An auteur maudit of his time, German émigré Douglas Sirk's renown has been considerably reappraised with much admiration for his trademark disposition of light and color, the swelling watchability sublimated from its saccharine source material, aka. the often derogated melodrama, and affecting emotional flux elicited from his sharply tricked-out players (Rock Hudson is among the staple).

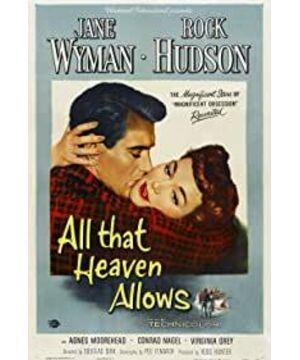

Sirk's second Wyman-Hudson vehicle, ALL THAT HEAVEN ALLOWS, is a lean, Technicolor-fueled, frippery-free, love-overcoming-moral-prejudice romantic drama, a middle-class suburban widow Cary Scott (Wyman) gallantly accepts the marriage proposal from her much younger boyfriend Ron Kirby (Hudson), who is hailed from a different class bracket and has no ambition in pursuing affluence. What transpires in the wake of her decision trenchantly discloses the selfishness, snobbery, myopia and hypocrisy inherently pertaining to the objectionable mindset of small-town bourgeoisie. On paper, the story sounds platitudinous, but Sirk's wow factor is, as always, his divine composition of the palette and setting, everything is undergone through a minutely preparatory process, from the impeccable cosmetic furnishing and elegant garbs of itsdramatis personae , to its almost storybook environs, however, to counterpoise the richness on one's eyes, Sirk is quite self-aware of not overreaching himself, ergo , the plot pans out in a reductive but expressively accurate manner, sansd evious routes, to sustain a vigorous lifeline that magically keeps a spectator rapt.

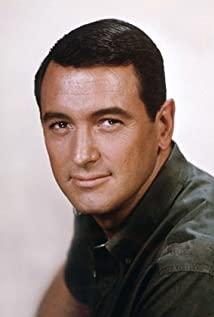

It goes without saying this approach often lives and dies with the performers, and in this case, it totally hits the bull-eye. Jane Wyman is a screen paragon who can yoke unperturbed grace with understated determination in a pinch, and step by step, Cary's liberation from those fetters chained to a lonesome widow is limned through her pitch-perfect, layered felicity that it hits every right spot to accompany a viewer's mirrored, visceral journey. Rock Hudson, a quintessential specimen of American masculinity and good looks, aptly elicits Ron's larger-than-life symbol of perfection but at the same time, conveys his vulnerability and misery with pinpricks of impatience and disappointment, which injects a more personal note to the character.

As regards the peripheral roles, Gloria Talbott and William Reynolds, who play Cary's college-age children, both stoutly take it to themselves as the cardinal negative force impeding their mother's new romance, with the former's talk-the-talk, walk-the-walk turnabout and the latter's sheer self-seeking callousness, god bless our offspring. But one's heart easily goes with a solicitous Agnes Moorehead, who is always a pleasant sight as Cary's matter-of-fact confidant and an effulgent Virginia Grey, radiating warmth even if she is not necessarily needed to do so.

Lastly, the purportedly compromised ending, stank with the inimical Catholic precept that one must suffer (both physically and mentally) plenty before finally gaining the reward, comes off as a fly in the ointment to wring a quasi-tearjerking effect, nonetheless, as vouched by Liszt's timelessly enchanting Consolation No. 3 in the beginning, ALL THAT HEAVEN ALLOWS oozes a vintage vitality in its most luscious taste, isn't that a delight?

referential films: Sirk's MAGNIFICENT OBSESSION (1954, 7.1/10), WRITTEN ON THE WIND (1956, 8.0/10); Rainer Werner Fassbinder's ALI: FEAR EATS THE SOUL (1974, 8.7/10); Todd Haynes FAR FROM HEAVEN (2002 , 9.2/10).

View more about All That Heaven Allows reviews