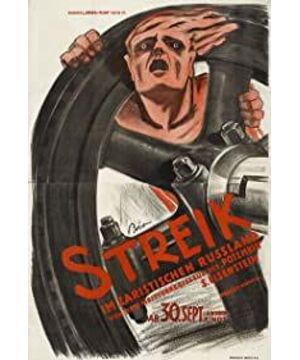

Eisenstein's film collective The Iron Five was founded in 1923. Its members are: G.V. Alexandro (GVAlexandrov), M.M. Strauch (MMShtraukh), A.I. Levishin (AILevshin), M.I. Gmorov ( MIGomorov), A·A·Antonov (AAAntonov). In his first theoretical work, Eisenstein suggested using montages to connect various dazzling elements in lieu of the plot of a movie. In his first feature-length film, The Strike (Stachka, 1925), he pushed the masses into the hero's place, replacing the stars of pre-revolutionary Russian films as well as contemporary Western systems. For Eisenstein, the picture itself is a montage unit with independent meaning, an "attraction"—that is, some kind of shock to the viewer's perception. So, a "montage of dazzling things" is a series of shocks that have such an effect on the audience -- motivating the audience to respond in such a creatively productive way that the audience becomes the director's collaborator, creating the film text. Here is a completely different place between Eisenstein and Kurishov, that is, Kurishov regards the audience as passive, as if it is just a container for receiving prepared information. For Kurishov, each picture in the montage functions like a letter in a word, not the content of each picture itself has any special meaning, but the combination of these pictures creates new meanings... At the age of twenty-five, Eisenstein was already a daring and difficult figure in Soviet theatre, and his "The Wiseman", considered a classic revival of Ostrovsky The irreverent, circus-style adaptation of the work marked a high point in post-revolutionary Soviet theatrical achievement. After two more plays, Eisenstein was invited by the "Proletkult" organization to make a film. Thus came The Strike (1925), from which the Meyerhold apprentice became the most famous director in the Soviet Union. "The pickup smashed into pieces," he wrote years later, "and the driver fell into the movie theater."

Eisenstein brought everything he learned in the theater into the film. His Soviet typage rests on the depsychologized personifications he finds in the commedia dell'arte. His later films brazenly resorted to stylized lighting, costumes and backgrounds. After all, Eisenstein's notions of an expressive movement, exceeding norms of realism, and eliciting outright excitement in audiences, appear time and time again in his films. In "Strike," a whistle-like whistle blown by the workers as they fight the foreman becomes a sort of calisthenics exercise.

View more about Stachka reviews