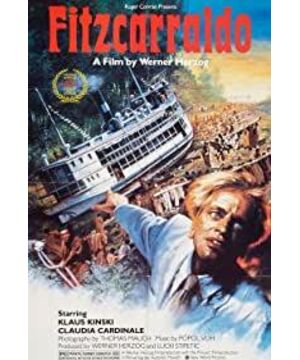

German filmmaker Werner Herzog's feature film Fitzcarraldo (1982) begins with the title character (Klaus Kinski), an ecstatic opera lover, who attempts to build a great opera house in Iquitos of the Peruvian Amazon where his idol, Enrico Caruso, can perform. The film ends with Fitzcarraldo achieving a victory of sorts that he brings a small-time European opera troupe to a boat for a single performance. However, the central dramatic action of this film is not the process of building a grand opera house but the protagonist's attempt and success in dragging an enormous steamship over a nearly vertical mountain that separates two rivers.

Herzog has a distinguishing conception of human and nature. Like its antecedent Aguirre, Wrath of God (1972), Fitzcarraldo also sets the story in the Amazonian jungle, “an unfinished land with curse that God creates it in anger”. In Burden of dreams (1982), a documentary on the production of Fitzcarraldo, Herzog describes the jungle as “the enormous articulation of vileness, baseness and obscenity”, compare to which human is only “badly pronounced and half-finished sentences”. Apart from this, Herzog's other documentary Grizzly Man (2005) centres on a tragic hero's life, examining the cruelty of wild animals and the “overwhelming indifference” of nature. It is safe to say that “human struggles against nature” is a recurring theme in his works.

However, what Herzog attempts to explore in Fitzcarraldo is not “human and nature” but rather “opera and nature”, in other word, art and nature. Although Herzog repeatedly asserted the visual primacy of his films (Rogers, 2004, p77), the musical component of Fitzcarraldo should not be disregarded. On the one hand, this Amazonian adventure film has an operatic, grand-scale narrative structure. On the other hand, while the actual'opera house' remains absent during the epic jungle-exploring journey , opera arias in various forms do appear several times in the entire film, including the opening sequence that Caruso performs arias on a grand opera house, the struggle-against-the-rapids scene that opera music is played through a gramophone among hundreds of headhunters ,and the ending scene in which a travelling opera troupe preforms Bellini's I Puritani on a steamship along the river. Especially, in the climactic scene when the boat is slowly rising up the mountain, the operatic accompaniment makes this ship-hailing undertaking a visual-musical spectacular. That is to say, though the protagonist fulfills his operatic dream indirectly, the the thematic connection between art and nature is clear in Fitzcarraldo.

Herzog is a distinguished filmmaker not only famous for his precise articulation of filmic themes but also his stylistic idiosyncrasy and monomaniacal obsession, or in other words, he is notoriously difficult to cooperate with (Arthur, 2005), which is similar to his protagonist Fitzcarraldo. Just as the eponymous character in Fitzcarraldo, Herzog pursues his dreams with ultimate madness and crazed energy, which raises the following questions: what is the relation between Fitzcarraldo and Herzog? How has Herzog's conception of “art and nature” influenced his filmic articulation to his works?

Ultimately this essay focuses specifically on the image of Fitzcarraldo and his relation to Herzog, also on the the thematic connection of art and nature in Fitzcarraldo. In section one, I conduct a detailed analysis of the party scene and I first examine the image of the protagonist as “the conquistador of the useless” and then I explore the two images of the protagonist Fitzcarraldo as well as the director Herzog. The latter half of this essay analyses the climactic ship-hauling scene in detail. By examining the complementary treatment of visual and musical aspects, it may be possible to understand Herzog's attempt to use art as a “human articulation” against the nature.

Section one: the party scene

“The conquistador of the useless”

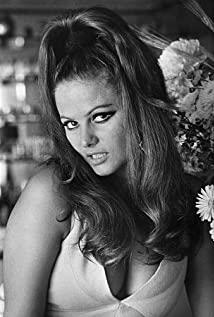

Fitzcarraldo's obsession of opera is introduced in the opening sequences that he has rowed 1200 miles for two days and nights down the Amazon to see Caruso's performance in person. When watching the opera, Fitzcarraldo believes that the dying protagonist on stage is pointing at him. He interprets it as a sacred transferring ceremony that the most renowned opera performer has transferred the musical life to him, he thus has found and absorbed the cultural power embodied in the opera (Rogers, 2004, p92). After this sacred transferring ceremony, he determines to build a grand opera house into the jungle. His lover Molly (Claudia Cardinale) considers him as “a dreamer who moves mountains”, while he identifies himself as a fulfiller of dreams.

At other point, however, a dreamer as Fitzcarraldo is someone who lacks the ability to differentiate reality from dreams. In this very opening sequence, he believes himself has absorbed the musical power of opera and since then he has transferred the real world to a musical make-believe one. To defend his dream against the artless, unmusical'old' world, he fights with crazed energy, including climbs to the top of a Church tower, striking the bell and threatening the Church will remain closed until Iquitos builds an opera house. These establishing scenes demonstrate his refusal to differentiate between the reality and dream. His monomania of the opera dream continues in the party scene when he attends with his lover Molly at a wealthy rubber baron's house.

This party scene is striking example that Fitzcarraldo lacks the ability to differentiate reality from dreams and thus feels the sense of otherness and alienation in real world. When attends the party, Fitzcarraldo directly brings out his gramophone and begins to set up this musical equipment in the middle of the hall. Meanwhile, Molly walks around waving her feather hand fan, “please, may we have your attention”, but no one seems to be intrigued. Without any introduction, Fitzcarraldo plays the opera music. In the middle of all the indifferent guests, he utterly immerses himself into his beloved opera, while Molly is looking around and trying to attract the guests' attention. Don Aquilino (José Lewgoy), a rubber baron, the host of the party, keeps talking with another magnate, remains aloof from Fitzcarraldo's action.Accompanying these is an uncut shot, just as the operatic music sounds absurdly out of place, Fitzcarraldo looks absolutely alienated. Herzog puts Fitzcarraldo in such situation to depict the sense of otherness and alienation that Fitzcarraldo always feels, recalls the previous sequences that he is either surrounded by a group of drunken card-playing barons or a crowd of shirtless foreign-language-speaking Amazonians. While Fitzcarraldo becomes completely engrossed in Caruso's mechanically reproduced voice that he remains unaware of the other audiences' inattention, a guest directly walks toward the gramophone and turns the music off. Fitzcarraldo becomes frenzied and attempts to punch the man, at the same time, Aquilino finally aware of Fitzcarraldo's existence and immediately commands the servants to take him out.Fitzcarraldo gets rid of the servants to grab his gramophone, holding it in arms, looking around the indifferent crowd, causing a minor disturbance. To clam the guests, the amused host shouts “ladies and gentlemen, don't worries, this gentleman is harmless ”, while another steward proposes a meal prepared by “the dog's cook” to Fitzcarraldo, derides him as “superb”. Accompanying this is a medium close-up shot of the stony, unsympathetic face of the steward and then the medium shot of Fitzcarraldo in an awkward position, with the heavy gramophone in arms, surrounded by the indifferent guests. Humiliated by the guests and the hosts, Fitzcarraldo continuously downs four drinks to his admired opera artists, but the steward stops him by proposing a toast sarcastically, “to Fitzcarraldo, the conquistador of the useless".As the rubber barons unable to be touched by the opera, Fitzcarraldo cries to the amused audience, “the reality of your world is nothing more than a rotten caricature of great opera”, which demonstrating again Fitzcarraldo's inability or rather unwillingness of differentiating reality from dreams .

In the eyes of the economic upper crust of Iquitos, Fitzcarraldo is nothing more than a harmless, useless and crazed “strange bird”, his eccentric attempt to bring an opera house to the jungle is nothing more than an unachievable business plan. Fitzcarraldo is juxtaposed with these European financial elites in several scenes, including the above-mentioned party scene, as well as the card-playing scene he tries to enlist the rubber barons' financial support, while Aquilino taunts and ridicules his obsession with opera. Within the frame of repetitive close-ups, Fitzcarraldo's face is sweaty, frenzied, contorted in disgust. It is worth noting that the bug-eyed maniac Klaus Kinski's rendering of Fitzcarraldo is admittedly powerful, with true madness and absolute energy, as if “a beast has been domesticated and pressed into shape" (Herzog,My Best Fiend – Klaus Kinski, [1999]).

Pure dreamers

Some film scholars see Fitzcarraldo as a colonial hero (Prager, 2012, p25) or “an imperial agent of expansion”(Davidson, 1994, p69). Opera is a symbol of the European civilization, and Fitzcarraldo's attempt to bring the opera house to the barbaric Latin America is viewed as an attempt of cultural enlightenment. In the scene when Fitzcarraldo first confronts the Jivaro, or what he calls, the “bare-asses”, he fires back with the arias of Caruso, the sound of the “White God”. He believes (perhaps at an unconscious level) opera has a particular power against the barbaric headhunters, as Dolkart (1985, p126) discusses, “devotion to and knowledge of opera represented entrance into the elite and disdain for indigenous culture ".

Despite these cultural interpretations of the figure of Fitzcarraldo, I want to discern his image in a more abstract, metaphysical meaning that, Fitzcarraldo is a pure dreamer, who seeks to fulfill his dream and eagers to express himself in an “other” land. In his words, opera “gives expressions to our greatest feelings”. Apart from the party scene, the film also shows his obsession with opera and inability to differentiate between reality and dream in other scenes, for example, when enters to the jungle, Fitzcarraldo is deeply intrigued by the words of an old missionary that “our everyday life is only an illusion, behind which lies the reality of dreams”. Fitzcarraldo replies, “actually I'm very interested in these ideas. I specialize opera myself”, making a connection between illusion and operatic articulation. As Herzog (2010) says,“What's beautiful about opera is that reality doesn't play any role in it at all”. For Fitzcarraldo, the operatic dream is the reason to live, to go through the illusions of life. As an opera impresario once said, “It [ opera] lifts one so out of the sordid affairs of life and makes material things seem so petty, so inconsequential, it places one for the time being, at least, in a higher and better world" (quoted from Dolkart, 1985, p131) . It is not the visionary of bringing European culture into Iquitos so much as the desire of articulation of “the Self” that distinguish Fitzcarraldo from those philistines, who only care about wealth and “a great name in Europe”.to go through the illusions of life. As an opera impresario once said, “It [opera] lifts one so out of the sordid affairs of life and makes material things seem so petty, so inconsequential, it places one for the time being, at least, in a higher and better world" (quoted from Dolkart, 1985, p131). It is not the visionary of bringing European culture into Iquitos so much as the desire of articulation of “the Self” that distinguish Fitzcarraldo from those philistines, who only care about wealth and “a great name in Europe”.to go through the illusions of life. As an opera impresario once said, “It [opera] lifts one so out of the sordid affairs of life and makes material things seem so petty, so inconsequential, it places one for the time being, at least, in a higher and better world" (quoted from Dolkart, 1985, p131). It is not the visionary of bringing European culture into Iquitos so much as the desire of articulation of “the Self” that distinguish Fitzcarraldo from those philistines, who only care about wealth and “a great name in Europe”.It is not the visionary of bringing European culture into Iquitos so much as the desire of articulation of “the Self” that distinguish Fitzcarraldo from those philistines, who only care about wealth and “a great name in Europe”.It is not the visionary of bringing European culture into Iquitos so much as the desire of articulation of “the Self” that distinguish Fitzcarraldo from those philistines, who only care about wealth and “a great name in Europe”.

These sequences raise questions about the Herzog's conception of dreams and how he endeavors to achieve it. The documentary on the making of Fitzcarraldo, Burden of dreams (1982), continually reasserts the impossibility of the production of Fitzcarraldo: the harsh rainforest climate, the tribal wars, crew revolts and cast changing. encounters enormous difficulties, Herzog sticks at this impossible mission and pursues his goal with madness and crazed energy, “if I abandon this project, I would be a man without dreams and I don't want to live like that", to a point where the director's dreams and Fitzcarraldo's dreams meet. In other words, Fitzcarraldo is such a powerful and complex statement of Herzog's monomaniacal obsession of “dreams”. The protagonist is a reproduction and a reflection of Herzog himself. Like Fitzcarraldo,Herzog is an aesthete with good ideas and a pure dreamer who attempts to pursue his goals. The word “pure” not only refers to the futility of the reality life and the pursuit of illusions, but also the filmic aestheticisation of uselessness. Fitzcarraldo is once mocked as “the conquistador of the useless” and likewise Herzog entitles his production diaries Conquest of the Useless (Thompson, 2011, p42), which highlights the connection between the two figures, two pure dreams. The concept of uselessness can be viewed in two ways. On the one hand, it refers to the idea of going to nowhere or returning in full circle. Fitzcarraldo's adventure leads him to nowhere: his ship is damaged by Jivaro, the same crowd who helped him move the ship over the mountain, and he fails to get rubber, coming back where he started.But the concept of uselessness is aestheticized. The final tableau is an opera performance on the boat and although the glorious dream of building an opera house in the jungle fails, this triumphant ending scene is seen as a victory of sorts, a fulfillment of dream. On the other hand, uselessness can be seen as inability of self-expression, of “human articulation”, which I explore in detail in section two.

Section two: the climactic scene

Herzog’s “Ecstatic truth”

Herzog is a well-known auteur for his stylistic idiosyncrasy, recurrent themes and cultural-historical sensitivity (Dolkart, 1985, p126). For a better understanding of Herzog's distinguishing view of natural landscape, it is essential to look at his own words: “ I wanted an ecstatic detail of that landscape where all the drama, passion and human pathos became visible” (My Best Fiend – Klaus Kinski, [1999]). For him, landscape is not a backdrop of outstanding scenic beauty in Hollywood-style commercials , but rather a place filled with “indifference of nature” (Grizzly Man, [2005]), with “almost human qualities” (My Best Fiend – Klaus Kinski) and with “overwhelming and collective” and full of “fornication and asphyxiation and choking and fighting for survival and growing and just rotting away" (Burden of dreams, [1982]).Again in Fitzcarraldo Herzog sets the story in the barbaric Amazonian jungle, “an unfinished place with curse that God creates in anger”. Herzog's view of nature sounds deeply pessimistic, but he claims he admire the nature, “I love it very much. But I love it against my better judgment" (Burden of dreams).

The most striking example to demonstrate Herzog's obsession with visual authenticity of the natural landscape in Fitzcarraldo is the climactic scene when the steamship is dragged over the mountain separating the two rivers. This climactic ship-hauling scene consists of a series of documentary-like shots and a static one-minute long shot. It begins with several shots of the mechanism within the steamship and details how the complex pulling system works. The long documentary-like sequence also details their effort: cutting a path through the dense jungle, oiling the pulleys , and setting the hauling system. In these shots, the images of the jungle have a very crude, unfinished, and primeval texture, the natural landscape is represented with the visual authenticity that Herzog aims to impart. In the scene, we then hear Fitzcarraldo's shouting,“We have two dead man”. In a tracking shot, he fretfully climbs over the supporting stakes, while Cholo, the mechanic of Fitzcarraldo's crew, excitedly explains the ship-hauling plan to him. “We have two dead man!” Fitzcarraldo ignores Cholo and repeats, recalling their last failed attempt that two Jivaroan people died when dragging the ship. Additionally, this scene also reminds us of the director's own ambiguous filmmaking anecdotes, blurring the distinction between filmic reality and reality per se.Additionally, this scene also reminds us of the director's own ambiguous filmmaking anecdotes, blurring the distinction between filmic reality and reality per se.Additionally, this scene also reminds us of the director's own ambiguous filmmaking anecdotes, blurring the distinction between filmic reality and reality per se.

To pursue the documentary-like truth or rather what he called the “ecstatic truth”, Herzog prefers shooting on location rather than filming in studio (Ascárate, 2007), no matter how dangerous the shooting sites would be or what enormous difficulties the cast and crew would face. In addition to the authentic shooting sites, Herzog also employ the local Aguaruna people to play the “uncultivated” Jivaro, and insists on using the full-sized steamship in the climax instead of dismantling before the portage and also refuses to adopt miniatures or special effect. He also refuses the Brazilian engineer's original ship-hauling mechanisms design, which the ship would be hauling at 20 degree up the mountain while Herzog insists on 40 degree. In Filmmakers' Choices, John Gibbs (2006, p14) points out the significance of filmmakers' decision-making, and

one of the best ways of determining what has been gained by the decisions taken in the construction of an artwork is to imagine the consequences of changing a single element of the design.

(John Gibbs, 2006, p14)

Perkins also contends “the director's job is, particularly, to hold each and every moment of performance within a vision of the scene as a whole” (1981, p1143). In the case of Herzog, changing 40 degree to the initial 20 degree may seem insignificant but the vision of the climactic scene (in which the ship is rising up in a quite peculiar angle) may consequently changed. By considering why Herzog refuses the initial doable design and insists on the impracticable one, it may be possible to understand what he calls “the sublimity of images and their illuminating effect” (Weigel, 2010) in his films.

Because of his insistences on visual authenticity, Herzog earned a reputation for his “neurotic obsession” of ecstatic truth, and has been criticized by press and scholars. On the one hand, some dislike the idea of “realism” (Kael, 1982). On the other hand, some question Herzog's view of nature and criticize it as nihilism (Arthur, 2005). As in Herzog's films and documentaries, the vivid images of picturesque flora and fauna contradict his concept of nature “vileness, baseness and obscenity”, "The harmony of overwhelming and collective murder". Despite the criticism, Herzog's insistences seriously affect the visual authenticity of his works. In Fitzcarraldo, Herzog captures the distinguishing unique beauty and cruelty of nature, and composes his unique images of filmic landscape in the climactic scene.

Civilization's opera and barbarism's silence

Despite his obsession with visual authenticity, Herzog does not tend to prioritises the visual over the aural. In this film, music operates on two levels; one is the diegetic music of Caruso's operatic recordings. Opera is sophisticatedly used in both time and place and functions as a crucial component in Fitzcarraldo, as William Van Wert (1986, P68) contends that, “the spectator may very well marvel at'haunting' visuals in Herzog's films, but the music that accompanies those visuals is what charges them, providing the ' haunting,' as much as the camera or editing”. In the journey, Fitzcarraldo equipped himself with a gramophone that plays arias. Opera becomes a travelling art and a mobile theatrical event, and always function as an external, often incongruous complement to the visual landscape.

The second musical level is the'acousmatic' sound (Chion, 1999): the Latin American folk music composed by Popol Vuh and the ominous chanting and primitive drumming noises of the Jivaros. In an earlier scene when the crew enters the Jivaro Indian domain, they hear the constant noises of drumming and chanting, a threatening signal from the headhunters. As the beating sounds getting louder, Fitzcarraldo brings out the gramophone, and uses opera as a weapon of sorts to confront the Jivaro's ominous chorus. The two contrasting sounds meet and mix in the midst of the primeval jungle, and then the Indian chorus is swallowed by the sound of opera arias and gradually mutes and disappears. As Dolkart (1985, p135) argues, opera is used to sharpen the contrast between civilization's arias and barbarism's silences.At that night when Cholo proposes to use violence against the Jivaro's, Fitzcarraldo replies to take advantage of the myths of their gods, “this God doesn't come with canons. He comes with the voice of Caruso”. The next morning, when finds out his crew has deserted him, Fitzcarraldo again plays the opera. In a long tracking shot, the ship equipped with opera arias is slowly sailing up the river, while the Jivaros remain silent and mute. It appears that the civilization's sounds have dominated the barbaric areas.the ship equipped with opera arias is slowly sailing up the river, while the Jivaros remain silent and mute. It appears that the civilization's sounds have dominated the barbaric areas.the ship equipped with opera arias is slowly sailing up the river, while the Jivaros remain silent and mute. It appears that the civilization's sounds have dominated the barbaric areas.

These musical and narrative strands converge at the climactic scene. With human efforts and engine power, the steamship is slowly moving over the mountain. Presented in a peculiar shot, the ship is slowly rising up in an oblique angle, while Fitzcarraldo is standing front the ship and shouting, to punctuate this dramatic moment: “we forget something –Caruso! Enrico Caruso!” After a shot of the bottom of the ship showing the mechanism and how it works, Caruso's beautiful aria resounds in the midst of the primeval jungle, initiating an epic, breathtaking visual-musical interplay. In a one-minute long static shot, the ship is slowly moving up the steep slope with Caruso's operatic accompaniment.

In the climactic scene, Caruso's voice is no longer a mere incongruous complement or a contrasting sound against the barbarism, but as an integral component of the performance. Opera is a high art that combines extensive scenery and virtuoso singing, and all integrated into one grandiose visual-musical spectacle (Dolkart, 1985, p131). Herzog reconstructs the natural landscape, transforms the jungle into a grand opera stage. While watching this scene of the enormous steamship slowly moving up in the middle of this jungle stage, we become the audience inside an opera auditorium, and this one-minute long static scene is a breathtaking visual-musical opera spectacle. Despite the terribly scratchy quality of the opera recording, Caruso's voice is with “an unspeakably dignified beauty, sad and strong and moving” (Herzog , 1982). To some extent,the steep mountain and the barbaric jungle and the steamship hauled by the “wild” Jivaro, are all working together to accomplish an opera performance. “We can feel the theatricality of the place, we see the image of the opera that surges from the sweat of the jungle” (Herzog, interview, 1982). The highly artificial, civilized high art is connected with barbaric jungle in harmony for the first time.

Herzog, with sense of irony, completes his use of opera in the rapids scene when the ship is careering down the impassable river. In Jivaro's myths, the divine white ship could drift through the rapids to soothe the “the angry spirits” so the chief of the Jivaro's severs the rope and sending the ship floating down the Pongo River, the most dangerous place in the jungle. During the scene, Herzog adopts point of view shots. As the ship crashes helplessly through the raging river, the POV shots are violently shaking. In the shot when the ship is adrift in the treacherous rapids and slams into the cliff and jars the gramophone on, once again the off-stage operatic accompaniment resounds throughout the jungle and the rapids. The opera once again turns the struggle between the steamship and the jungle into a nautical ballet sequence.When the ship eventually drifts through the river, the arias slowly dissolve, completing the final performance.

Unlike the earlier scene when Fitzcarraldo using the opera as a weapon to dispel the violence, the rapids scene is not about the confrontation between civilization and barbarism, but about interconnection between opera and nature, or rather art and nature.

“Human articulation” against the nature

In Burden of dreams, Herzog describes the jungle as “the enormous articulation of vileness, baseness and obscenity”, compare to which human is only “badly pronounced and half-finished sentences”. I borrow the term “human articulation”, and to explore the attempt of human's articulation against nature in both the ship-hauling scene and the rapids scene. In Herzog's view, poetry, painting, filmmaking are all about articulation, in which we can reach a deeper truth –"an ecstatic truth". In other words, art is, in essence, about articulating ourselves.

In the essay of musical and textual analysis in Fitzcarraldo, Rogers (2004, p97) asserts that Fitzcarraldo's opera “is able to attack the Amazon on its own terms.” Likewise, in an interview, Herzog describe the moment when Fitzcarraldo plays the opera, “The jungle seems to be paralyzed with emotion by Caruso's beautiful, sad voice” (Herzog, 1982). To be fair, one must admit that the opera, whatever the form, stage performance or the scratchy recordings, has no power against the rapids or the nature. As Kant (2010) says, “the irresistibility of the power of nature forces us to recognize our physical impotence as natural beings, but at the same time discloses our capacity to judge ourselves independent of nature as well as superior to nature ”. Art can never really “beat” or “conquer” nature,as much as human is never fully capable of expressing or articulating own self in relation to the nature. What lies in Fitzcarraldo is that self may encounters with other, but not subordinating the one to the other.

This is another aspect of “uselessness” I try to explore, which is the inability of self-expression, of “human articulation”. In several earlier scenes, Caruso's voice resounds throughout the jungle, while nature is responding to this human articulation with enormous silences and overwhelming indifference. The strangeness and foreignness of opera echoes the earlier party scene that not a single guest seems to care or shows any interest in Caruso's operatic voice, though Fitzcarraldo is desperate to attract other's attention and express himself. “Opera's use lies in its uselessness” (Koepnick, p161). Like poem, and other art, opera is highly artificial and aesthetic. Its values lie in a deeper, purer, more abstract dimension. In other words, in the final rapids scene,opera is not used as a civilization weapon or a practical tool to conquer the nature, but rather as the articulation of humans, an attempt to express the self toward the other.

In the ending scene, Fitzcarraldo brings a small-time opera troupe to a boat for a single performance. With a royal seat next to him, Fitzcarraldo is standing on the top of the ship Molly Aida, before his eyes is a sea of jubilant people –All people unite, his lover Molly, the locals and the entrepreneurs, waving and applauding. The ending is seen as a triumph. The triumph lies not in the achievement of wealth or good names, but the great efforts and desires to articulate, and the admiration of beautiful art.

Conclusion

In conclusion, by interpreting two particular scenes of Fitzcarraldo in detail, this essay examines the images of Fitzcarraldo and Herzog, and explores the interconnection of visual and musical aspects in this film. In section one, I examine the party scene in detail to explore the image of Fitzcarraldo, while he views himself as a dreamer, other may see him as “useless”. And then I explore the interconnection between Fitzcarraldo and the director Herzog. In section two, by interpreting the climactic ship-hauling scene, I look into Herzog's view of nature and how his pursuit of visual authenticity affects the representation of natural landscape in his film. I then examine the visual and musical aspects of the film, and gain a better understanding that how Herzog attempts to use art as a “human articulation ”Against the nature.

Fitzcarraldo is such a complex and powerful statement and it is worth closely reading. Herzog is a genius auteur famous for his formidable gifts of expression. He writes and speaks with poetic precision and therefore sometimes it is difficult to paraphrase his distinguishing expressions. As a result , this essay frequently quotes Herzog's words from different materials, including interviews, documentaries and articles, to directly show Herzog's views. By doing this, I do not mean to assume the director's intentions or find the “truth” of his works. The director is not the authority of films but a reader like us. As Dow (1996, p15) notes that, “the act of interpretation and argument by the researcher is paramount”.

Bibliography

Arthur, P., 2005. Burden of Dreams: In Dreams Begin Responsibilities [online]. Available from:

https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/367-burden-of-dreams-in-dreams-begin- responsibilities

Ascárate, RJ, 2007. “Have You Ever Seen a Shrunken Head?”: The Early Modern Roots of Ecstatic Truth in Werner Herzog's “Fitzcarraldo”, PMLA, 122(2), 483-501, Published by: Modern Language Association

Chion, M., 1999. The voice in cinema. tr. C. Gorbman. New York: Columbia University Press.

Davidson, JE, 1994. Contacting the Other: Traces of Migrational Colonialism and the Imperial Agent in Werner Herzog's Fitzcarraldo, Film & History: an interdisciplinary journal of film and television studies, Volume 24, Numbers 3-4, 66-83

Dolkart, RH, 1985. Civilization's Aria: Film as Lore and Opera as Metaphor in Werner Herzog's Fitzcarraldo, Journal of Latin American Lore, 11(2), 125-141, Printed in USA

Dow, BJ, 1996. Prime-time Feminism: television, media culture, and the women's movement since 1970, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Herzog, W., 2010. On the Absolute, the Sublime, and Ecstatic Truth. Tr. M. Weigel. A Journal of Humanities and the Classics , Third Series, 17(3), 1-12

Published by: Trustees of Boston University; Trustees of Boston University

Kael, P., 1982. New Yorker, 58:35 (October 18,1982), 173-178

Koepnick, L ., 2012. Archetypes of Emotion: Werner Herzog and Opera. In: A Companion to Werner Herzog, ed. Brad Prager, West Sussex: Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Prager, B., 2003. Werner Herzog's Hearts of Darkness: Fitzcarraldo, Scream of Stone and Beyond, Quarterly Review of Film and Video, 20(1), 23-35

Rogers, H., 2004. Fitzcarraldo's Search for Aguirre: Music and Text in the Amazonian Films of WernerHerzog, Journal of the Royal Musical Association, 129(1), 77-99, Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. on behalf of the Royal Musical Association

Sheean, V., 1956. Oscar Hammerstein I : The Life and Exploits of an Impresario, New York, 252-253.

Tambling, J., 1987. Opera, Ideology and Film, Manchester: Manchester University Press

Thompson, KM, 2011. Madness on a Grand Scale. In: The Cinema of Werner Herzog: Aesthetic Ecstasy and Truth, London: Wallflower Press

Wert, WV, 1986.'Last words: observations on a new language'. In: The Films of Werner Herzog: Between Mirage and History, ed. Timothy Corrigan, London, 51–71

View more about Fitzcarraldo reviews