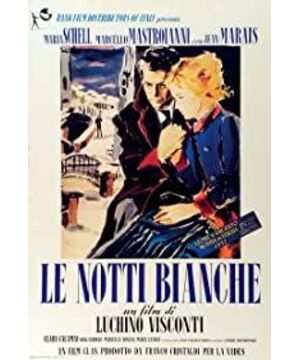

"White Night": Visconti's Realistic Narrative

2009-12-04 10:08:21 Source: Editor: Hao Yanwen

/ Drifting Everywhere

"White Night" has always occupied a central position in Visconti's career. On the surface, at least, it was the perfect end to the neorealism of the 1940s and early 1950s, looking towards Leopard (1963) in the subjective representation of visual style, and Approaching The Big Dipper (1965) in its structural setting of increasing reliance on metaphors. But appearances cannot be trusted, and in 1969 Visconti returned to realism with Rocco and His Brothers. By its very nature, White Night is basically a realist film, despite its shift to fantasy.

Visconti has always preferred to start with the original literature to accommodate the varying degrees of freedom that accompanies his adaptations. White Night is an especially successful blend of autonomy and reverence—he and his writers achieved their mission. The story takes the title and basic framework of Dostoevsky's 1848 short story. In stories and movies, it's about a lonely young man meeting a lonely young woman. Mario's loneliness comes from socializing: he is new to the town and is a stranger; Natalia's loneliness comes from living in isolation despite being in the center of the city, and this loneliness is caused by falling in love with another man Intensified. This man may come back, or he may never come back, but he occupies her life to the point of cutting off any possibility of her developing other relationships. During this four-night period (late spring in the story, winter in the movie), Mario gets the chance to get to know her, fall in love with her, and finally lose a year of news about her long-awaited love. Lose her by returning from the promise.

In transforming Dostoevsky's original book into a film, Visconti dropped the first-person perspective and made the young woman a little less innocent, in fact, more or less Hysteria and love and teasing. In the midst of these changes, he also made the ending more sad. The narrator in the novel has the opportunity to conclude, thanking the girl for a moment of joy. In the movie, however, the hero is set aside, teasing the same stray dog he met at the beginning of the story, and returns to the square, not seeing any impact from that brief love affair.

Visconti was determined not to make "White Nights" a costume drama, but to set the story in 1957 and bring Dostoevsky's plot from St. Petersburg to Italy. He gave up his habit of shooting on location, and instead shot all the scenes in one workshop. In order to achieve a tight geographic focus, the director and crew built a large set, and many smaller ones, roughly in Livorno, in the Tuscany region. The big set is a typical 1950s Italian city street with gas stations, shops, eateries and neon lights. Compared to the real but accidental artificial atmosphere of the setting in "The Enchantress of the Warring States" (1954) (note, Senso), the setting here is chiseled and deliberately made to feel this effect. This is partly due to photography and lighting, both of which create an unexpectedly dreamy visual effect, with unusually progressive contrasts that remind the viewer of the poetic realism of Marcel Carné's films. But on the other hand, it is also attributable to the respective presentations of the characters under the influence of their own environment.

At the end of the street is a bridge that spans the waterway, where Mario meets Natalia sobbing and overlooking the river for the first time. The main spatial metaphor in the film comes from the waterway that divides the set into two distinct worlds, and from the bridge that connects the two worlds. This division is more suggestive than declarative; more metaphorical than allegory. On one side of the bridge is the world where Natalia lives with her blind grandmother, and on the other is the earthly world of the city, where Mario lives. This spatial division doesn't just isolate Natalia geographically. It is a symbol of this series of contrasts - memory and status quo, public and private, fantasy and fact. Natalia's world is nothing but herself, her grandmother, her aging girlfriend, and the mysterious lodger she falls in love with—a world that is part status quo, part memory, part imagined world full of secret relationships. Drawn across the bridge and approaching Natalia, Mario is forced to partake of this private world full of fairy tales, to share its visions, and to merge them with his own. But he never really stepped into the world, and for him it kept its daydream color. He knew it through her—through her imagination; his picture of the world was compounded with imaginary elements, partly her whimsy and partly his own.

After the visions of these two wishes - Natalia wishing her lover back, Mario wishing he could bring her out of this isolation - the changing, subjective contrast, there is the static, objective contrast. Much of it echoes the contradictory foundations of Visconti's other films: especially noteworthy are those between sinful passion and easy love, eternal and fleeting, past and present, tradition The contradiction between culture and popular culture. These contradictions are most vividly expressed in the contrast between Natalia visiting her old grandmother, the lodger going to listen to Rossini's "The Barber of Seville", and rock music in the diner across the bridge. The world, flashy modern on one side of the bridge, and infinitely ancient on the other side where Natalia lives with her grandmother. So Mario's task is to lead her across the bridge into a world full of life, expressiveness and modernity. This happened on the third night. He first tried to take her to the cinema, but since the movie was already on, they moved to the diner where a group of young people happened to be dancing to Thirteen Women (And Only One Man in Town). Mario persuaded Natalia to dance with him, and at first the two were unbelievably clumsy. Then Mario joined the dance floor with some of the best rock rhythms ever seen in a movie theater. Despite the tediousness of his movements that signal aging, Mario is relaxed and happy, and even manages to dominate the dance floor, leading in the style of Jerry Lewis. Visconti is far from a pop fan, so pop here (and later in The Big Dipper) symbolizes the negativity of modern society. But when faced with such an opportunity, he threw himself into it. The song was stretched to twice the size of the original, which helped Visconti expand his characters and personalities and tear them apart with music and dance. Natalia's clumsy attempt to keep up, her hilarious embarrassment, and Mario's unexpected self-presentation all reveal their characters as much as the dialogue. In this inhuman environment, they are separated by other dancers, and they try to break through the barrier to establish some kind of physical intimacy. Again, as crazy as this scene is, it seems oddly unreal. By contrasting this scene with that of the Opera House, Visconti does not merely express his taste in music. On the one hand he explains the two protagonists and on the other provides a framework for understanding. This opera-rock contrast is neither isolated nor obtrusive: it is a necessary part of the film's symbolic architecture.

If we pay attention to the plot design of this film, its structural framework will be clearer. The two were sitting on the bank of the waterway, and she told him about her life, and the sideline merged with the scene she was describing. Mario doesn't approve of the whole story, he finds it unbelievable. From beginning to end, she was trying to keep her eyes on him. She gushed about herself, moving between expectations and disappointments, and between rejecting and encouraging the unfortunate Mario. He resisted in vain. He thought he could remove her from the world of self-imagination. Already a dreamer himself, he obeyed the visions and allowed himself to be drawn to her and her world. At the same time, however, he was always on that side. To her, he was insignificant. Her disregard for the real world is as he disregards her whimsical power. Throughout the film, we face a conflict between two levels of reality, the real and the ideal. The real reality is portrayed as ephemeral, modern, socially alienated, pop music, young people on motorcycles, prostitutes with her customers, and strangers. And that ideal reality, by its very nature, pays less attention to certain specific scenarios - it is the product of the alternation of the forces of fantasy. The same spatial contrast exists in the characters themselves. In her imagination, she was loved with all her heart, and because she believed in love, her lover would come back eventually. The extraordinary thing about this film is that her triumphs, ideals come true. At the same time, White Night is not a sentimental film, it is clear, and always bears the stamp of realism. Thus, although Visconti has been criticized since "White Nights" as abandoned from the 1940s to the early 1950s, to be precise, from the time he first met Jean Renoir in the 1930s, the new Realistic style, this comment is not infallible. In 1957, there was nothing left of neorealism to throw away, and Visconti's approach to neorealism was always selective. Realism for him is not so much a destination as it is a means. Compared with "The Sinking" (1942) or "The Earth is Fluctuating" (1948), "White Night" is indeed not a work of realism, and this work does have an obvious style of fantasy. However, his "White Nights" is also not really different from his other works, either earlier or later.

He chooses stories—realistic, as in "The Earth is Fluctuating," or whimsical, as in "White Nights"—and gives them a strong sense of reality behind the truth of human nature. This process is full of realism, both stronger and weaker. Unlike Rossellini or Antonioni, he has no room for hesitation. Everything Visconti shows shows his belief in the real, strong performance as much as possible. When he tried to adapt Camus' "The Stranger" more than a decade later, it turned out to be a disaster. The same can be said about Thomas Mann's "Death in Venice." All the subtleties and intentional ambiguities of the original are wrapped up in large, flat statements.

But in "White Night", this balance is perfectly maintained. The well-placed narration and progressively erected characters lend substance and coherence to the otherwise thin story, without sacrificing the dreamlike atmosphere of the original. Yet the charm of Dostoevsky's story comes from the fact that one can never rationally believe it, and in the film, trust is possible and necessary. When the tenant shows up at the end of the story and takes Natalia away, the doubts stop for a while. But full of disappointment, Mario, who was left alone with a stray dog, continued his ruthless real life.

View more about Le Notti Bianche reviews