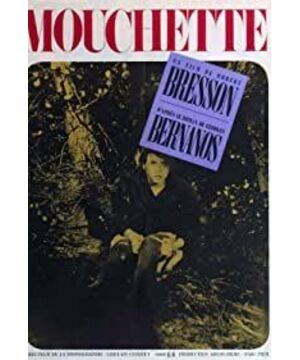

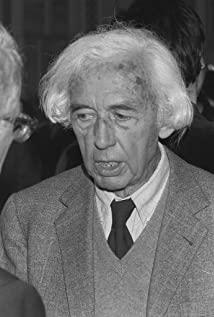

"Muchette" continues Bresson's consistent aesthetic style, restrained and concise, allowing the film itself to appear naturally. Bresson is perhaps the most adept at using omission and repetition as a film writer. With a pair of silent and mourning hands (like those under his lens), he writes on the screen the pain of the individual, the struggle of human nature, and the absurdity of destiny. , Full of religious colors of asceticism and humanitarian philosophical thinking.

Muchet is the daughter of a poor family. Her mother is dyingly ill, her father and eldest brother sell alcohol and drink alcohol, and have a baby brother. Her family has become numb to the daily misfortunes, self-deceiving and reluctantly, indulging in Marcel-style "contractures", poverty, disappointment, indifference and violence secrete a kind of shell, which slowly hardens. Become a cage to imprison them.

But Muschett is different, perhaps because of her youthful sharpness and lonely keenness, she has always stared at her life like an outsider. She understands her limitations in material survival, but she is also sensitive to her youthful and ignorant desire for spiritual survival in the depths of her heart. So she was angry, surly, and sometimes docile. She is looking forward to love and protection, hoping that the spirit can surpass the material and bring her comfort. So she inevitably struggled to grow up in the contradiction between the identity of the two identities (the poor and the young girl)-these are also the two narrative arcs centered on Muchet in the film.

In "Muchette", Bresson, in addition to omitting language, music, and plot with a concise style throughout, laid a Brecht-style alienation and alienation to the whole film, it is particularly noteworthy It is his concern for repeated use and objects. Objects cannot express themselves, but their silence gives them charming simplicity and association. So Bresson focused his close-ups on various objects, created a series of motifs, and repeatedly described them to reveal the symbols and metaphors behind them. Suddenly, objects without emotion gain the freedom of expression in our vivid and expansive consciousness, establishing a kind of life-like existence. Repetition is a kind of rhetoric, and the object becomes a kind of language, creating a larger blank space in the movie, and we need more conscious awareness to fill the gaps he alluded to.

The first is leather shoes and mud. The first description of Muschett’s leather shoes happened when she was going to school. In the silent classroom, we first heard a series of procrastinating, stiff and even a little piercing “click”, and then we moved down the camera and looked at it. He was wearing Muchet's big abrupt, torn and muddy leather shoes. Combined with the teacher's contemptuous look at Muschett in the next scene, we know that Muschett, who is too poor to deal with himself, often suffers from the cold violence of others. Afterwards, she took off her shoes as soon as she got home, which meant that she could breathe for a while at home, without having to bear her ridiculing eyes. After that, the shoes appeared in the rainy night. Muschett lost the shoes in the heavy rain, and Yasen helped her find them. The narrative lines of the two identities merged here. For the first time, Muschett felt the kindness and protection of a man to him. Perhaps she was also attracted by Yasen, a lonely heroic character full of primitive wildness because of her rebellious and wild nature. In short, "love" began to sprout.

The soil is also a recurring image. After school, Muschett hid in the grass and threw dirt on his classmates. In the Kurischoff-style montage, we saw the dirt hitting other girls’ clothes, bags and hair for the first time, and the second time. Smashed on the perfume. The first time, Muschet hated the injustice of life, and the second time, she yearned for objects that represent beauty and femininity. She saw the pure white underwear exposed by the girl when she played, and arrogantly responded with contempt for the male classmate's sexual harassment, and even had a first love in the amusement park. Her feminine consciousness gradually awakened, but she was frustrated by the inferiority and embarrassment that the girl's image could not show under the poverty and greasy dust, so she took revenge within her capacity to this hostile world.

The combination of mud and shoes, that is, Muschet deliberately stepped on the slimy quagmire with his feet, appeared twice before and after. The first time before the steps of the church, and the second time towards the end, Muschett heard the grandmother say: "I love the dead and I understand them very well." He began to rub the mud on the shoes hard on the carpet. . Both of these actions are connected with religious things. In front of the cross by the bedside of the dead mother, Muschett finally ceased to be silent, and resisted his father's insults for the first time. Although Muchet is in a Christian family, she does not believe in God. If there is a god, why is she still so miserable? She expresses resentment in a way that defiles the sacred, and at the same time tries to get rid of the "stickiness" that drags her into the current situation and prevents her from flying to a free life.

She responded rudely to the world’s difficulties. She threw the dishcloth into the sink while she was working, and threw the croissant off after being insulted. Her rudeness may not only be due to lack of education, but a defensive response to the threats of others and inner self. Only by showing extreme arrogance and carelessness can she offset her inner inferiority and protect herself from hypocrisy. Only by the violation of others can we get rid of the sense of shame and no longer arouse the hatred of ourselves.

In addition to these recurring objects in close-ups, there are many other visual motifs with symbolic meaning. For example, the image of fire that played an important role in the dark and stormy night. At first, when Yasen took her to the thatched house to avoid the rain, he tried to put out the fire in order to cover up the traces. We saw a cluster of flames trembling slightly in the dark, and then turned into ashes in the cold light of the flashlight. After they arrived at Yasen's wooden house, Yasen lit the candle on the table, and the room was suddenly illuminated. Then he lit a fire, this time the fire was blazing bright and unscrupulous. In the fixed close-up of Muschett's hands struggling and finally holding Yasen, the fire behind them burned vigorously. Fire is a burning desire, a primitive impulse for life, and even more dangerous violence and dedication.

The storm at the climax, with a few words, decided the fate of Muschett. Yasen said to Muschett, "Listen to this storm." So they listened in silence to the roar outside the house. But when Muschett tried to explain to his mother and guard Matthew what happened this night, their reaction was confusing. The mother said, "Storm? What storm? My poor child." Matthew said, "Storm? You are too fragile to be afraid of this light rain? The storm's "absence" in their contemptuous tone represents Mouchet’s cut off communication channels. She can’t express herself to the world because no one wants to hear her. Tempest is also a Rashomon, and we and Mouchet are in a very restrictive narrative perspective at the same time. We can only imagine what is happening. And Muschett doesn’t seem to understand what kind of changes she has undergone. She replied: “There is a storm, isn’t it? ". Maybe she feels fear and shame about the "stormy" violence and coercion, maybe she is being burned by the "stormy" love desire, but no matter what, she needs to talk. She desperately looks for an exit, trying to fall It was a downpour from my heart. But my mother watched her tears, but she didn't ask anything. When Muschett finally gathered the courage and tried to tell his mother, he was interrupted by his brother's crying again. Muschett comforted her. Good brother, hid good wine, and tried to talk again, but my mother was dead. Her death forced Muschett to undergo a rapid change of identity overnight: from a girl to a woman, and then to the brother’s "mother" From today onwards, she will take all family obligations as a matter of course. She will bear the abuse and humiliation from the society, just because she is a "woman" and the daughter of a poor family. The world has blocked everyone's ears. Cut off her throat. Even if she doesn’t care about others’ eyes or the gaze of others, she can’t lose her freedom. So, "When she finally sorts out her clues, she eagerly wants to tell others the secret of her missing love At that time, she thought of death. "

On the way to death, Muschett saw the hares hunted by the men desperately running around, but in the end they could not escape the fate of tragic death. Corresponding to the wild birds trapped in the film's opening, Bresson used a series of multi-angle and gradually enlarged scenes to prolong the animals' struggle time and magnify their weakness. The babies in the story are like these animals, unable to express and at the mercy of others. Life is so absurd and empty. The same is true for Muschett, the world is dominated by fate, full of mysterious and impermanent changes. In the classroom, the teacher pushed her out of the team and pressed her head to the piano; at the door of the church, her father pushed her into the door, Muschett rushed to the holy water altar and almost buried her head in. earthen jar. The symmetrical composition and movement of these two scenes convey the same fable: Destiny is like a torrent that envelops Muschett, forcing her to lower her head again and again.

But Muschett did not intend to succumb. She rolled down the hillside, chasing death. For the first time, she failed, and the cruel fate rejected her again. So she violently defies the will of fate, and she is determined to die. She rolled down again and again, and finally, the river gently accepted her. Sartre said: "Only our free choice can stop us. If we want to live, then we must decide to live." Death is the same. Bresson used a fixed lens to quietly wait for Mouchet's departure (for appearance), and cut the lens directly onto the ripples of the river. We heard the sound of falling water, but we were not able to witness Muchet's death with our own eyes. Just like this, Muschet disappeared in the gap where the lens broke. At this time, the sad music of the opening sounded again, so we know that in this unfinished line of poetry, in the absurdity of this existence, Muschett tightly grasped her shroud and finally gained freedom.

Bresson's "model" is different from the actors on the theater stage. They are restrained, silent, and their movements are subtle and slow. They let themselves cry, without making a sad expression. Without the auxiliary explanation of language and the emotional hint of the soundtrack, he uses repetition to slowly reveal the meaning, and uses omission to make the image and sound interact perfectly in the fracture and opposition, creating a hostile world without emotion.

The behavior of the character is usually shown as surging or pushing, and shown as throwing, lighting, or breaking. Bresson deliberately concealed information and focused our attention on behavior, because it was behavior that caused the destruction. In films such as "Muchette" and "Money", people are always opening and closing doors constantly, constantly picking up and putting down schoolbags, hip flasks and other objects, always accidentally knocking out bowls or cups. During this period, life has undergone ups and downs, ups and downs, and finally broken or destroyed.

His low shots, close-ups, jump cuts, carefully arranged sound elements and scene scheduling give the behavior a strange and static sense of ritual. It makes those who can't see their faces look like objects, exuding a kind of cold and true spiritual texture. Sometimes it seems absurd, but it is always powerful.

Bresson is like this, using his strong formalistic aesthetic style "centrifugal force" to block the audience from the screen, but at the same time it also gives the audience greater freedom. When we are not deprived of rationality and do not have to succumb to emotional blackmail, we look at things with more conscious eyes. Abbas said: "Great art is inspiring, so it needs some kind of intervention." Bresson also hoped that the audience would cooperate with him to fill the gaps he alluded to. So he evoked the echo with the blank, let us take the initiative to think about society and life with compassionate eyes, and pay attention to the destiny of individuals.

He subverted the formula and removed the dramatic elements, so that the purest essence of the film was revealed, and the poetic dwelling in the "silver screen". And we found our freedom in the incredible reality on the screen.

View more about Mouchette reviews