They crawled in the direction of the bushes, Rybakov in front of Sotnikov behind. It's been a long, grueling journey. Sotnikov was often unable to keep up, sometimes completely stuck in a ditch, unable to move, when Rybakov reached out and grabbed the collar of his coat and dragged him to his side. Rybakov, too, was exhausted, and from time to time he had to take not only one Rasotnikov, but two guns, which always slipped off his back and dragged in the snow.

In the midst of all the anxious expectations, Rybakov was distraught, listening to Sotnikov's feverish breathing, and felt disgusted in his heart. Rybakov was not bad-hearted, but he was born with strong muscles and bones, so he was not very considerate to patients.

This is the winter of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union, and the battlefield situation is stalemate. Sotnikov was an artillery company commander and a math teacher who had graduated from a normal school; Rybakov was a division chief, an ordinary farmer who knew only a few baskets of big characters. They are now exhausted stragglers. On a mission to find food for partisans stranded in the swamp, they encountered a small group of German troops. Sotnikov was shot in the leg, and Rybakov never gave up on him. Unfortunately, the two were captured by false police. The owners of the two families who had taken them in were also taken to the torture room of the false police.

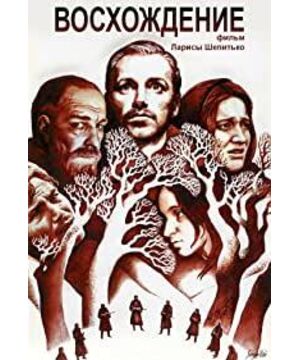

This is where the story unfolds. The film "Rise" based on the original book "Sotnikov" by the trench-realist author Bekov has an uncomplicated plot. In front of the murderous German army and the despicable fake police, Sotnikov withstood the torture, righteousness, denounced the shamelessness of the fake police, and unfortunately was hanged by the fascists. And Rybakov was greedy for life and fear of death, betrayed and surrendered to the enemy, and finally became a lost lackey.

The text already provides two typical images for comparison, and the plain picture respectfully unfolds the narrative.

Rybakov, who first appeared in our sight, was a powerful man who would rather perform a hundred raids than boring tasks, such as finding food for his team members. The high fever made Sotnikov want nothing, he was a big burden to Rybakov's slander.

In a scene at the village chief's house, Rybakov was still eating a hot meal a second ago, and the barrel of an uninvited guest was on the back of the host the next second, and Sotnikov also complied with such a thing" atrocity". In the end, Rybakov's goal was the only fat sheep in the village chief's family. At this time, the director seems to have deliberately confused the motives of the two people. Disapprove of Rybakov's rudeness, and you can also question Sotnikov's inhumanity.

With the slightest foreshadowing of the details, the reason why Sotnikov has become a hero living in the hearts of people, while Rybakov has degenerated into a traitor who is despised by others is because of their family upbringing, social environment, life experience, and even fighting The encounters are inseparable. In different occasions and tests, such as his encounter with the pseudo-police patrol, his attitude toward the interrogation of the enemy, Sotnikov's belief is to sacrifice himself to save others, to never surrender, even at the last moment of life and death, He also thought of taking everything on himself, in order to cover innocent people from escaping the clutches; and Rybakov was extremely annoyed by Sotnikov's "stubbornness".

The theme is the main theme of revolution and sacrifice, and the method is the stereotyped duality, but director Shepitiko successfully made the sublimation of the soul within reach and the casting of heroes down to earth.

In essence, Sotnikov sacrificed himself for others. In fact, this kind of sacrifice is not all for others, but also what he needs. If he thinks that Sotnikov's death was just a meaningless accident at the hands of those villainous lackeys, he himself would never agree. Sotnikov's death, like every sacrifice in a struggle, must affirm something and deny something. He could not sympathize with those who were willing to work under the German army and work for the invaders in various ways. Even if such a person will find various reasons to defend, it is difficult to move Sotnikov's heart. He knows that gullibility of such reasons will come at a price. During the brutal struggle against fascism, no reason, not even the most plausible reason, can be taken seriously. Only by ignoring those kinds of falsehoods can you be invincible.

Rybakov once said, "My good brother, I will come back to you", while blowing hot air into Sotnikov's neck to prevent the sick seedlings from freezing. Rybakov's cunning is that although he has been unwilling to wait to die, he feels that he can smash the entire pseudo-police headquarters to smash and strangle the intimidating pseudo-cops to death, and he eventually falls but begs for his own life. on the ego. The most terrifying thing is that we, the audience, often empathize with Rybakov. In the fierce confrontation, the fighting spirit is high, but the spiritual dam collapsed in the long torture.

Before the hanging, Sotnikov suddenly smiled as he approached the end of his life. His eyes searched for the thin boy in the Buddyoni cap standing blankly in the crowd. "Braveheart" once worked on this bridge, and it doesn't matter if Wallace beheaded, there will be his own descendants, and the spirit of freedom will be passed down from generation to generation. But it is also a charming smile in desperation, but we can only capture the sorrow in Sotnikov's heart - what is life to those who dare to trample on it?

The female director points the camera at Sotnikov's face ready to suffer. Although, in the film, Sotnikov has a faint disgust for the old village head appointed by the puppet army, who is rubbing the black-skinned Bible, and "not a good comrade of the Bolsheviks", and the camera stares at his clear separation for a long time. With a materialistic face, even if he is a staunch atheist, it is still reminiscent of Christ's redemption, or, the Russian-style Holy Fool. A typical example is Duke Myshkin in "The Idiot". Holy Fools make it their priority to fight their sin and pride, and for this they are either angry or insane. For some, they are ridiculed for losing their minds, but the Holy Fools use metaphors or symbolic words and deeds to expose the evils of the world.

When Jesus Christ suffered, how many people have sacrificed their lives for mankind, but how much have their actions taught mankind? Just like thousands of years ago, people think about themselves first, so that kind of high-spiritedness that resolutely sacrifices one's life for righteousness, sometimes in the eyes of others such as Rybakov, is either stupid or absurd. Is it worth Sotnikov to lay down his life for someone who wants to live at any cost?

The saint and the mediocre, in just one thought, have heaven and hell. Describe the immortality in man, revealing its qualities rather than insulting him, so that the soul can be illuminated.

Instead of the thick oil painting style used by Sholokhov or Bondarchuk, there are light watercolor smears and even Coleridge's prints. The female director did not hesitate to abandon the complicated colors, and concentrated on rendering the revolutionary theme with black and white and long shots. For example, in the opening scene, which is prone to snow blindness, Rybakov and Sotnikov walked in and out of the bushes, and the sad eyes of innocent girls in the cell. Action scenes, the picture is shaking, the camera is not fixed, but the tracking of a strange third party is presented by carrying a hand on the shoulder. A shot is so long that it is daunting, but you have to sigh the texture of the scene. The objective narrative and the subjective lyric are blended together. The lens is not biased, it is not whitewashed, it is not beautified or even elevated, Sotnikov's sublimated image radiates extraordinarily heat. All the incantations in the complex form weave a series of preludes to the ascension of humanity.

At present, we are trying to make the main theme into a commercial film, attracting the audience to pay a lot of money. As for whether it is educated or shocked, we have no way of knowing. The Soviet film tradition is to poetize the main melody. Even if those elements of the era are eliminated, it can still be among the classic halls and a poetic dwelling.

"Watching the Movie"

View more about The Ascent reviews