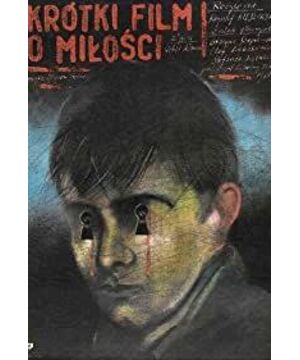

Following "The Commandments", Kieslowski filmed the second film in his series, "The Ten Commandments (Part 6): A Short Film About Love", referred to as "The Commandments". The film is not as sensational as the former, or brings shocking experiences that people can hardly bear; but it is more exquisite, more forgiving of the pain, expectation and despair of ordinary people. As the title suggests: this is a film about love, or a story of love and lovers existing in imagination and expectation.

There is a young peeper in "The Commandment", a sincere, desperate love that has nowhere to cling. In fact, "Love Commandments" is the one that is most dissociated from the prohibitions of "Ten Commandments". If the film has an accurate visual narrative opportunity, then this is a story of peeping and peeping. But for Kieslowski, the story of the voyeur is not a voyeuristic story in any sense. If the film’s protagonist Tomek was driven by the desire for voyeurism, then at the beginning of the film, a completely different behavioral motive has replaced the former. Tomek, a 19-year-old orphan, peeped at Magda obviously from a normal rather than a perverted desire, and this is undoubtedly an unusual passion. The film is presented twice: When the "repertoire" in Magda's room becomes pornographic, Tomek immediately pushes away the camera or looks away. If Tomek's peeping is still a pathological behavior, then this pathological behavior comes from the modern society shown in the film, from the alienation and indifference between people in this society. Tomek's peep of Magda is just a ridiculous and sad substitute: he tries to establish an imaginary communication, an illusion of intimacy. Because as a typical modern person, Tomek and the characters in "The Commandment" are individuals who have lost their normal communication skills and possibilities. "When contact is impossible, the desire to peek prevails." He fell in love with her, and he paid attention to everything about her; therefore, Tomek's secret life-the peeping of Magda became him The most real, most passionate and dynamic part of daily life. Eight-thirty every night is the moment when Tomek's real life begins. In a distance shortened by a high-powered telescope, in an imaginary shared space with Magda, Tomek alone experienced the joy of "sharing" an ordinary life with Magda. If there is a certain theme or similar theme in "The Commandment", then the theme is loneliness, the desire to end loneliness and establish normal communication. But the desire to end loneliness often becomes a testament to absolute loneliness. Because in "The Commandments", the lover and the beloved are so unfamiliar and separated from each other, they can be "hoped out" and cannot be seen; the inhabitants of the same neighborhood are like the inhabitants of different planets. In fact, what "The Commandment" presents is a society made up of abnormal and lonely people: whether it is Tomek, Magda, or Mahesin’s mother. What they embrace is an unknown and desperate love, and what they "have" is an imaginary or alternative loved one. In this "world", love is a luxury that cannot be consumed. Therefore, Magda chose the most effective way: simply denying love and love. Existence-"There is no such thing." Tomek's story is a story of a peeper, but also a struggler desperately trying to replace this pathological and imaginary "communication" with a real contact. He forged the withdrawal notice, he was incompetent as a milkman, just to see Magda with his own eyes; he called and called a repairman, only to intervene and interfere with Magda in a naive way Life; he left an empty bottle and gave her a clock key, desperately trying to make Magda aware of his existence. But all this was in vain. Apart from making Magda feel a little annoyance, they did not make Magda stop her hasty steps and notice Tomek, the little clerk behind the post office counter. , The milkman who woke her up early in the morning. That is just an environmental factor in modern city life. To Tomek, what is even more sad and desperate is that when Magda was crying alone in the looking glass, Tomek was heartbroken for this "silent picture", but he was completely helpless. As a desperate struggle, Tomek acted, and he tried to enter the reality. He exposed himself to Magda—a disgraceful peeper, a dark aggressor, and an unhealthy child at the same time. When Magda finally experienced the sincerity of love from Tomek, there was a profound reversal and exchange of roles between Magda and Tomek: this is the exchange and point of view of peeping and counter-peeping. The reversal of possession is also the reversal of the roles between the lover and the loved one. This time, it is Magda who is burdened with Tomek's pain: a desperate waiting and watching, a sadness of love that is unknown to the loved one. It is also a wound that is constantly being cut through by others, a loneliness that keeps asking you to face it. When he cried bitterly, Tomek was heartbroken for this "silent picture", but he was completely helpless. As a desperate struggle, Tomek acted, and he tried to enter the reality. He exposed himself to Magda—a disgraceful peeper, a dark aggressor, and an unhealthy child at the same time. When Magda finally experienced the sincerity of love from Tomek, there was a profound reversal and exchange of roles between Magda and Tomek: this is the exchange and point of view of peeping and counter-peeping. The reversal of possession is also the reversal of the roles between the lover and the loved one. This time, it is Magda who is burdened with Tomek's pain: a desperate waiting and watching, a sadness of love that is unknown to the loved one. It is also a wound that is constantly being cut through by others, a loneliness that keeps asking you to face it. When he cried bitterly, Tomek was heartbroken for this "silent picture", but he was completely helpless. As a desperate struggle, Tomek acted, and he tried to enter the reality. He exposed himself to Magda—a disgraceful peeper, a dark aggressor, and an unhealthy child at the same time. When Magda finally experienced the sincerity of love from Tomek, there was a profound reversal and exchange of roles between Magda and Tomek: this is the exchange and point of view of peeping and counter-peeping. The reversal of possession is also the reversal of the roles between the lover and the loved one. This time, it is Magda who is burdened with Tomek's pain: a desperate waiting and watching, a sadness of love that is unknown to the loved one. It is also a wound that is constantly being cut through by others, a loneliness that keeps asking you to face it.

In "The Commandment", the narrative mode of peeping and counter-peeping is also presented as a contrast and transformation between light and darkness, cold and warm. Magda's window is not only the light of Tomek, but also a space filled with warm colors-red tones. For Tomek, that refers to a warm home. Composing this red tone are the eye-catching scarlet bedspread in Magda’s room, the scarlet table sheets, the unfinished red-tone painting on the easel and the red telephone on the window. Not accidentally, the cover cloth Tomek used to cover his telescope had the same color and texture as Magda's bed cover. As the colors of two specific props, they simultaneously become a kind of exposure and concealment. What it directly exposes is desire, but at the same time it becomes a deep cover: what it covers is the omnipresent and profound loneliness that the protagonist does not want or dare to face. It uses a warm and saturated color to conceal the indifferent and bleak reality of existence. It is also a bold protest and rebellion.

"Love Commandment" has a sad and warm ending, that is the establishment of contact and communication, that is the coming of salvation, that is the ending of a classic love story. But that was just an illusion in Magda's imagination. It is actually the ending requested by the famous Polish actress Shabolovska, who played Magda. She said: "We can't give the audience a tragic ending, because people prefer fairy tales." She asked for another fictional ending, which is the ending of the movie version. It was an imaginary warm moment. That is just the desire and yearning for salvation, not the arrival of salvation. However, a reality with dreams and expectations is, after all, better than dreamless sinking and death-like life.

In a sense, "The Commandment" is a perfect film. It is a dim and slightly warm spot in Kijeslovsky's Ten Commandments. Painful, but charming; desperate, but with resistance to this despair. While expressing the desire for salvation, Kieslowski used his masterpiece to save Polish films in crisis.

View more about A Short Film About Love reviews