In traditional film language, close-up shots, as one of the ways of narration, are often used to highlight an important point: to show the characters' reactions and to emphasize an emotion. They blend into the rhythm of a cut shot. But in these trilogy, and in many other movies, Bergman tried his best to avoid the use of close-up shots, and his characters appeared alone or in pairs in the shots. They don't look at anything in particular—or, so to speak, they look at themselves inwardly. Bergman insists on focusing the lens on one of his actors. For example, in "Still in the Mirror", Harriet Anderson's face always remains in the foreground, while another character is placed in the background for a long time. Make sure that the effect when Anderson focuses on a certain place in the void can be properly expressed, and that she never blinks or does extra eye movements. Such shots undoubtedly conveyed her obsession with the voice of faith.

Bergman often uses what I call the "Bergerman's two-person close-up" shooting method-a term created to describe his simplified approach to expressing strong emotions. He juxtaposes the two faces very closely on the screen, but the characters never look at each other. Everyone is focused on an unknown place off the screen, and everyone is looking in a different direction. They are so close, yet so isolated. This is also the visual expression of his most fundamental belief in film art: we try to contact each other, but are often hindered by our inner desires.

In order to produce these lenses, Bergman and his queen photographer Sven Nikovest (now considered one of the greatest photographic artists) carried out a seamless collaboration. Nikovest made us realize that most movies simply illuminate those faces, but he uses light to guide us into them. Especially with the advent of the television era, movies use a lighting method that flattens the image style. One of the reasons we like film noir is that it uses bolder shooting angles, shadows and lighting. In a Bergman movie, if you pause on one of the two-person close-up shots, you will find that Nikovest gives each face an independent light source; he uses these lights to create a large shadow, just like A beam of dark rays is drawn between these faces, thereby separating the characters.

You can find that this practice runs through the entire "Still in the Mirror". The film tells the story of a father, his pair of children and daughter husband spending summer on an isolated Swedish island far from the world. They live in a run-down hut. inside. The opening scene of the film is unremarkable: as four people emerge from the sea bathing, they are discussing who will prepare the dinner and who will cast the net. Then a heavier topic gradually emerged. We heard the "sickness" of our daughter Karen (Harriet Anderson). The name of the illness has not been mentioned, but it is obviously schizophrenia. She has received treatment and has undergone a period of recovery. Although her husband Martin (Max von Sydoff) loved her, he still felt powerless to help her. The younger brother Minas appeared sexually sprout in the stall during adolescence, and at the same time knew his sister's physical condition very well. Father David (Gunar Bjornstrand) is a well-respected writer who has just returned from his residence in Switzerland, cold and unkind.

On the first night, the children will perform a play for their father. The theme is to illustrate the uselessness of art. It can be regarded as an allusion to his father's novel. Afterwards, Minas asked Karen if she had noticed her father's expression, because the play undoubtedly made him uncomfortable. Then the characters began to disperse, the couple went back together, and the other two went back to their rooms to rest. It was a typical Swedish summer night, hot and long, and when the darkness first fell, the sun had risen again.

This eternal day has a mysterious effect, which seems to imply that everything that happens is nothing but a pipe dream. Karen got up from the bed and headed upstairs into a dilapidated room. She seemed to be in a state of hypnosis. She pressed herself against the wall and drew an outline on the wallpaper. When she was discovered, her first reaction seemed to be disturbed, but she immediately cheered up and returned to normal. At the back of the film, she told her brother that there was a voice calling her, and opened a door on the wall. There was a group of people waiting for something on the wall. She thought it might be God. Later, one of the most famous scenes in film history appeared: She said that she saw God, and it was a spider.

After being left alone in her father’s room, she read his diary, in which he confessed that he had a strong curiosity about his daughter’s illness. He mentioned that the illness was incurable and admitted that he was eager to observe his daughter. Condition, in order to obtain writing materials. This irritated her deeply, but earlier she was laughing at her brother for peeking at pornographic magazines, and Minas accused her of being too revealing. Now her brother was searching for her on the beach and found her huddled in the wreck of a burnt-out dilapidated ship. There is an unusual scene here. The director makes full use of the lighting to carefully design a two-person close-up shot, highlighting an intimate and distant relationship between the characters. At the end of the scene, there is obviously a group of scenes suggesting incest between siblings and brothers, although Bergman cautiously avoids them.

There are other unpleasant scenes in the film, such as Karen and Martin, who have just separated, and the conversation between Martin and David. In the end, these were all attributed to the recurrence of Karen's old illness. They had to call for help. It was a helicopter, but Karen was treated as a spider descending from the sky.

You can pause on any screen of this movie to see these extraordinary screens. Nothing is random. The vertical composition divides the character in the picture into several parts, and the diagonal line composition expresses the disharmony of the character. These characters walked in and out of the pictures around the cabin, as if they were in a drama. The director used unique visual effects to highlight Karen's disordered psychosis and the psychological conflicts of other characters.

I have been deeply impressed by the wonderful production details of this film. Nikovest’s photography is essentially a re-creation of characters, his way of looking at characters, his use of compositional shadows and his clever setting of emotions. Both determine how we feel about characters. If the same movie is shot by another photographer, it may appear shallow or even stupid. Of course, Bergman will naturally share his thoughts. But the film made in this way still surprised us at the powerful appeal it showed.

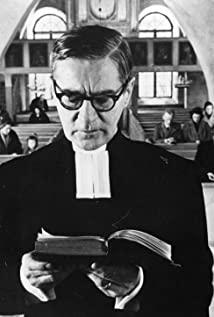

Peter Cowie (film historian, Bergman film research authority) mentioned in a short film on the CC standard DVD that the silent trilogy is Bergman’s effort to unload his religious beliefs, because he His father is a harsh Lutheran pastor, and his father's attitude has profoundly affected his life. Many of these religious beliefs still exist in his other films, and they will always be about death, guilt, sin, God, and the devil. But in these three movies, it focuses on intense pain.

"Still in the Mirror" is the first part of the silent trilogy, followed by "Winter Light" (telling a pastor trapped in God’s silent despair), and finally "Silence" (telling two The sister and her son are stuck in a strange city, entangled in the hatred of the past. The movie is silent for most of the time, or at least lacks dialogue. When the boy wandered in the hotel corridor, he was dreaming I can replace the conflict that broke out between the two sisters). In all these movies, we are completely moved by Bergman's deep concern, that is, human beings are observing the world through a dark mirror, but cannot perceive the meaning.

"Winter Light" is also among the great movies.

original:

The great subject of the cinema, Ingmar Bergman believed, is the human face. He'd been watching Antonioni on television, he told me during an interview, and realized it wasn't what Antonioni said that absorbed him, but the man's face. Bergman was not thinking about anything as simple as a closeup, I believe. He was thinking about the study of the face, the intense gaze, the face as window to the soul. Faces are central to all of his films, but they are absolutely essential to the power of what has come to be called his Silence of God Trilogy: "Through a Glass Darkly" (1961), "Winter Light" (1962) and "The Silence" (1963).

In the conventional language of cinema, a closeup is part of the grammar, used to make a point, show a reaction, emphasize an emotion. They fit into the rhythm of the cutting of a scene. But in these three films, and many others , Bergman was not using his close shots that way. His characters are often alone, or in twos. They are not looking at anything in particular - or, perhaps, they're looking inside themselves. He requires great concentration on the part of his actors, as in "Through a Glass Darkly," where Harriet Andersson's face is held in the foreground and another character in the background for a long span of time in which she focuses on a point in space somewhere to screen right, and never blinks , nor does an eyeball so much as move. The shot communicates the power of her obsession,with her belief that voices are calling to her.

Frequently Bergman uses what I think of as "the basic Bergman two-shot," which is a reductive term for a strategy of great power. He places two faces on the screen, in very close physical juxtaposition, but the characters are not looking at each other. Each is focused on some unspecified point off-screen, each is looking in a different direction. They are so close, and yet so separated. It is the visual equivalent of the fundamental belief of his cinema: That we try to reach out to one another, but more often than not are held back by compulsions within ourselves.

In framing these shots, Bergman works hand-in-hand with his cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, one of the greatest artists of his craft. Nykvist makes us realize that most movies simply illuminate faces, while he lights them. Especially since the advent of television , movies have used a lighting style that flattens the image and makes it all seem on one plane. One reason we like film noir is that it uses angles, shadows and strategic lighting more boldly. In a Bergman film, if you freeze a frame on one of his two-shots, you'll see that Nykvist has lighted each face separately, and often not from the same source; he uses the lights to create a band of shadow that is like a dark line drawn between the faces, separating them .

You can see this happening all during "Through a Glass Darkly," which tells the story of a father, his daughter and son, and the daughter's husband, isolated on a remote Swedish island for a summer vacation. They're living in a run -down cottage. The opening scenes are deliberately banal, as they emerge from a dip in the sea and debate about who will fix dinner and who will put out the nets. But deeper currents emerge. We hear about the "sickness" of the daughter , Karin (Harriet Andersson). It is never named, but is clearly schizophrenia. She has been treated and is going through a period of recovery. Her husband, Martin (Max von Sydow), loves her but feels powerless to help her. Her brother, nicknamed Minus (Lars Passgard), is balanced at the entry to adolescent sexuality,and is very aware of the physical reality of his sister. The father, David (Gunnar Bjornstrand), is an author, highly regarded, who has just returned from a stay in Switzerland. He is cool and distant.

During the course of the first evening, the children will put on a play for their father, which has as its subject the impotence of art. It can be seen as a veiled attack on his novels. Later, Minus asks Karin if she noticed how offended their father was. Not particularly. The characters separate, the married couple together, the other two in their rooms. It is a long Swedish summer night; when darkness falls, the sun is already rising again.

This perpetual daylight has an eerie effect. Everything that happens is like a waking dream. Karin rises up from her bed and climbs the stairs to a shabby upper floor, and enters a room. She seems almost in a trance. She clings to the wall and traces out figures in the wallpaper. When she is found, she at first seems disturbed, but then cheers up and acts normally. Later she will tell her brother that voices called to her, that the wallpaper opened a door, that those on the other side were waiting for something, and that she thinks it might have been God. Still later, famously, she says she saw God, and he was a spider.

Left alone in her father's room, she reads his journal, where he confesses his obsession with his daughter's illness, notes that it is "incurable," and confesses he is interested in how he could use it in his work. This deeply upsets her. Earlier she had teased her brother after catching him looking at a pinup magazine. He had accused her of wearing seductive clothes. Now her brother goes seeking her on the beach and finds her huddled inside the wreck of a burned-out boat. There is an extraordinary scene, making great use of meticulously lighted two-shots, emphasizing their closeness and their separation. At the end of the scene, there is an implication that an act of incest occurs, although Bergman is deliberately obscure.

There have been other fraught scenes - between Karin and Martin, for example, who she has drawn apart from physically. And between Martin and David. Finally all comes down to Karin having a relapse. An ambulance is called; it is a helicopter, which apparently she experiences as a spider descending from the sky.

You can freeze almost any frame of this film and be looking at a striking still photograph. Nothing is done casually. Verticals are employed to partition characters into a limited part of the screen. Diagonals indicate discord. The characters move into and out of view around the cottage as if in a play. The visual orchestration underlines the disturbance of Karin's mental illness, and the no smaller turmoil within the minds of the others.

I was impressed time and again by how painstakingly the film had been made. Nykvist's lighting is essentially another character. How he sees, how he shades, how he conceals, all sum up into how we are to feel about the characters. The same film photographed by another cinematographer might seem shallow, even silly. Certainly Bergman attracted his share of parody. But this film, shot this way, surprises us by how much power it builds.

Peter Cowie, an expert on Bergman, appears in a short subject on the Criterion DVD and says the trilogy was Bergman's way of unloading the "baggage" of his religious upbringing; his father was a strict Lutheran minister. Bergman still has a great deal of that upbringing left over for his other films, which often deal with mortality, guilt, sin, God and demons. But in these three, there is a focus almost painfully intense.

"Through a Glass Darkly" would be followed by "Winter Light," about a minister who despairs of God's silence, and by "The Silence," about two sisters and the child of one, stranded in a strange town and haunted by old hatreds and wounds. Long stretches of that film are silent, or at least lacking in dialogue, as the boy prowls a hotel's corridors, making fantasies of his own to displace the disturbance being trapped between the two sisters. In all of these films, we' re struck by Bergman's deep concern that humans see the world as through a glass, darkly, and are unable to perceive its meaning.

"Winter Light" is also in the Great Movies Collection.

View more about Through a Glass Darkly reviews