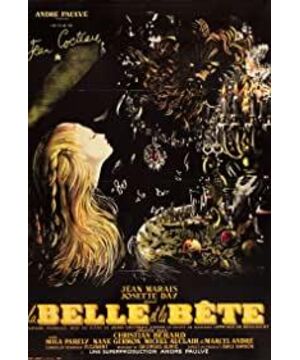

At Cocteau's behest of retaining our childlike sympathy in the preamble, one should enter his surreal realm of this timeless fairy tale with a tabula rasa (purging the classic Disney animation and Bill Condon's 2017 extravaganza out of our system for a while), and for today's new audience, a critical prerequisite of suspending one's disbelief is to lower the expectation of the Beast's appearance, who is played by a dreamboat Jean Marais under the camouflage of primitive make-up and clunky costumes.

To one's sheer amazement, what Cocteau and his uncredited co-director René Clément rip-snortingly constructs is an otherworldly, bizarre setting in and around the Beast's abode, ripe with magic touches like living statues, disembodied hands and invisible forces, which becomes all the more chilling on the strength of its black-and-white quaintness and orotund audio accompaniment, an exalted achievement which one must see with one's own eyes to induce that astounding impression.

But contrary to the forbidding surroundings and applied with a faintly subversive flourish, the Beast is emphatically portrayed as a sad-eyed, lovelorn gentleman, without brimming with the assumed masculinity and bestiality (smoke is archly deployed here), and totally throws himself on the mercy of Belle (Day), he accords plenary trust in Belle by granting her a week's away to visit her bedridden father (André), and bestowing her the key to his fortune in case she chooses to defer her return which will result in him dying with a broken heart, offering his sickly capitulation to a beauteous youth which rousingly empowers Belle's discretion.

However, it is human-looking monsters that should be answerable to Belle's delay, namely her two the-green-eyed-monster-spurred sisters Félicie (Parély) and Adélaïde (Germon), her inept brother Ludovic (Auclair) and his friend, a wooer of Belle, Avenant (Marais, again), all schemes to do away with the Beast and take their shares in his treasure trove. As expected, human avarice is punished, none other than by the arrow of Roman goddess Diana, then an inexplicable transmogrification comes about which returns a moribund Beast to his human form, aka, the Prince, when Belle falls completely under his spell of inner kindness and devotion which eventually lessens and surmounts his physical unsavoriness, a dream-comes-true of every plain- looking man and ironically, if one changes both Belle and Beast's sexes, would the yarn's appeal remain as the same? Highly unlikely.

Granted, Cocteau sprays his own magic potion onto the story's child-friendly prospect, and its ending comes off as both expected and unexpected, what if Belle prefers the rough-diamond Beast to the four-square Prince? A mischievous Cocteau knows the best.

PS for music aficionados, there is an opera version composed by Philip Glass in 1994 available which dubs all the dialogue with a more ear-soothing tenor.

referential films: Bill Condon's BEAUTY AND THE BEAST (2017, 7.1/10), Jean-Pierre Melville's LES ENFANTS TERRIBLES (1950, 6.6/10); René Clément's FORBIDDEN GAMES (1952, 8.7/10).

View more about Beauty and the Beast reviews