Regarding the face of

others When he learned that there was a neurosurgery hospital that could make a fake face for him by covering his face, he decided to try to save his relationship with his wife, but after he put on a new face, he found that everything was not under the control of his personal will , He gradually got lost behind his fake face. In order to prove his outlook on life, he even wore a fake face to seduce his wife. After his success, he doubted the meaning of life, and he could never return to his own life. In the world, everything slipped in the opposite direction of the original goal, and the doctor who served him eventually became involved in an uncontrollable situation and became a victim of this medical experiment.

This film, which is also adapted from Abe Kobo's novel, is more like an image expression of Japanese existentialism theory. In the past 40 years, films with the same theme also discussed the ethics and self-identity after the masquerade. Therefore, this film exploring human cognition has great practical significance. The problem of face-changing in the film has been conquered by contemporary technology, but the problem of "who am I" is still a problem! The biggest problem of Yi Rong is whether the masked self will restrain itself with morality. This film is about the relationship between mask and self. This is the director's most existential-minded film. The self-identity he reveals is not only a concern of Okuyama after Yi Rong, but also an extended issue: people's perception of self in modern society role identification. How many people who live in the world of seeing people are what they really are, and all the things that are covered up called masks may be part of the multiplicity of people. There are many dialogues and self-talk in this movie about people's The problem of multiple personalities and masked life, the pan-philosophicalization of the film seems to be the experience of young directors, which makes the film less enjoyable. The surreal picture at the end of the film expresses the director's anxiety about contemporary interpersonal relationships. Everyone hides behind a mask, which makes Okuyama feel hopeless. In despair, he begins to move towards the opposite of society. The idea of this film is the basic argument of existentialism. "Others are hell", a person's physical damage can be healed by modern medicine, but the spiritual wound is difficult to heal.

What the director repeats over and over again is the importance of the face to the identity of the role of life. When the face is changed, the original value system is also changed, and human nature becomes unscrupulous behind the mask. The director designed a scene similar to Zhuang Zhou's wife test, wearing The masked Okuyama tried to seduce his wife, but he succeeded in one shot. The scene of exploring each other under the table was very tense so far. It marked emotional fragility, and desire rose in the hidden places of life!

What is interesting is that Jinger Henglu, well-known to the Chinese, plays a mental patient in the film. He is really good at this kind of role, but the setting of this mental hospital scene is related to the memory of the war that the Japanese cannot forget. From this point of view, we can see that the attitude of a really good director is always a bit of a face. This kind of thinking about the universality of human nature is inseparable from the modernist films of the 1960s. At the same time, the film is also prophetic about the present world, it makes us think about the real possibility of human nature! The music of this film was composed by Toru Takemitsu, full of sadness and ethereal spirit. This film was the fifth place in the top ten awards of "Movie Xunbao" in 1966. Further

reading:

An off-camera psychiatrist (Mikijiro Hira) overseeing a processed batch of prosthetic appendages describes his fragile role of diplomatically treating - not a patient's physical imperfection - but rather, the psychological insecurity that underlies his seemingly superficial malady. The curious, fragmented shot of randomly floating, artificial body parts is subsequently reflected in an X-ray profile of a smug and embittered burn victim named Okuyama (Tatsuya Nakadai) as he recounts to the quietly receptive psychiatrist his own culpability in the fateful industrial accident that had permanently disfigured him and now estranges him from his co-workers and family. The clinically disembodied images are then commuted into the equally cold and sterile Okuyama household through a dissociating,close-up shot of a human eye that zooms out to reveal his beautiful and mannered wife (Machiko Kyô) busily occupied in her hobby of polishing gemstones as the acerbic and insecure Okuyama attempts to test her affection and fidelity with vague and allusive casual remarks and open-ended questions. Spurned by his wife after a spontaneous and awkward attempt at intimacy, Okuyama returns to his psychiatrist and agrees to participate in the testing of the doctor's latest experiment: a prosthetic mask molded from the facial characteristics of a surrogate donor. Now liberated by a sense of faceless anonymity and relieved of personal and professional entanglements, Okuyama takes up residence at a modest boarding house and begins to test the limits of his traceless identity.

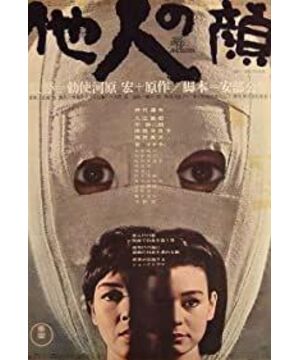

Marking Hiroshi Teshigahara's third adaptation of novels by modernist author Kobo Abe, The Face of Another is a highly stylized, psychologically dense, and provocative exposition on identity, persona, freedom, and intimacy. From the opening sequences of isolated anatomy, Teshigahara establishes the fractured tone of the film's narrative. Surreal, aesthetically formalized shots of the oppressive prosthetic laboratory underscore the atemporal and geographically indeterminate nature of the universal parable. (Note the disjunctive effect of freeze-frames, muted ambient sounds, and cultural polyphony of the doctor and patient meetings at a German pub-themed bar that further contribute to a sense of existential ambiguity and pluralism). The intercutting parallel,elliptical narrative of a facially scarred young woman (Miki Irie) - whose character introduction is intriguingly accomplished through a wipe-cut (and therefore, may only exist as a figment of Okuyama's imagination) - creates, not only a pervasive sense of alienation, but also betrays the unsympathetic protagonist's internal chaos and capacity for emotional violence. Combining striking, elegantly composed visuals with innately humanist themes of connection and identity, Teshigahara composes a haunting, cautionary fairytale of masquerade and revelation, defect and vanity, impersonation and self-discovery.but also betrays the unsympathetic protagonist's internal chaos and capacity for emotional violence. Combining striking, elegantly composed visuals with innately humanist themes of connection and identity, Teshigahara composes a haunting, cautionary fairytale of masquerade and revelation, defect and vanity, impersonation and self-discovery .but also betrays the unsympathetic protagonist's internal chaos and capacity for emotional violence. Combining striking, elegantly composed visuals with innately humanist themes of connection and identity, Teshigahara composes a haunting, cautionary fairytale of masquerade and revelation, defect and vanity, impersonation and self-discovery .

View more about The Face of Another reviews