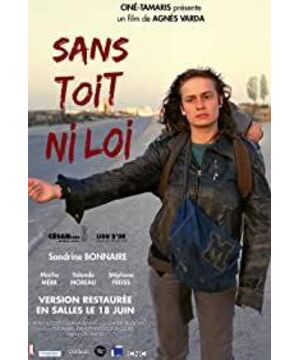

Games of the form do not appear in every movie belonging to this mode, but it does appear repeatedly. A notable example is Anesvarda's "Wandering Girl". The film consists of a typical art film scene: an unexplainable psychological crisis causes a young woman to quit her job as a secretary and live a wandering life in Montpellier. Her travels are presented more or less in chronological order. She connects various characters in adjacent villages, then indulges in alcoholism, and then runs out of life. The film begins with the discovery of her frozen corpse, and then presupposes a structure to question her history after death. Those who have met Mona brought out their flashbacks, showing Mona's last week of life. But in addition to the inevitable question-"What caused her death?", the film added another question, "Who are these witnesses telling their stories?"

At the death scene, it was the police who asked the witnesses. people. This scene is customary and coherent, except for a strange composition that may pause the alert audience. After Mona’s body was removed, a female voice was suddenly inserted on the beach and sea scenes: “People she met recently have remembered her... They talked about her, but But I don’t know that she is dead.’ If it’s Varda’s voice, as I think, we are vacillating between objectivity, subjectivity (how people remember Mona), and the author’s intervention. It’s a The characteristics of art film narration. When announcing that “these witnesses helped me tell me about the last week of her last winter”, the commentary established some rather contradictory basic rules. Those who remember Mona may Talk to each other, just like the conversation scenes in a regular movie, and these will continue into the flashback. This is a "Citizen Kane"-style choice. Another option is that the witness may explicitly face Photography and lens testimony, answering questions from outside the screen in the style of a documentary. Hou Xiaoxian pursued this strategy in his biographical film "A Dream of Life". However, "The Wandering Girl" turned out to use both schemes. And he also introduced other transformations. Witnessing people "helping" filmmakers "tell" Mona's story in many disturbing ways.

The first flashback of "The Wandering Girl" was introduced by some idle boys who reminisced about Mona on the beach; we were just eavesdropping on their comments about her. Later, at a truck gas station, a driver told another person that he let her ride, and then a garage owner told another person that he hired her. But there has been an adjustment here: the person who is the subject of the truck driver’s story is completely visible, and the first shot of the garage owner who is talking about Mona starts with a reversed angle composition, so we only Can see the shoulders of the narrated subject. When we left the flashback, he was still talking, but he was facing an invisible listener. In a regular movie, such a transformation may only be used to emphasize the testimony of the owner of the garage, but here they are slowly entering a style of narrative uncertainty. Soon afterwards, the maid Yolan De stopped cleaning and turned to face us, telling how to break into the villa guarded by her uncle. This monologue does not tell us anything about Mona. It is more suitable for telling Yolande's idle boyfriend Paul, rather than any other person inside or outside of a fictional story. In the memory, we can think that this is the case at this moment. At that time Yolande

was talking to Paul. Paul may be outside the painting (he sneaked in and was outside the household), but this is by no means certain. of. We have never seen who she is talking to. This fact fundamentally breaks the internal norms established so far. Later, when Yolande met Paul at the villa, she spoke to the camera lens again, and now she confessed that she was moved by the sight she saw. She saw Mona and another wanderer, David curled up. Sleep together. This time, it is completely certain that this is a self-talk. From an objective description of an unfeeling male witness to a subjective monologue, a woman spontaneously tells us her desire for love and partner.

Just like learning Yoland, the hippie David soon got a telling play. He squatted in the carriage of a truck, telling how happy they were when Mona got the marijuana. As far as the story world is concerned, his statement digs into the corner of Yoland's romantic thoughts; the relationship between him and Mona is nothing more than a reaction after taking psychedelics. In the narrative, all the possibilities seem to be gone. So is he monologue? Unlike Yoland, he doesn't look at us directly; his eyes move sharply from side to side. So is he talking to other people? No one was visible, and he was still talking when the train was leaving.

In all these scenes, the cues of the narrative arrangement are contradictory, and these cues hinder any coherent understanding of the environment of the characters in these narration scenes. As the film continues to develop, these inserted memories continue to oscillate between these possibilities, mixed with other changes. Sometimes repetition confirms inferences we might have made earlier, such as when Yolande confessed to the camera for the last time before leaving the storyline; she was the only person who was given three private monologues. In other cases, the characters are either speaking to the camera about Mona's behavior, or passing the camera, or facing another person in the scene, or maybe there is some kind of mixture of all possibilities. Perhaps the most disturbing thing is that at certain moments Mona's eyes are fixed on the camera, and sometimes they stop, as if she was looking at us at the time. The narrative's determination to throw us off the balance to a real point is the scene of Asun, a migrant worker in Tunisia, where Mona's closest person just kissed her scarf and then looked at us in silence. At this purely symbolic moment, he didn't seem to react to anyone present, whether it was a character or a filmmaker.

At the end, Mona's wandering story still maintains its episodic character, and her motives are still a mystery. Our construction of the story of this art film is based on a series of judgments made by different characters about her. Up to now, it is still so in line with the convention. However, Anesvarda's handling of the ambiguity of the situation in which the characters tell the story also invites us to participate in the typical game of hesitation in form. Perhaps the vacillation of the onlookers at Mona's hasty glance can ultimately be attributed to the supreme control of the narrative over the original condition of the story. The voice-over commentary of the film method has been publicized very early, and it also contains a narrative paragraph. "I don't know much about her," the woman's voice said, "but in my opinion she came from the sea." At this time, we saw a shot of Mona striding out of the sea. This scene was ridden by bike. Witnessed by the boys. The beginning of the background story is a swing between objective presentation and frank author's imagination. Maybe everything next. Even hard materials created by local customs, dialects, and non-professional actors. Will be understood as the creative power subordinate to the author's insight (not the implicit author, nor a "film narrator", but the person who makes the film for us).

This sharp film intersects with many other styles, especially the tracking lens composed of planes, which induces us to discover another "theme-variation" structure. A comprehensive analysis will also show how the formal play in the narratives of different narrators prevents us from constructing a complete mental profile of Mona. Instead, formal games turn us to a productive or unproductive life comparison of the characters she comes into contact with. A dilemma in the theme of the film is how to reconcile total freedom with the danger of being alone. And this tension is released among these bystanders, who admire, criticize, or worry about the homeless and lawless Mona. In addition, our consideration of the theme-extracted from our experience of the film, should be balanced with how we understand the narrative. This understanding is a little bit of mixed signals and follow the curve. Curvy path. "The Wandering Girl" is full of unease about Mona's choice, and one of the most important parts is the product of the ambiguous narrative.

········

View more about Vagabond reviews