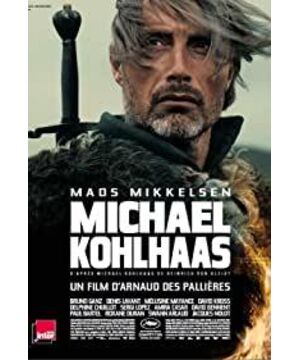

"Sing, Muses! Sing the wrath of Achilles, son of Peleus, whose wrath brought this terrible calamity, and brought untold suffering to the Achaeans." The source is an epic about "Rage," which Heinrich von Kleist's original is not. "Michael Kolhaas" is about the 16th century merchants who were unable to defend their rights in Germany, where the princes ruled. The story in the original book took place on the border of Saxony and Brandenburg, and used a lot of ink to describe the open and secret struggles of the aristocratic class. In the end, Colhas was able to obtain the so-called "justice", which was actually the joint result of the struggle between the princes of the two countries, rather than the ruler's conscience discovery or the "rule of law" at that time. Now the movie version has cut off a lot of these contents and simplified the plot to a higher theme, which is "Korhaas' Wrath".

Anger is the source of calamity and suffering, this has been true since the time of Homer. Alan Bloom's explanation for this is that anger is always associated with "defending one's own things". The case of Colhas illustrates this point: his anger, which began with the gratuitous abuse of his horses and servants, rose to a "desperate" rage over the loss of his wife - which, interestingly, was also "Achilles". "The Wrath of St. Paul's" went through the process: first, the anger caused by Agamemnon's unreasonable snatching of his female prisoner, and then the rage caused by the loss of his love friend Patroclus. And whether it is a demigod hero or an ordinary horse dealer, they will use their anger to start a "disaster and suffering", and they will inevitably lead to their own destruction.

For every sane "reasonable person", there is an inescapable ultimate question: Is it all worth it? The magistrate asked Colhas from the very beginning, "Can't you afford the loss of two horses?" would support this price/performance ratio. But in the eyes of the parties, this account is not calculated in this way. A person has his "deservings" to survive in the world. Whether these things come from the hard work of individuals, the inheritance and gifts of ancestors, or even for "professional warriors" such as Achilles, they are the spoils of war and plunder, in short, they are reasonable, legal, and should be respected and protected property. This is the foundation of all human ethics and values. Infringing other people's property without reason is not only a legal issue, but in an ethical sense, it implies a devaluation of the other party's personal dignity and status: only those who are not regarded as slaves or prisoners who violate the law are not allowed to own themselves property, or be forced to surrender property as punishment. Being able to own and defend one's own property is the defining characteristic of a free man.

In the era of Kolhaas, a feudal caste society was a reality, and the nobles were indeed higher than the commoners - although the merchants were free men rather than serfs of the nobles. In the original work, it was because the baron's relatives were the elector's favorites, which led to the judgment of bending the law for personal gain. The movie omits this plot, which makes it easy to misunderstand the social background at that time. In fact, Colhas not only owned farms and land, but also possessed weapons, indicating that he should belong to the squire class. Even the laws of that era had explicit protection of his property and rights, at least on a literal level with the nobles (so he was able to sue). It was the injustice that occurred in the specific operation that made him resentful, and finally reached the point of violent confrontation. In his eyes, without the justice of the law, one's property and rights cannot be expected to be protected by society, but can only resort to self-protection - relying on primitive personal strength to defend it.

That's the problem with "anger". In Plato's interpretation, "anger" is the antithesis of the city-state and the law. Unless this dangerous emotion can be eliminated from everyone, it is impossible to obtain an "ideal city-state" that is always stable and completely ordered. However, this "anger" is part of human nature, and protecting "one's own things" is a survival instinct that everyone must have. If a person can let others take or destroy their property, lose family members and not respond, then he is probably cerebral palsy. It is inferred from this that the so-called "ideal city-state" must be against human nature and cannot exist.

But that doesn't mean that "anger" is justified. Because "anger" is a paradox. Its purpose is to defend "its own", but it does not care about sacrificing one thing, and that is life itself. In Bloom's view, in order to justify the "anger"'s life-staking behavior, people will intentionally or unintentionally exaggerate the meaning of this sacrifice. "The tendency of anger is to give rationality and morality to selfishness." When the daughter asked Kerhas: Are you fighting for the horse? Is it for mom? The answer is "no". The bigger words are, of course, "dignity" and "rights." But no matter how much logic is constructed to support "righteous indignation," most acts of anger are still just "insanity." In the original book, Colhas's wife was beaten to death by guards when she was asking to see the elector. The movie version also deleted this detail, highlighting the ambiguity of the incident: her death should be attributed to the "stalking" of the horse dealer. Litigation", or the callousness of the powerful? Or just an accident? For the client, these details are no longer important, because "anger always puts the blame on the thing that caused the harm".

The priest played by Dennis Lawan who came to "call for peace" is in the original text Martin Luther himself (so the horse dealer would say "I read your Bible"). Luther was in the 16th century German peasant uprising He always stood on the side of the nobles, and said a lot of bad words. Apart from factors such as personal character, Luther's religious concept did not support "anger". He emphasized personal introspection and restraint on one's own soul. Although "anger" Defending rights has caused mental imbalance and confusion, and the killing and destruction in the process can dissolve the rationality created by "righteous indignation" for oneself in minutes. Therefore, "anger" can only be a kind of dangerous Sin, obedience and acceptance of fate are virtues. In those days, the value judgment of this religion had the most direct spiritual influence on Korhaas. It is not surprising that he therefore gave up resistance.

The end of anger is destruction. Social Order necessarily requires the tameness of these "angry people", and anger itself, as an emotion, will eventually have its time to subside. When it dissipates, what is left to the once passionate client is often confusion and greater entanglement. In this sense, death is not necessarily a relief. The minutes-long close-up at the end of the film has been focused on Korhaas's face, and those changing expressions are the masterpiece of this "anger".

View more about Age of Uprising: The Legend of Michael Kohlhaas reviews