the way the pilgrims tell it. But in the film, there is no obvious connection between the story and the story, which may confuse the audience. Why did you choose to do this?

(2) What do you think of the character Chaucer?

Pasolini:

I actually shot the pilgrims telling the story... I then removed those inter-acts and kept those parts of the film without success. In Chaucer, this treatment gives the feeling of a book in a book, but in the film it seems mechanical and rigid. This is a major correction I made to the film.

I have to say, as a director, the main problem with this film for me is its structure. I don't know why the first story is placed first and not seventh, or why the seventh story is not first or third. The material has its own expectations, and all I have to do is understand and follow that expectation in the editing room. I had to guess what the structure and pacing itself required when choosing a story.

As for Chaucer in the film, it is a completely arbitrary and symbolic figure.

This film, as I always say, is metalinguistic in a way. It's a movie about a movie, a conscious movie. It ends up being a consciously mixed game of sarcasm and pity. Chaucer appears as a casual character in order to bring out the meta-linguistic feel of the film.

ask:

(1) You said that all the exterior parts of the film were shot in the UK, but what about the interiors? Are the film crew all British?

(2) How long did it take you to make this film?

(3) Did this movie bring you the same pleasure as "Ten Day Talk"?

Pasolini:

The film was shot entirely in the UK, not just on locations. All are British, except for the last hell scene, which I filmed on Mount Etna.

I spent 9 weeks shooting.

As for the comparison between this film and "Ten Day Talk", I will have to wait until the English version comes out before I can decide which one I like better.

ask:

Is there a line between eroticism and pornography?

Pierre Paolo Pasolini:

Let me expand the scope of this question a bit... What's the difference between Eros-eroticism and porn? Sexual instinct is a wonderful thing. According to Freud's insightful interpretation, the sexual instinct is one of the two basic elements of life - the sexual instinct and the tendency to die (Eros and Thanatos). Sexual orientation is a sociological, aesthetic, intellectual way of expressing sexual instincts. So it rightfully has a right to be a part of our lives. Pornography, on the contrary, is the result of a vulgar social sexual exploitation of the sexual instinct. I have no intention of condemning porn because everyone has the right to porn, it's their business. This is too bad. But sexual orientation is a wonderful thing, and porn is like a byproduct of it.

ask:

Based on the opinions of workshops held in Helsinki and Moscow, Pasolini, who we highly praised for his courage and intelligence, would have been better off by the audience if he had toned down the morbid erotic tendencies of his films. to accept? Is it necessary to arrange so many pornographic scenes in the movie?

Pasolini:

Miss, I know there have been endless seminars going on everywhere since the Counter Reformation. I had to completely ignore their opinions.

I wish to discuss my problem rationally. As I have explained, my films are mainly based on style, a style that is fantastic and visual, and therefore expressive. Expressions of violence have causes and objects. So I can't just exclude myself from filming sex scenes. If I picture a green leaf as greener than it really is, it's because I'm seduced by expressionism and extreme expressiveness. Just as I paint a leaf greener and make the faces of the actors I choose more vivid, I can't resist stylized violence in sex scenes alone. I did all of this out of style...but it turned out that what I ended up showing was neither vulgar nor erotic.

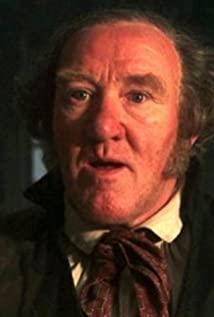

(The film actor, British) Hugh Griffith:

(Translator unintelligible for opening remarks) I started speaking in my native language, then in Welsh, a language people used before the Anglo-Saxons "made this country better". My language is also the way Chaucer started his story...but I want to know before you ask Mr. Pasolini a question, has any of you read Chaucer's original text?

The reporter replied:

I think very few people read Chaucer, even in England. Probably some small groups in colleges will read it. But there is a big difference between reading Chaucer in small circles and showing Chaucer's story in front of millions.

Pasolini:

I would like to talk about this issue. These linguistic issues are very close to me. The reason why I chose to shoot "Ten Days", "Canterbury Tales", "1001 Nights" is precisely because they are all literary works from their own language, so when adapting them, language (barrier) issues must be Receive attention. I try to solve this problem in a poetic way. All of the dialogue in the Decameron is spoken in the Neapolitan dialect; in other words, an ancient, strange, and incomprehensible language for Italians from other regions. I hope the same is true for The Canterbury Tales. Its dialogue is not in modern English, not in Old Vic English, but in real English - even in situations that Britons themselves find it difficult to understand, whether due to the Scottish accent in the film or London accent.

ask:

Last year, you said you were approaching a stage where you were about to retire from the film industry, are you entering the final stage now?

Pasolini:

Regarding the retirement you mentioned, my decision has not changed much so far. I am no longer young and have no illusions. But I still want to keep fighting.

(Finish)

View more about The Canterbury Tales reviews