The movie is based on the 1995 novel by Anna Quindlen about a New York magazine writer whose father is “Mr. American Literature” and whose mother seems to have been shaped by the same forces that generated Martha Stewart's hallucinations. Ellen (Renee Zellweger) is bright and pretty but with a subtle wounded look: She has that way of signaling that she's been hurt and expects to be hurt again.

She comes home to upstate New York for a surprise birthday party for her father, a professor named George (William Hurt), and is not surprised to see her mother, Kate (Meryl Streep), prancing around the house dressed like Dorothy in “The Wizard of Oz." Yes, it's a costume party, but Kate is the kind of woman who can find costumes like that right in her own closet. Eventually Ellen gets a chance to ask her dad about her latest magazine article, which he has read and, “writer to writer,” thinks should be “more muscular.” Later he muses, “When I was 20 and working at the New Yorker, I would spend a whole day working on a single sentence.” That's the kind of statement that deserves pity rather than respect; if it is true, then to meet his deadlines he must have had to dash off his other sentences in heedless haste.Ellen should be able to feel a certain contempt for her father for even using such a ploy, but she is blinded by his tweeds, his National Book Award, his seminars, his whole edifice of importance. He thinks he's a big shot, and she buys it.

Ellen's hurt, we see, comes because her father, whom she admires, does not sufficiently show his love for her--while her mother, of whom she disapproves, has a love that is therefore unwelcome. All of this begins to matter in the next months, as it develops that Kate has cancer, and George wants his daughter to move back home and take care of her.

But ... I have a career, Ellen argues. “You can work as a free-lancer from home,” the professor says, clearly not convinced that whatever his daughter has can be described as a career. He, of course, is too busy with midterms to take care of Kate. The family's younger brother, Brian (Tom Everett Scott), must stay in school. Yes, a nurse could be hired, but the professor doesn't want a nurse poking around the house and disturbing his routine. Kate herself doesn't want Ellen to stay, but wasn't consulted (by her husband or her daughter) about the decision.

As autumn winds down into winter, Ellen coexists in the house with a mother who is clearly demented in the area of domestic activities. She belongs to a local group named the Minnies, who decorate Christmas trees with the fury of beavers rebuilding a dam. The luncheon meetings of the Minnies could be photographed for layouts in food magazines, and of course the Minnies cook everything themselves. When Ellen breaks a piece of Kate's china, Kate asks her to save the pieces because she can use them in her mosaic table. Ellen finally tells Kate she thinks the Minnies are like a cult group.

George, on the other hand, throws his daughter a bone; he asks her to write an introduction to his collected essays. She is flattered, although a little wounded that he then immediately asks her, in more or less the same spirit, to launder some shirts.

As winter unfolds and Kate's illness grows more severe, Ellen begins to suspect things about her father, and her mother observes this and finally tells her: “There's nothing that you know about your father that I don't know--and better." And we see that the buried story of the movie is the hurt Kate has borne all these years over the way her daughter's love was quietly directed away from her.

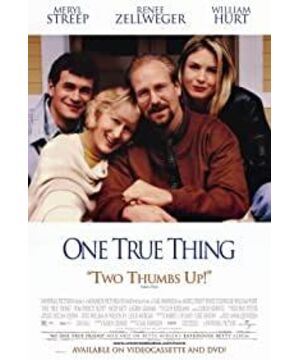

It is the craftsmanship that elevates “One True Thing” above the level of a soaper. The director, Carl Franklin (“One False Move”), goes not for big melodramatic revelations but for the accumulation of emotional investments. Hurt and Streep are so well cast they're able to overcome the generic natures of their roles and make them particular people. And Renee Zellweger, as Streep observed at the Telluride Film Festival, is able to create a place for herself and work inside it, not acting so much as fiercely possessing her character. The movie's lesson is that we go through life telling ourselves a story about our childhood and our parents, but we are the authors of that story, and it is less fact than fiction.

View more about One True Thing reviews