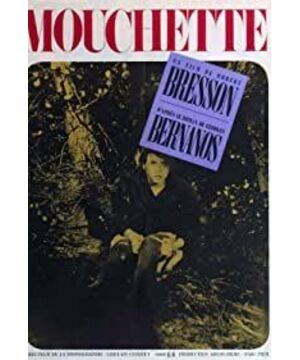

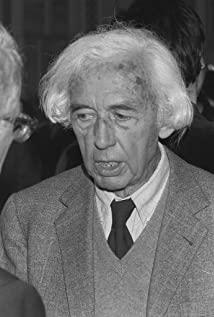

Robert Bresson has not many works. As a director, he only left 13 feature films and one short film. But in addition to being known by the world, the masters of film are also heroes and heroes: "Bresson is to French film what Mozart is to Austrian music, and Dostoyevsky is to Russian literature" (Jean- Luc Godard); Tarkovsky also listed his "Diary of a Country Priest" and "Muchette" as his top ten film history.

"Muchette", as his work in the mid to late 1960s, turns the lens to the confusion and suffering of young people in modern society. The certain degree of pessimism in the film is a kind of introspection of the director's own Christian values. And this kind of examination from the outside to the inside of the characters undoubtedly further consolidated his film writing.

Stylized presentation: Bresson-style film writing

It can be said that Bresson's work sequence has his consistent aesthetic pursuit. His rigorous and demanding films show internal consistency and a persistent individualistic worldview. [ [1] ] He invented and applied his "film writing theory", which is different from "cinema" (ordinary film production), and he prefers to call his work "cinematography" (writing through film). He believes that film production is a drama of photography, while film writing creates a new form of writing, through editing, creating a work of art composed of dynamic pictures and sounds. And given it several core concepts from camera, sound, picture to actors.

One of the most eye-catching is his "model" saying that he rejects any performance traces of actors, and he prefers to use non-professional actors. When the actor's emotions are all exhausted, it is the best performance state he wants. And this state is more like a subconscious exposure, without extra feelings. The audience only needs the close-ups from the outside and the sudden cuts of Bresson interspersed during the period, the short use of scenes, the brisk advance or pull of the camera, and the condensed sound track, which allows the audience to gain insight into the characters through this series of actions. Inner state, and those mysterious emotions. In "Diary of a Country Pastor", we seem to be unable to see any facial emotions of the protagonist. For this reason, Bazin pointed out that Bresson, like Delaire, naturally loves the most textured facial features, precisely because it is not a performance at all, but a unique imprint of a person, the most visible trace of the soul: various facial expressions. All are sublimated into symbols. What he draws our attention to is not psychology, but the physiognomy of existence. [ [2] ] For this reason, this rejection of dramatic performance instead allows the audience to focus on the voice of soul in the priest's monologue.

Another typical feature of Bresson’s films is that he adds a sense of continuous and gradual progress to the structure. That subtle change is more like a ritual repetition, clever for the actions that recur in daily life. The group enters the plot, giving people a constant accumulation of emotions, and subtly realizing the destiny of the characters. At the same time, it is worth noting that this kind of repetition deliberately deviates from the dramatic technique, because the events are not arranged according to the laws that the development of emotions will ultimately satisfy the spirit. The continuity between events is more of a necessity in accident. The concatenation of unrelated actions and coincidental events. Every moment, like every shot, has its own destiny and freedom. [ [3] ] In the following discussion, the author will also further analyze the emotional writing of the characters behind this repetitive action in "Muchette".

Variations on Bernanos' Texts: From "Diary of a Country Priest" to "Muchette"

"The torrent of speech does not damage a film. This is a matter of type, not quantity." [ [4] ] When it comes to the handling of monologues in literary adaptations, Bresson wrote in his "Notes on Film Writing" Said like this. As an excellent literary work, George Bernanos's "Diary of a Country Priest" is a school of its own. If you look at the video adaptation of Bresson at first glance, it is easy to think of it as a silent film full of subtitles. In Krakauer’s words, it must be classified as a non-cinematic adaptation. [ [5] ] However, after Bazin read the "Diary" in detail, he discovered that Bresson had actually used the film medium to "faithfully" transfer the formal characteristics of the original diary novel to the screen, that is, using sound and picture pairs. To expand the confrontation between subjective and objective in the original work, the style of the film is precisely the inconsistency of sentences and images. It can be said that this is Bresson's intention to take the completely opposite approach. Compared with the novel, the film is more "literary", and the novel is full of concrete images. Through this alternate treatment of literary and realism, the strictest aesthetic abstraction that abandons expressionism is achieved. This approach, through seemingly denial, actually reforms the expressiveness of the film. That is, from respecting the original text to create a dialectical element of style [ [6] ]

In addition to the form and style involved in the novel "The Diary of a Country Priest", the theme of the film is more in line with Bresson's pursuit of religious themes and human suffering. Suffering seems to be a metaphor that human beings cannot break free. Driven by desire and reality, it is difficult for human beings to cross this inevitable road. Only by immersion or resistance can salvation be achieved.

Bernanos was in the Spanish war period when he was creating "Muchette the Girl". In an interview with reporters, he said that he saw the poor people sandwiched between armed men. The Spanish that they carried was the most important. The dignity in the cruel suffering touched him. "Tomorrow they will be shot. This is the only thing they can expect. These poor people cannot understand this terrible game that involves their lives, and I am shocked by this." [ [7] ] Bernanos transplanted what he saw into the story of a little girl who was persecuted by poverty and injustice.

We did not see any temporal references in Bresson's films. However, looking back at the time when the film was shot in 1966, it is not difficult to speculate that Bresson chose to adapt the original intention of "Muchette the Girl", which was an allusion to the Vietnam War at that time. Bresson did not add what he saw and heard in the 1960s into the film, but was loyal to the text of the novel, unlike the use of large inner monologues in the previous works, but as much as possible to restore Mouchet’s place. This kind of treatment is not the director’s evasion of reality, but his perfect inheritance of the original spirit, using the ambiguity of the text to give the audience more imagination.

All of Muschett’s lines of action mainly revolve around the three points of home/school/wood. The church and the tavern playground are the key transitions, that is, to examine his heart through the external actions of Muschett. Bresson also fully excavated various objects in the background of nature: a plastic basket, Mouchet's Eugene shoes, some washing liquid in the grocery store, a kettle that is boiling water, a coffee stirrer, and an inconspicuous TV somewhere. machine. These things seemed to have life, silently witnessing everything around Muchet. It is worth mentioning that at the beginning of the film, Bresson arranged for Mouchet's mother to sit on a chair. She was in tears, as if she had a premonition of what her departure would trigger. After the mother's monologue was over, she turned and left, leaving behind a fixed long shot of the chair, time stagnated, and started rolling the subtitles. The beginning of the suffering has already been interpreted with the help of things.

The end of suffering and relief: Muchet's three tears and suicide

Bresson is good at portraying sentimental people struggling in a hostile world. In "Donkey Batsa" (1966), Mary was stripped naked and beaten to death by a bad boy; "Tender Woman" (1969), "Probably the Devil" (1977), including the protagonist in "Muchette" all committed suicide end.

If the film text is carefully sorted and divided, the dilemmas that Muschett faces in different fields are fully presented in the film. Regardless of the ending setting of the original book, Bresson, with the help of Mouchet's three tears, concisely and not simply led the end of Mouchet's miserable life to a fateful destination: suicide.

As a public place for collective activities, the school should be a place where Muschett feels warm, but here she is as sensitive and suspicious as a hedgehog. The teacher didn't like her, she could find it when she walked into the classroom with a piercing noise wearing wooden shoes of two sizes. When the teacher saw that the students were singing chants, and she was the only one who was silent, she forced her head to the side of the piano. Constantly singing out of tune, she ended this passage with tears. The tears here are still Bressonian, without any emotion. We can't read through more facial information to understand whether Muschett is ashamed or resentful of his surroundings. Tears are just an action, a verb, and it reinforces Muchet's loneliness in public places.

What brings a touch of comfort to this sense of loneliness is a key scene that Bresson added to the novel, the plot of Muschett playing with a bumper car in an amusement park. This is also one of the few tender moments in the whole film. In the bumper car collision, Muchet, who was only 14 years old, "touched" love. The rare brisk music in the video is intertwined with the sound of you hitting me and I hitting you in the bumper car. Walking out of the playground, Muschett took the initiative to smile at the boy for the first time, and was slapped in public by the alcoholic father beside him. Muschett’s self-esteem and adolescent girl’s ignorant heart were slapped and shoved. Deprived completely. Sitting back in the chair, Muschett couldn't help crying. For the first time in school, the tears this time had a more obvious emotional direction, and this emotion was also made by the audience through this series of actions. Express the inner words of the characters.

Muchet’s third tear was a plot paragraph at home. After being violated by the hunter Assen in the woods, Muschett, who lost his virginity, returned home the next day to help his mother feed milk to his infant brother. Here, Bresson arranged two consecutive scenes of Mouchet's tears (feeding brother milk and waking up from sleep), because it is a continuous action that also occurs in the same place at the same time, it can be temporarily combined. In a confined space at home, Muschett assumes the role of a mother. She boils water, makes coffee, changes diapers for her brother, and looks after her sick mother. Also in front of her mother, she was able to relax temporarily, calling her mother softly, kissing her mother's hand, and fetching wine for her mother. To some extent, Muchet's gaze at his mother's behavior was looking for a touch of humanity. It can be said that the femininity was initially hidden in Muschett, and it gradually awakened after being teased by neighbor boys, playing bumper cars in the playground, having sex with hunter Assen, and feeding his younger brother.

She didn't understand the true meaning of "slut". When Assen was suffering from epilepsy, Muschett acted like a mother to gently lift the fallen Assen's head, and hummed softly the holy spirit he had learned from school. Song, the warmth of this moment formed a great contrast with the reality, but it was reasonable. Therefore, when his mother died of illness, the bad guys from the neighbouring bakery came to check his breath when he found something abnormal on Muschett's body. Muschett turned a blind eye to it. "I'm Mr. Assen's woman" she even said to Mr. Mason's wife, the policeman.

The repetitive action of tears drew Muschett's emotions into resistance. When she met the last woman, she officially faced the topic of death for the first time. The kind-hearted woman opened the topic of death around the death of Muschett’s mother, "Will the dead become like gods?" "Do you know the mood of the deceased?" The topic of death is too heavy and complicated. As for Muschett, he also looked back with those malicious eyes that were sinful in the eyes of outsiders.

Muschett returned to the countryside with the exquisite shroud and the beautiful transparent linen dress that the woman gave. But I met the scene of hunters rounding up hares. The hunting behavior of the hunter spent a lot of pen and ink in the official opening of the film. In the opening scene, Bresson kept using Assen's left eye close-up to describe the hunting behavior of the hunter, cutting out the shots constantly, and repeating the close-ups of the eyes. Switching to substitute the audience into the emotions worrying about the fate of the animals. The scenes of the hare running at the end and the final hunting are repeated in opposite directions. The main perspective here is Muschett himself, rather than the audience and the hunter Assen at the opening. Muschett came to the place where the rabbit fell to the ground. The camera didn't explain whether Muschett saw a rabbit, but all the bedding in front of it pointed directly to it.

"Only the word'death' lingered in her ear, as if it was the first time she heard it. Yesterday, the word was meaningless to her, empty and void, but it made her faintly scared, very vague, and very strange. Certainly , a very passive kind of fear." [ [8] ] Bernanos used an objective tone in the original work to portray Muschett’s thinking about death, while Bresson used the idea of letting everyone around him All her actions led her to the line of action against death. This is the case with repeated hunting at the beginning and end. Finally, half wrapped in the linen dress, she rolled down the slope like a bucket. During the period, she thought about giving up suicide. For this reason, the director arranged for the trailer sound to enter the painting first, and Muschett followed the sound and stretched out his hand. As the trailer walked away, Muschett rolled down the slope like a bucket for the second time, and finally for the third time, we learned the result from the sound of falling water and the linen skirt hung by the pool. In the end, Bresson presented the middle section of the roll down the slope in front of the screen. This treatment was undoubtedly warm, and he used the last trace of gentleness to fight against this hopeless society.

Perhaps it really responded to Bresson’s words, “Death is not the doomed fate of suffering, but the end of suffering and liberation.” [ [9] ] Mouchet used the act of "suicide" to confront the people around him. And the restraints imposed on her by society. And the era represented by Muschett existed especially as a rebel.

[1] [United States] David Bodwell and Christine Thompson; translated by Fan Bei, World Film History (Second Edition), Peking University Press, February 2014, p.555.

[2] [French] By Andre Bazin; Translated by Cui Junyan, What is a movie? Beijing: The Commercial Press, 2016, page 110.

[3] Same as 2, pages 111 and 112.

[4] [French] Robert Bresson; Translated by Zhang Xinmu, Notes on Film Writing, Nanjing University Press, p. 25.

[5] [Germany] Siegfried Krakauer; Translated by Shao Mujun, The Nature of Film-The Restoration of Material Reality, Published by China Film Publishing House, first printed in October 1981, p. 307.

[6] Same as 2, p. 105 and p. 108.

[7] Roland Barthes; Gu Lingyuan, the master talks about Bresson's film, contemporary film, 2001 01

[8] [French] George Bernanos, translated by Wang Jiying, Girl Muschett, Shanghai Literature and Art Publishing House, April 2011, p.129.

[9] Same as 2, page 112.

View more about Mouchette reviews