The heir to this tradition is the BBC Natural History Department established in 1957. The world’s first television department dedicated to recording nature has gone through several decades of broadcasting, black-and-white television, and color television. In the past three decades, the Ministry of Natural History has been able to explore subject matter, innovate in perspective, and improve effects. No one can beat it. On the other hand, the BBC filmmakers have a consistent positioning of themselves and their images-human and nature. This positioning has begun to take shape as early as the 1930s. In the 1930s images about the African wilderness, the American couple Martin and Ossa Johnson recorded their "expedition stories" about shooting animals. These hunting collections that will become the target of the public now satisfy the audience's pursuit of excitement and curiosity. . In the same era, the Englishman Cherry Gilton launched the prototype of "Frozen Planet": In his "An Adventure in Search of Laughter", Gilton rarely interferes with the protagonist of the film—— Most of the "performances" of penguins he called "little comedians" appeared in the background, and at most they waved their hands to imitate the naive attitude of "comedians". On today’s TV screens, we still see two distinct types of documentaries—one is similar to Hollywood "expedition films," in which people are natural participants and even conquerors, such as the Steve Irwin series; the other It follows a more pure recording style, where people are observers who do not appear on the camera or "accompaniers" who appear on the camera but do not act, such as the series of works by David Attenborough.

McLuhan believes that the media is an extension of the human body. Nature documentaries can be said to be the simplest embodiment of this media view. In the age of urbanization and digitization, these documentaries take on the task of extending the senses of dwelling animals to the limits of the wilderness. Every new technology introduction of BBC nature documentaries is almost for a revolution of the eyes: underwater cameras and infrared cameras help the eyes adapt to the deep sea and night; micro-shaped cameras bring the eyes into the grass and the ground; the realization of the camera on the back of the bird A bird’s-eye view in the true sense; a high-magnification lens focuses on the body of an insect; a satellite lens provides an astronaut’s field of view; thermal imaging provides a viper’s field of view. After all these technologies are mature, "Africa" brings us almost a "God perspective": from the outline of the African continent in space to the cilia on the arrow ant "space suit", you can have a panoramic view.

Technical perfection brings infinite possibilities to the perspective of documentaries. A natural drama like the hunting of sardines along the coast of South Africa has already been shown in "Blue Planet". It doesn't matter, let the whale be the protagonist in "Africa" and let the audience's eyes follow the turbulence of the giant whale. School of fish. The hatching of sea turtles in the same episode is also an old drama, but this time looking at the sea from behind the little sea turtle that broke out of the shell, the audience really realized what an "impossible task" is, just like in a first-person game. The camera guides the audience into the world view of the turtles and participates in the completion of the mission to the sea. This passage is a bit like the beginning of "Saving Private Ryan", but the same cruelty is reversed.

In "Africa", the extension of the senses is not limited to the eyes. What is amazing is the film's handling of sound. The BBC also made up for the shortcomings of human vision and hearing, and artificially strengthened the sound of the natural world. From the reverberation of the heavy blow of the giraffe duel to the sound of arrow ants, the sound we hear in the film is clearer than when we are actually in the wild, and the exaggerated sound effect effectively assists the dramatic effect of the lens. The sound of "Congo" is richer and more interesting. After all, in the rain forest, recording may be a more effective way of ecological recording than photography. It often confesses more species than the lens. (I hope the BBC will produce a nature tape with Edenburg's commentary.)

Some people would think that wild animals are ideal subjects for documentaries. After all, animals are not "pretentious", but they are not. In the presence of photographers and other staff, most wild animals will be emotionally stressed and behave unnaturally. To capture the "private life" of animals, the best way is to make the photographer and even the lens invisible. For this reason, various “spy” cameras were used in the BBC documentary: remote-controlled “stone cameras” mixed into the lions, “turtle cameras”, “crocodile cameras” and “dragonfly cameras” lurking in the wildebeest. Tiger’s "trunk camera", "log camera" and so on. Like infrared trigger cameras, these cameras can often help people obtain valuable ecological information. In the BBC film "Lost Land of the Tiger" filmed in 2010, a camera trap captured a tiger living on a hillside at an altitude of 4,000 meters in Bhutan. This discovery brought a glimmer of hope for the bleak survival prospects of tigers.

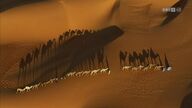

Another big problem in shooting wild animals is that the animals in the lens often do nothing. Finding the subject requires a wealth of experience and first-hand information. To capture a specific behavior requires both precision and luck. BBC nature documentaries often distort time through the combination of ultra-high-speed camera and time-lapse shooting, presenting natural time and space in the form of dramatic time and space, so that "boring nature" meets the "excellent" standard. As warm-blooded animals, our understanding of time is incompatible with warm-blooded animals. In their eyes, our lives may be unimaginably noisy. So in Attenborough’s "Snake", we see an African rock python flying by in time-lapse shooting for several weeks, and the predator lens that takes less than a second is fully visible through ultra-high-speed camera. Even being analyzed under an X-ray lens, such a technique is not uncommon in Planet Earth. Time-lapse shooting can be said to be another transformation of the human eye in the documentary, and the process that is imperceptible to the naked eye is shown under the time-lapse lens. Attenborough’s 1995 series "The Private Life of Plants" used this technique extensively to show the struggle between plants and the whole process of flowering within a few seconds. On the screen, it seems that all organisms become active like warm-blooded animals. But the function of time-lapse shooting does not stop there. In "Frozen Planet" and "Africa", the audience witnessed the "vicissitudes of life"-like landform changes in one minute-the movement of glaciers and the changes of sand dunes. In terms of these details, BBC’s “Earth Series” is indeed a documentary about the earth itself. It presents a seamless “Gaia”-flora, fauna, fungi, soil, rock, and atmosphere. Start the whole body.

All this integration of technology and subject matter is not enough to make BBC's "Earth Series" a milestone in the history of nature documentaries. What really makes it a god is the concept that runs through the entire series: making the earth an alien. Look like. Do you think Ridley Scott’s alien classics portray unheard of fear on this planet? No, in the close-up shot, the "alien" in the rainforest of South America is erupting from the head of a bullet ant. Do you think that only Spielberg can create a world ruled by reptiles for us? No, just give a low camera shot of ten Komodo dragons tearing buffaloes. Do you think there are magical fluorescent fungi only on Cameron’s Pandora? No, no, magic happens every night in the rainforest of equatorial Africa. The scenes of suspected CG animation remind us that human beings are still just students of nature in terms of creativity in the aesthetic sense.

How can I shoot a stunning Africa? This is a problem that the BBC has created for itself. Not to mention the large and small African feature films, the 2001 BBC series "Wild Africa" is already an all-round investigation of the African continent. In fact, Attenborough always avoided Africa when he debuted, because his colleagues Almond and Michaela Dennis had chosen Africa as the filming location. Even so, "Africa" is still full of surprises, and once again perfectly embodies the purpose of the "Earth Series" with the earth as the theme. A set of simple shots serves as evidence: In "Kalahari", the shot was first directed to a leopard walking alone, and then moved into the air. The yellow and black swaying grass in the shot seemed to be covered in a leopard's mottled coat. Animals and their habitats are integrated ecologically and aesthetically in this "anti-protective color" illusion.

Since the birth of BBC's "Earth Series", many people praised him for his objective and calm shooting angle and narration attitude. In fact, complete objectivity and calmness are impossible and undesirable in nature documentaries. The BBC’s strategy is not so much to remain neutral as to target the emotions and moods in the audience that have not been mobilized. The traditional pros and cons in nature documentaries are reversed. When the audience sympathizes with their prey, they can see the difficulty and fragility of predators, and guide people to pay attention to the warm side of "cold-blooded animals", and bring the wit, absurdity, and quirkiness of human life. Various subtle elements such as awkwardness and embarrassment are integrated into the natural world. These are the inheritance of "Africa" from the BBC nature documentary tradition. It makes all species the protagonist of the film, including the Sisyphus-style dung beetle in the Sahara Desert. The special charm of Attenborough and his documentaries is that they provide the audience with a beautiful and interesting perspective. Maybe after watching "Blue Planet", "Planet Earth", "Frozen Planet" and "Africa", we will fall in love with this planet in such a new way that we believe that even if one day we are exhausted All the mysteries of the outer starry sky, this planet is still the place where we are most dissatisfied.

View more about Africa reviews