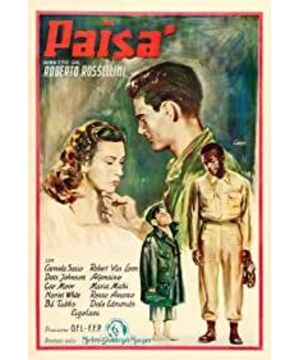

Roberto Rossellini's second postwar film was released in the United States under the title Paisan, which means "friend" or "compatriot" to Americans, and is used in this film reflecting the virtues of fraternity. It is also suitable for the movie. Its Italian title is Paisà, which in the Neapolitan dialect is a friendly name for the villagers. The film outlines the country during the liberation of Italy with 6 stories that took place in real locations in Italy. 6 separate fictional chapters, from south to north, follow the journey of Italian liberation. There is no close connection between chapters in terms of theme and atmosphere. Some are horrific tragedies, such as the first stanza, the death of a young Sicilian girl named Carmela; or the last stanza, the massacre of partisans by the Germans on the Po River. Others are disturbing comedies, as in the second stanza, where a Naples street boy steals the shoes of a drunk military policeman; or the fifth stanza, where a Protestant and a Jew (the U.S. military) enter a Franciscan monastery in northern Italy. , which caused some shocks. But the film's theme remains the same: the linguistic and cultural clashes that followed the Allied invasion of the Apennine during the miserable years of 1943-44.

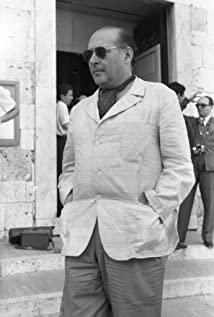

Compared to Rossellini's first postwar film, "Rome Undefended," "War" is a huge improvement in terms of funding. The former was made with sporadic funding and scrap film, but its success gave Rossellini the ability to carry out a shooting program with ten times the budget and US funding. The "Fire of War" filmed is an extraordinary achievement. French film critic Bazin believes that "War" is to European films what "Citizen Kane" is to Hollywood. It greatly enhances the ability of films to capture reality. Bazin believes that Orson Welles' innovation is at the level of form and technique. Using new lenses from the 1930s, he creates depth of field that allows viewers to freely extract meaning from complex images. Rossellini's photographic sophistication and powerful capture of reality are achieved through a miraculous blend of documentary and drama techniques. The most obvious is the use of non-professional actors; the reason why the streets of towns appear so vivid in "War" is that they live in them, not actors, but men and women suffering in the horrific reality of postwar Italy. , the children, and the American GIs in the mix. The most moving scene of this performance takes place in the opening story. Carmela, who leads the way for the US military in order to find her father and brother, is played by an untrained 15-year-old girl, and the sympathetic atmosphere of the entire opening story But mainly from her excellent performance.

It would be a big mistake to think that Bazin's alleged blending is the result of simply superimposing reality on fiction. Analyzing the case of Carmela, we will see how complex Rossellini's process of creating reality in front of the camera is. Carmela is not actually a Sicilian, but Rossellini found in a village in Naples. The "truth" that can be found in her is not some simple certainty, but her spiritual independence and her tangible distance from the surrounding Sicilian villagers. This gave her the strength to set out with the American soldiers regardless of the other villagers. But if the interaction between villagers and outsiders is the real side of the film that the film is meant to capture, a part of the life that it wants to enter, it gives another more realistic element to the film—the various dialects spoken by Italians— - caused a problem. Italy is not one country, but a collection of many small countries, each with its own official language. Carmela's Neapolitan dialect is incomprehensible to Sicilian, so she was dubbed. In the monastery section, dubbing is used again, because the monastery in the story is located inland in Rimini in northern Italy, while the monastery filmed in the film is in Salerno in the south. The dialogues of the monks who spoke the Neapolitan dialect were dubbed in the Roman dialect.

Rossellini's realism, therefore, cannot be understood simply as a representation of reality, but as juxtaposed elements that only become real when they are captured by the camera. This is very evident in the way he places fictional elements in real locations. Much of the power of the final shot of the third quarter (American soldier Fred leaves Rome without finding the girl he fell in love with six months ago) comes from the fact that he's waiting outside the gym for a truck to pick him up. The shocking force of the second part of the Naples story comes from the slums of Mergellina, where street children live. When Rossellini discovered the ghetto, he dropped the original story idea in favor of the one we see in the movie. The most striking use of location comes in the fourth quarter, where an English nurse and an Italian man travel through the famous streets of downtown Florence in search of lovers and children. These famous streets are turned into battle fronts between Germans and Italian partisans in the film, while the Uffizi Gallery becomes the usual shelter. The transformation of a historic city into a battlefield is most vividly shown in the following scene: a British officer is looking at the guide map, wondering which famous clock tower he is looking at, and the Florence native beside him is his wife Worried about his safety, he simply replied that I don't know.

Such misunderstood conversations are typical in movies, where language does not reveal the truth, but obscures it. In the opening dialogue between Joe and Carmela, neither side speaks the other's language. The film highlights the distance between intent and acceptance in conversation. Even when the two sides of the conversation understand each other, this distance often arises by accident. The end of the fourth quarter is a perfect example: the dying guerrilla tells the British nurse that Lupo is dead, completely unaware that the nurse is Lupo's lover. The emphasis on the misrepresentation of language seems to contradict the human fraternity that the film is meant to convey, and Rossellini does not resolve this contradiction, but keeps it at the heart of the film.

The original promotional material described Fire of War as a film celebrating the liberation of Italy by the US military, but Rossellini ditched the earlier film when he found a real theme in the filming (the real life of Italians in 1943-44). script. But the film does end with a sincere portrayal of the partisans fighting side by side with the U.S. Army on the Po River. This last section is widely regarded as the most realistic of the chapters, and is a grand summary of the entire film: the drab view of the Po wetlands, the boundless horizon, the harsh conflict, and the unpretentious presentation of peasant life, all in The audience lingered in the memory. Instead of focusing on the American victory in Italy, as initially envisaged, it focused on the brutal German slaughter. Compared with military victories, there is something more touching and more real in the shared responsibility for difficulties and failures.

Any simplistic description of "War" would make the film seem painful and hopeless, but the dynamism of the story, the camera's ability to perceive reality as if it were facing a new world, makes it one of the most exciting and dynamic films. The film won an award in Venice, but its reception in different political camps in Italy was mixed: for communists, it was too Christian; for Christians, it was too communist. But internationally it received unanimous acclaim from critics, especially in France, where Bazin used it as a pivotal film to illustrate the importance of Italian neorealism.

(by Colin MacCabe, author of "Portrait of the Artist at Seventy" by Godard)

View more about Paisan reviews