The screenwriter described how this noble world fell under the temptation of money and extravagance. This expressive technique is full of power, and at the same time it inevitably shows the color of classical tragedy.

| Godfrey Cheshire

February 12, 2019 |

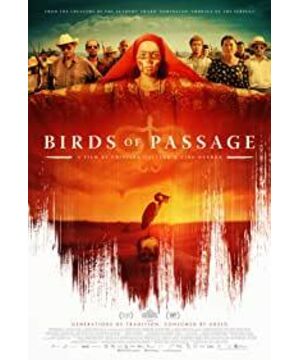

When Cristina Gallego and Ciro Guerra’s gripping, brilliantly mounted drama “Birds of Passage” (Spanish title: “Pájaros de Verano”) opens, we could almost be watching an ethnographic documentary. It’s the late 1960s and we’re observing a family from the indigenous Wayúu people in a remote, arid stretch of northern Colombia. A girl named Zaida (Natalia Reyes) has just completed her ritual period of isolation and her people are celebrating her emergence, which symbolizes her readiness for marriage. And that prospect looms up almost immediately with the announcement by Rapayet (José Acosta), a handsome guy from a neighboring family, that he wants her as his wife.

Zaida’s mother, Ursula (Carmiña Martínez), this family’s very imposing matriarch, seems suspicious of Rapayet as soon as makes his intentions known. She decrees a dowry that she seems to assume is way beyond the man’s means; it includes scores of goats and cows – the mainstays of Wayúu subsistence – as well as some valuable necklaces. It’s not long, though, before he returns with all the dowry items in tow. The way he enriched himself enough to afford his pretty and pricey bride is where the film’s crime story begins.

Much later in the tale, a woman from another Wayúu family notes that over the centuries her people have fended off pirates, the English, the Spanish and various Colombian governments trying to control them. They are very tradition-bound folks; they believe in ghosts, magic talismans and communications with the dead, and their paramount value is honor. Yet by the time the remark about their history is made, it carries a bitter irony, because the Wayúus’ way of life has been upended by a new enemy: lust after the riches that come from dealing marijuana.

Rapayet’s entry to the business happens when he overhears a shop owner say that some young, long-haired Peace Corps volunteers, who are in Colombia to combat the threat of Communism, are looking for some pot. Rapayet and his best friend, a high-spirited black guy named Moisés (Jhon Narváez), know a source up in the mountains, and soon they are making huge wads of cash delivering big bales of the weed to gringo drug runners who fly and in out on small planes.

But the operation doesn’t run smoothly for long. One day, the hot-tempered Moisés thinks he sees evidence that the gringos are betraying them by also dealing with some of their competitors, so he whips out a pistol and kills two of them. The murders are anathema to the Wayúu, and Rapayet’s family demands he execute Moisés.

“Birds of Passage” is based on actual events from the 1960s-'80s and is told in four roughly half-hour chapters, followed by a short epilogue. Co-directors Gallegos and Guerra previously made the Oscar-nominated “Embrace of the Serpent” (she produced and he directed), which depicts the interaction over several decades between indigenous people, including a formidable shaman, and Europeans. Although reviewers used the term “psychedelic” to describe that film’s imaginative style, it examined important issues in Colombian cultural history from an informed and committed Colombian perspective.

“Birds of Passage” does much the same. Its subject is the “Bonanza Marimbera,” the era when people in the Guajira region of northern Colombia – both Wayúu and others – became involved in drug smuggling, which in subsequent decades would be the source of much domestic trouble and international infamy for Colombia, and also, more lately, fodder for big-budget entertainments made mostly by non-Colombians. In interviews, Gallego and Guerra have rightly questioned the “exploitative” nature of shows like “Narcos” that offer glorifying portraits of mass murderers like Pablo Escobar.

Their film also concerns the drug trade, reaching back to its modern origins, and it deals with the violence that destroyed many lives, families and communities. Yet it skirts Hollywood-style sensationalism in several ways. For one, the filmmakers generally avoid direct, up-close depictions of violence. Sometimes we see only its results: bloody bodies lying in the middle of a road, for example. And in the story’s final act, when two families engage in a war with military-scale manpower and weapons, we see the confrontation mainly in a single searing long shot.

Gallego and Guerra also humanize their characters via their efforts to portray their culture accurately. The actors who play Rapayet, Ursula and Zaida, professionals who do excellent work, are surrounded by faces that clearly belong to this place; the filmmakers also made their crew 30 percent Wayúu to help assure the authenticity of the film’s details. And the sense that the portrayal of this community is exacting as well as flavorful comes not only from the documentary-like visual approach and Leonardo Heiblum’s evocative score, but also in the story’s elements of magical realism, which of course reflects the influence of Gabriel García Márquez, whose maternal family was Wayúu and whose “One Hundred Years of Solitude” includes numerous Wayúu influences.

Those literary elements are skillfully woven into the script by Maria Camila Arias and Jacques Toulemonde, which starts off in a world that may be poor and disadvantaged in many ways but that also has traditions of sustaining simplicity and integrity. The screenwriters’ way of describing this world’s fall from grace due to the lures of money and luxury has the power and inevitability of classic tragedy. It could be Greek or Shakespearean, though it is palpably modern and Colombian.

The translation of this film review can be viewed on the Martian Translator website. If there are any inaccuracies in the translation, please point it out, thank you!

Interpreter: Selling little matches for girls.

Proofreading: Thibault

View more about Birds of Passage reviews