/Wang Xiaoer

Masoch used to compare his women to marbles, beautiful and cold, in his imagination, wrapped in fur, holding a whip in his hand The goddess is both the giver of pleasure and the savior of the soul. The woman in Polanski's "Venus in Fur" subverted the texture bridge between women and marble as soon as she appeared. The woman (played by Emmanuel Senier) was full of sensuality. The breath of the world. It's just that when she merges with the "Wanda" image on the stage, it is like the director (played by Matthew Amarek) in the film, which is shocking. This is the charm of women, coming and going with a sense of play and mystery.

Masoch’s novel "Venus in Fur" is more suitable for stage performances. The fanatical and neurotic movements and language of the characters are more likely to be enlarged on the stage, and the more they are enlarged, the more they can be separated, which is convenient for the audience to take distance. Feeling to examine sadomasochism. If the form of expression on the stage is completely eliminated, a mere film may not be able to control the performance of the characters' actions and language. Polanski chose to adapt from the stage play, establish a confined stage space in the film, and establish an interactive connection between reality and fiction. The combination of stage and reality is not novel from the perspective of film history, but it is an ideal way to express "Venus in Fur". At the same time, the film’s treatment of space and characters reminds people of Polanski’s previous work "Killing". Both use narrow space to express characters, which greatly mobilizes the expressive power of characters’ language and actions. At the same time, they can also Create sufficient drama and firmly confine the audience to the established space.

The whole movie is like a dream, like Marsock's reimagined Marble Venus after the resurrection, and he will come to the theater to complete a heart-catching stage show. In the end, the mysterious Venus disappeared into the fog, leaving behind the frightened man bound on the stage. However, the "Dreamland" in the film does not have the fragrance of warmth by the stove like the novel. Polanski restricts the background to a cold rainy night, and the streets passing by the camera in the opening show a sense of mystery and depression. Such an atmosphere also sets the tone for the performance of gender power. If Masoch’s novels confess a gender relationship that transcends the secular, and use literary writing to mark the meaning of "sadomasochism," then Polanski uses this as a background to show gender in depth. Power and its conversion possibilities.

The women in the film have a condescending aura as soon as they appear. From the initial direct and even vulgar language to the role-playing on the stage, they all show the potential of "tyrants" in gender relations. The director in the film, as a male, appears impetuous and frightened, lacks firm will, and seems to be labelled as a "slave". The fictional story the two performed on stage-the play "Venus in Fur"-continued and consolidated the relationship between the tyrant and the slave. Once on the stage, the slave instantly stepped into a dream, enjoying the charm of the tyrant, and crawling to follow the thinking of the tyrant. However, rather than saying that the stage provides a magical field and giving characters new possibilities for identity, it is rather that clothing has magical powers, just like the ubiquitous fur coats in the novel. On the stage, women constantly undress and dress, while men change different costumes. At the same time, each change of costume means that the character's status can be established or reshaped. What is interesting is that the relationship between the characters in the film, including the real space and the fictional space on the stage, reverses the power relationship between the director as the theater "tyrant" and the actors as the "slave" in the usual sense. Women continue to overstep, question and modify the director's creation, while at the same time, the director is constantly compromising and accepting. This has a very interesting mapping relationship with the sexual/masochistic relationship between female tyrants and male slaves.

The sadomasochistic image that makes the mapping possible is a whip in the novel, and a script in the film. The similarity between the two is that the experience of pain and pleasure is mixed in the process. In the eyes of the drama director, the script is sacred, otherwise he would not be so surprised and disappointed when a woman took out the dirty and wrinkled complete script, if he noticed that he had a clear contempt for this woman who suddenly visited If this is the case, the feeling of loss of ignorance of male authority becomes even more prominent. At the beginning of the film, the director's right to speak was deprived of it like a game by women, and the inherent mode of gender power went inverted.

Regarding the inverted gender power relationship, the film spares no effort to confirm and consolidate the overhead and overhead shots. The actress under the overhead shot shows her strength with stunning performances and endless words, while the male director under the overhead shot is even weaker. Even if the plot develops, the male director becomes the "tyrant" on the fictional stage, and the camera shoots his image up, but the cross-dressing gives him a clown appearance, exaggeration and tweaking, which fully exposes the falseness of the moment, his Kong Wu moment Was crushed. At the same time, Polanski is also sparing no effort to construct another layer of time and space with the help of mobile phone calls, and to put pressure on men, thereby exposing his personality. The successive calls to urge the film director have become a persistent crisis for the director in the film, and have also opened the curtain of his status as a "slave" in reality. The addition of the telephone plot not only expands the space of the theater, but also adds effective means for fiddle with the relationship between the male and female protagonists.

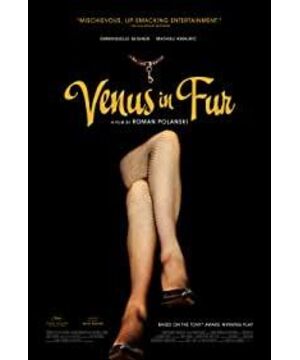

At the end of Masock's novel, "I" repeatedly asked Severin "What's the moral of the story?" For Polanski's films, the audience also had similar urgent questions. The film’s inverted performance of gender power in the traditional sense is not so much a point to gender power itself, but rather an exploration of attitudes towards values. In the theater, there is a female tyrant and a male slave. The former's understanding of the novel and the stories and characters on the stage is vulgar, but it represents the rational judgment of the so-called normal world, and a moralistic attitude towards sadomasochism; while the drama The director's interpretation of the characters and the relationship between the characters in the novel carries the artist's unique sensitivity and imaginative temperament, but his idealized creation and interpretation are accused by the "female tyrant" as hypocritical and pretentious. But in fact, the problem is not so simple, because Polanski’s position seems to be more inclined to the female tyrant in the film. Her mystery and manipulative ability are just like Polanski’s directorship. Only he can control the opening and opening of the theater’s gates. closure. If this is the case, then the sadomasochism literature of the 19th century has really become a disdainful pornographic novel, and it is no wonder that the poster will show up as a woman’s high heels breaking through the authority glasses. If the reversal of gender power is the appeal of dramatization in the film, then the value judgment is the rational thinking behind the dramatization.

The "Wanda" and "Severin" born in the 19th century have now become symbols of sadomasochism. Wanda’s tyrant behavior in the novel eventually became a rescue and a cure for fantasy love. Polanski's film is more like a questioning and warning. The novel is frank to the self, while the film is a coercive questioning, just like an actress who pursues the director in the same abnormal life as Severin in the novel. This forced questioning shows a different gender power relationship, and through this process of performance, it seeks answers and recognition of value judgments.

View more about Venus in Fur reviews