Press: When discussing labor relations and the aesthetic ideology of the proletariat from the perspective of video, we must not be able to bypass Eisenstein as a key starting point. As the founder of the montage technique, Eisenstein became one of the leaders of the Soviet avant-garde with his revolutionary artistic language combined with clear political ideas. As viewers today, how should we dismantle the organic combination between image form and political ideas? As a creator in the historical wave at that time, what breakthroughs did Eisenstein achieve and what problems did he touch? To this end, we selected this article written by Philip Rosen, an emeritus professor of film theory and cultural history at Brown University in the United States, to pave the way for the discussion of the film and explore Eisenstein from a broader academic perspective. Stranded generation of montages in works.

Eisenstein's late film theory: Utopian viewing behavior and aesthetic collectiveness

Author | Philip Rosen

Translator | Ding Xu and Huang Xiaoqian

English title: Eisenstein's Later Film Theory: Utopian Spectatorship and Aesthetic Collectivity

The number of words in this article is 8964 words, and it takes 20 minutes to read.

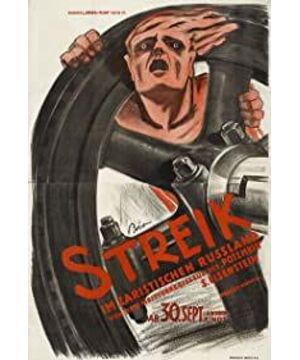

Although we are going to discuss Eisenstein's general aesthetic problems in the 1930s and 1940s, we must start from an earlier time. Sergey Eisenstein made four silent film appearances between 1925 and 1929 and made world cinema sensations. His work was immediately hailed by many in the Soviet Union and outside the Soviet Union (including himself) as a revolution in aesthetics and politics. It was also during these years that he started a trend of creating theoretical articles and essays, promoting his methods and unique ideas about cinema, which was still a new medium at the time, among the politicized Soviet avant-garde. Several works written by Eisenstein in the 1920s are now regarded as milestones in the history of film theory and as milestones in the history of several Marxist concepts of film, popular art, and modernity. text.

As we all know, the 30s will be different compared to the 20s. Most of the avant-garde art was suppressed as the socialist realist aesthetic was officially recognized by the Soviet Union. Eisenstein was also the subject of criticism due to his reputation, and several of his film projects were not licensed. He was in danger for a while, but starting with the release of "Alexander Nevsky" in 1938, he began to receive government support on and off. He persisted in writing theories throughout those years, which was the most important at the time. Until his death in 1948, in addition to the classic papers completed in the 1920s, Eisenstein produced thousands of pages of theoretical works, most of which were not published publicly. These later theoretical works include complete manuscripts of at least two important books—Nature Not Indifferent and Montage—now published, on the content of a third book, The Method, and Lots of papers and notes. In 1942, several chapters from the book on montage were consolidated into a book published in English under the title The Film Sense. In 1949, several important chapters from "Nature Not Indifferent" were included in the English edition of "Film Form", a chronological catalogue that traced him for 25 years. trajectories of film theory.

In this article, I will refer to the English version of Eisenstein's theoretical works. The most important theoretical source is Eisenstein's three-volume collection (SM Eisenstein: Selected Works), edited by Richard Taylor and published by the British Film Institute and Indiana University Press (BFI and Indiana University Press) Published - Volume 1: Writings 19221924, trans. by Richard Taylor, 1988; Volume 2: Towards a Theory of Montage, trans. by Michael Glenny, co ed. by Michael Glenny, 1991; Volume 3: Writings 19341947, trans. by William Powell, 1996. However, more theories are derived from his unpublished papers such as Non Indifferent Nature, trans. by Herbert Marshall, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Many readers see the available fragmented later work of Eisenstein as a negation of his famous earlier theoretical work, and as a tactic rather than a true theoretical development— — As someone put it in 1942, he saw Eisenstein's later theory as an attempt to "adopt the official Stalinist culture as an umbrella". Since then, academic discussions have revolved around questions such as: Are there really two Eisensteins, and are they really different in the early and late periods? If not, how did the change happen? Given the pressures of Stalinism, how does Eisenstein unfold the narrative as a Marxist theorist in his writings (especially in his later writings)?

Today, we have access to many of his later works. Some of the same issues may arise, but the seriousness and complexity of his later works, their breadth and depth both philosophically and historically, and the long-term cultural engagement they display are unquestionable. Given the vast amount of Eisenstein's previously unpublished literature now available, contemporary film theorists such as Jacques Ormont and Geoffrey Norville-Smith call it "one of the great philosophers of art of the 20th century" or even "The Most Important Aesthetician of the 20th Century", etc. Thus, by deciphering a utopian element in his concerns, the question I want to explore is: How did Eisenstein's primary concern become the concern of Marxists at the time? This article will focus on several cases from Eisenstein's work that run through his early and later works and highlight the issues that concern him most. During Eisenstein's life, one of the theoretical issues he was most concerned with was film and aesthetic form, which in turn often involved the audience, the reader, or, in film theory, the spectator. To discuss form and the beholder is to understand how to "articulate a film or a work of art to the audience."

We know that Eisenstein began to really focus on the theory of form with the help of the term montage. He has used the concept of montage throughout his theoretical writings and has extended it. In his work in the 1920s, the concept of montage soon moved beyond the confines of film editing to mean a whole dialectics. It means that all the different elements of a work are confronted with conflicts and contradictions with other elements, but are ultimately resolved in a dynamic dialectical system. Furthermore, he sees montage in this sense as a work on and with the beholder.

He proposed this framework in Marxist terms in his earliest theories, three years before his famous 1925 essay. Eisenstein had just finished his first film, The Strike (which is now very famous), in which he tells the climax of the strike. The film uses a sophisticated montage technique to alternate between footage of Russian Cossacks slaughtering strikers and documentary footage of bull slaughter in a modern slaughterhouse. Eisenstein defined such montages as a formal mechanism, but he used Pavlov's newer terminology of conditioned reflexes and unconditioned reflexes to describe the importance of complex montages sex. Cinema, he explained, arranges stimuli and conflicts that integrate the viewer's previous conditioning into desirable ideological new ways. However, Eisenstein also recorded some failures: he asserted that only bourgeois audiences would be properly shocked by the climax of the strike, not workers and peasants. He believes the reason for this is that workers associate bull slaughtering with the daily labor of meat processing, while farmers associate bull slaughtering with the daily rural life of the animals. So, for them, the feelings and emotions contained in this shot are absent.

This example shows that the revolutionary filmmakers encountered the following difficulties in the new Soviet Union: moviegoers changed socioeconomically; but in Eisenstein's view, this class difference determined their spiritual and Differences in emotional life. That is, for different class members, the same perceptual stimuli lead to different associations and thus different emotional outcomes. But in the Soviet Union in 1925, the social need of filmmakers was to mobilize all audiences to participate in the construction of a socialist society, so that the film industry and art could be an important vehicle for conveying new perceptions and purposes, which were essential for building society It is necessary for the task of ideology. To overcome the social differences of the audience, wouldn't it be ideologically beneficial if aesthetically generated emotion could generate a commonality of bystander emotion and thus a common ideology? Although the emphasis on montage in Eisenstein's early works was all on arranging conflicts and contradictions, this emphasis led to problems of emotional consistency in the viewer. This is the real essence of the failure of the film Strike. The question of how the audience can be emotionally unified became central to later Eisenstein's theory of film form, the film-viewer relationship, and his most fundamental theory of aesthetics in general. For example, a few years later, until 1929, Eisenstein was still using the discourse of conditioning, describing the target as "a single stage of collective enthusiasm" in which abstract concepts or ideas become "a collective experience perception". Eisenstein here describes a successful lecture as a pattern, but he then makes it a matter of form, and argues that cinema is the only one of its time capable of eradicating the conflict between the language of logic and the language of images (obraz) art form, thereby restoring enthusiasm for ideas (ideologies).

So far, my discourse has framed the problem on several key oppositions between an immediately emotionally divided audience versus an emotionally unified audience, and a socially differentiated audience versus a collective audience. But the fundamental problem of Marxism in "The Making of Workers' Films" might also be recognized as a modification of these oppositions as: The opposition between a socially stratified audience and a classless audience, or at least with a classless audience Opposition between divided audiences. Audience not divided by class? Or better to say, the audience is class-differentiated at the beginning of the film, but becomes class-free during the viewing of the film? This responded to the official Soviet goal of creating a classless society. (In fact, by the mid-1930s, Stalin himself had publicly declared that because the Soviet Union had succeeded in eliminating class exploitation, the class contradictions among the few remaining classes, workers, peasants, and intellectuals, had been eliminated. In Stalin's view, although this was not a completely classless society, it was the result of a "lower" phase of communism, and the Soviet Union was on the way to a "higher" communism that fully realized a classless society. But it is certain Yes, films or works of art cannot by themselves create a classless society. One reading suggests that this may mean that the emotional unity of society envisioned by Eisenstein would be a utopian experience. Because while it assumes society is moving towards a classless future Marching, but classless spiritual experience is temporary and actually exists at the level of reception. Historically, the act of watching is predictable. Letting aside the empirical reality of the Soviet Union, we may recall that the Soviet Union formally rejected utopianism, Following Marx and Engels about their time, Eisenstein clearly did not espouse explicit utopianism. But we can explore whether the question posed in The Method of Making a Worker's Film implies that utopia can help to define problems, These questions lead Eisenstein into his extensive later studies and work on aesthetics. If so, what are its conditions?

In this article I have only tried to illustrate a few general directions about Eisenstein's 1935 speech at the Innovation Conference of the Union of Soviet Filmmakers; this speech was incorporated into his later film theory and film aesthetics. Eisenstein publicly announced in his speech that important new developments in his concepts of form and montage were related to the act of viewing. This is an essential version of Eisenstein's speech, and it should be read in contrast to the first version, "Speech to the All Union Creative Conference of Soviet Filmworkers". It should be noted that this speech was only slightly earlier than Stalin's statement that class contradictions in the Soviet Union had been eliminated. Especially in his later works, he incorporated knowledge from fields including aesthetics, anthropology, history, philosophy, rhetoric, as well as art history and film art. He began by only lip service to the emerging term socialist realist aesthetics, and went on to insist that form was central to film theory and aesthetics, as well as to the social function of film. He rather boldly retains the questionable formalist term "montage", but he introduces the new concept of spectatorship into his theory for reflection. Two new concepts will be pointed out below—mainly inner speech and prelogical thought or sensuous thought; and then to the act of seeing, which is seen as a kind of emotional unification and innocence. class.

Internal language was an important concept widely spread among Soviet intellectuals at that time. In addition to Eisenstein, internal language was very important to Bakhtinian linguistic and literary studies, and played an important role in leading Soviet developmental psychologists, especially Levi Vygotsky, whose Colleague Alexander Luria was young and promising and had a close relationship with Eisenstein. Psychologists' research focuses on how children link thought and language as they develop language learning. Their research shows that young children's mental life goes through an internal language use stage, in which they use language to mean themselves rather than others. Such internal dialogues or internal language may absorb elements of external language. But young children use language differently than adult external language, which often has social functions, needs to be made clear to others and is therefore subject to certain logical constraints. The reason is that the operation of language is different when the internal language is directed to oneself and not to others, especially in terms of the operation of syntactic principles and semantic processes. On the other hand, the reason is that there are still some internal languages left in the adult thinking process, and it still plays a role in the adult thinking process. Writing as Marxists, Vygotsky and his colleagues inferred many things, including the social and historical nature of individual subjectivity, and the social and historical nature of thinking. For some advocates of internal language, especially for members of Bakhtin's school, internal language means that in all language use, any discourse presupposes internal dialogue, or as Bakhtin calls it based on the theory of dialogue. For Bakhtin, the idea of the inner life of these dialogues proves that mentality and individuality are social, and that these multitudes of inner voices are related to being multiple social voices. voices) are part of the literary works. This is not to judge the discussions and influences of this period about internal language, which are more nuanced, nuanced, and different than I have shown in this article. There is a discourse that carefully screens out the subtle differences between Vygotsky, Bakhtin, and some members of the Bakhtin faction, but the book treats Bakhtin as anti-Marxist, which is not what I think in this paper. to be discussed. I have said elsewhere: Vygotsky and his comrades, the Bakhtinists, and Eisenstein should all be regarded as innovators of Marxism, who actually engaged in theoretical discussions in Stalinist culture and tried to to intervene in it. They invoked internal language in the late 1920s to mid 1930s, each with different results.

When he talked about the "audience" of film in his 1935 lecture, he stopped talking about the concept of stimulus and response, however, if it is claimed that Eisenstein's later writings no longer have any reference to physical structure or physiological structure, or mental The shadow of neural activity and reflexes in the world is wrong. After all, this approach does call itself a materialistic psychology, a term occasionally found in Eisenstein's later writings. But Vygotsky and the Bakhtinists did use the concept of internal language to counter Pavlovian psychology, and there seems to be some sort of shift in emphasis in Eisenstein's work as well. It is worth pointing out that Eisenstein was also aware of certain psychoanalytic theories, however it is politically impossible to explicitly mention psychoanalytic theory positively in his writings of this period. Rather, it uses internal language as a core element of its thinking about audience and form. Like Vygotsky, his distinction between internal and external languages emphasizes syntactic principles and semantic processing. From a semantic point of view, he was convinced that the words of the internal language designate the specificity of objects and the concrete forms of objects, rather than aggregating things into abstract concepts. Therefore, these special properties become the basis for the concept of associative thinking. In addition, the dominant trend of external languages is to make words into abstract categories or abstract concepts that aggregate the properties of things, and these concepts have logical consistency. However, the syntax of the inner language depends on the figurative connection between the specific nature of things and the signs that designate them. Eisenstein emphasized that the two classical metaphors, metaphor and synonymy, established the syntactic principles of internal language. If we see internal language as a continuous flow of thought that connects the object to which the object's own properties refer, then one might think that their connection is imagery or even poetic. This allowed Eisenstein to compare internal language to montage as well as poetry.

Eisenstein also believed that these connections are perceptual. This is important for the current discourse. This makes the inner language the language of emotion, and the flow of thought of inner language also becomes the activity of emotion. He often refers to internal language as emotional thinking and sensuous thinking. Like Vygotsky, Eisenstein also firmly believed that the external language did not ban the internal language, and that the two levels of language coexisted peacefully and interdependently in spirit. For Eisenstein, this meant that emotions were always present at the level of thought and under the logical construction of external language.

But what does all this mean for form and spectatorship and for unity in relation to classlessness? Perhaps we should start with an assumption that Eisenstein held to throughout his life: he believed that the special emotions that film and art evoke must be traced back to their form. If internal language is the activity of emotion, it must have an active form; this is analogous to the fact that concrete qualities and the particular signs that refer to it are linked according to principles such as metaphor and synonymy. And the link between this and what he says is the main finding is clear. He believes that the activity of perceptual thinking is not only the basis for the perceptual appeal of a film or a work of art to the audience, but further that this is because the aesthetic form functions in a way that is actually similar to the way the syntax of perceptual internal language functions. : The laws that construct the inner language are the foundation of the whole multitude of laws upon which the composition and form of the work of art are based. In film or any art form, all normative mechanisms are constructed to mimic the laws of internal language (as opposed to the logic of external language). While it was previously thought that the intellectual work of film must be read theoretically in terms of the history of the art form and the continuity of film with earlier art forms, Eisenstein's view actually offers a new way of reading: in art there is a There is a gradual upward trend of ideas at the top of consciousness, and at the same time there is a tendency to penetrate into the deepest part of perceptual thinking through the structure of form. The binary opposition between these two trends creates a magical tension for discerning the unity of form and content in serious works of art. This lecture in 1935 publicly laid the foundation for the development of an extremely complex aesthetic theory to which Eisenstein devoted the rest of his life. But this foundational view is relatively simple, but it provides a new justification for Eisenstein's later focus on aesthetic form: the "content" of a work is the idea that the work inspires. The generation of this view is social and historical. This might be understood as something like "ideological production" in historical materialism produced), and its emergence led to the practice of cinema. But the aesthetic form imbues the concept with emotion, and this engages the viewer in the dynamic construction of the work, and thus engages the ideology in this way. Forms are thus made dependent on imagery figurative forms or syntaxes which, as previous studies of internal language have revealed, form affective activities. The correspondence between the form of art and the form of the internal language constitutes the reason for the special emotion of a successful film or work of art, and this correspondence makes it ideologically influential.

It can be said that this new vision provides a solution to the problems raised in the above-mentioned article "The Making of Workers' Films". Although everyone has different emotions and thoughts, all emotions are organized in a similar syntax or form. If the flow of emotions is controlled by the same syntax in all people, then this means that emotional forms are superclass; in the same way aesthetic forms follow emotional forms. If we go back to the previous search for classlessness, that search will probably be dispelled by the universal inevitability of irrelevant history. In 1925, he had said that the failure of the film "The Strike" to not unite the audience was a formal failure. In the ideological framework of the 1935 lecture, it was still a failure, but the meaning of the word "failure" was different. When audiences are perceptually divided by different class groups, it means that filmmakers fail to find a solution in their creation, and that solution is to use characteristics similar to the general forms of human psychological processes, so that the Audiences break away from their long-established class positions.

But in this case the solution is actually a form of universal necessity. And, in this case, the important part seems to be irrelevant to history. For in this case the form itself is not historical, although it is fundamentally social and historical. In order to think fully about this issue, we must further discuss another major point of the 1935 lecture. It's about culture and pre-logic. In a crucial step, Eisenstein extended, by analogy to individual-phylogeny, the sphere of what he saw as the peculiar nature of affective or perceptual thinking about the cultural whole. As individuals, children go through their early language stages in which their inner world is dominated by a perceptual, figurative idea. This is called inner language or perceptual thinking, which he also called pre-logical thinking. Besides, it will not disappear completely, it is the basis of later external language and logical thinking.

In his 1935 lecture, he went on to envisage the existence of parallel stages in the historical process of human culture that parallel individual psychological stages, discovering the same structures that underpin cultural practices that transcend the individual. For this he draws on anthropology and related linguistics, especially Lucien Lévibriel's concept of "primitive mind". Eisenstein was strongly attracted to the idea that the origins of culture are presented through contemporaneous primitive cultures and languages, as well as the forms of pre-logical thinking that govern cultural practices and rituals and the egocentric internal language of children. Likewise, this idea also attracted Eisenstein. He argues that the principles of pre-logical thinking that govern internal language also govern customs, rituals, and the everyday cognitive structures of non-modern forms of society, and that what we moderns think of as fantastical thinking actually ignores logical distinctions. For Eisenstein, these were social formations at the "dawn" and "threshold" of social and cultural development, and they showed a "pre-logical" "early form of thinking." They may have been surpassed by modern society, but like the internal language of individuals, they have never disappeared. This means that the minds of primitive cultures operate in a more concrete and perceptual way than contemporary industrial cultures. Now, there is every reason to focus on the concept of "primitive" thinking of original cultures. First made by a French thinker during the colonial period, these distinctions were considered equivalent to racism, as did Eisenstein himself; but today anthropology does not recognize them. In terms of the evolution of Eisenstein's view discussed here, on the one hand this can be seen as an endorsement of the Marxist idea that social formation determines mental state. On the other hand, it also means that the mature art of modern society exists in the interaction of whole and part, inner and outer, pre-logic and logic, sensibility and reason.

This also leads to another concept that is very important in Eisenstein's search for unifying audience emotions: regression. That is, regression is one of the properties and benefits of a work of art. Because the individual she or he will fall into emotional thinking or be deeply moved by movies or works of art, there is a spiritual regression, but this regression is not only spiritual, but also historical and cultural, coexisting with modern people and survive in modern times. The paradox of regression lies in the fact that the appeal of the art form is related to the remnants of childhood and pre-modern cultural practices; and the appeal of regression makes art ideologically beneficial to modernization and even the construction of a communist society. In post-Eisenstein theory, regression is the condition of emotionally uniting the audience. Thus, it is the regressive appeal that makes Eisenstein's later theory a possible utopia in which audiences are free of social and class differences.

Within the confines of orthodox Marxism, you might think of Engels' account of an almost prehistoric primitive communism. On the other hand, you might also rethink the utopian idea of Western Marxism, which is not about the imagining of an ordered space in a perfect society (a utopian social improvement program), but rather, as Ernst Bloch and Jan As revealed in some of Merson's works, it is an implicit desire or wish. In any case, Eisenstein spent the rest of his life thinking about the idea of regression and its human contagion, and though he was cautious at first, he became engrossed in it. He always associates it with an emotion that tends towards indifference. His fascination with establishing the link between regression and indifference led him to a concept of the plasmatic. This means that not only new forms but also new objects are continuously generated and presupposes a primordial fluidity of things that is not present in everyday logic. He sometimes sees it as the equivalent of amoeba, womb, maternal love, gender differentiation, the basic malleability of things, etc., because its contagiousness goes back to the source of things, when things are in the womb, in the mother, or in their physical nature. Formless, undifferentiated state. Eisenstein's paper and treatise on Disney contains a definition and discussion of Plasmatic. Eisenstein may have referenced Engels' thinking on these issues, and in fact he did so often, as in Dialectics of Nature, first published in 1925 and officially endorsed. This was fortunate for Eisenstein, for he was able to quote from it in his claim that life is an endless movement, becoming, and evolving.

What about classlessness? At this point we may be tempted to ask whether the inner logic of utopian thought always expresses wishes that can only be realized through regression? In Western Marxism, utopia does not emerge as an utopian spatial structure and a perfect society, but as a hope and desire, often unconscious, that contributes to a social drive and also inspires aesthetic and cultural practice. Bloch and Jameson are, in fact, the benchmarks for this view. But what if someone believed that utopia could be realized? As early as 1936, Stalin claimed that the Soviet Union had established a society close to utopia. See Stalin's treatise. In this article I have tried to show that Eisenstein's act of viewing can be read as a utopian urge stemming from a desire for classlessness that arises at a precise historical moment and ends with ahistorical universalism . But does this make this audience theory a manifestation of the utopian hopes, visions, and dreams of Western Marxism? And could it serve as a thread linking Eisenstein's later theory to Western Marxism rather than seeing it as a compromise to Stalin's aesthetics? If so, perhaps Eisenstein could lead us to consider whether the appeal of such a utopian vision is in part attributable to regression, imagination, or something like that, as psychoanalysts say when they interpret dreams . These questions require more extensive exploration, and for this article, we must end here.

View more about Stachka reviews