At the same time, from a certain angle, Antonioni’s shots are very focused on sex. They shoot women's bodies dazzlingly, often through voyeuristic angles. What they want to show is the heterosexual relationship in crisis, adultery, and sexual jealousy. Desire is transferred from one role to another, suppressed or destroyed. Perhaps it is precisely because of their abstraction, their "non-dramatic", their lack of narrative rhythm and clear plot setting that makes Laura. What Malvey said is the "observability" of the woman's body. But what Antonioni adopted was not the Hollywood method described by Malvey, nor was it the pioneering method advocated by the latter. Antonioni took the trouble to show the actress’s beautiful body in his movies, sticking to the wall, standing in the doorway or window frame, the shadow in the mirror or glass, the overhead shot or the back shot on the stairs, lying on the bed or recliner Above, a close-up of bare arms, shoulders, neck or throat. These shots are not part of the narrative and do not have any effect on the narrative. They are similar to photos and resemble the common expressions in business culture, such as fashion photography, posters and advertisements. In Blow Up (1966), this relationship with photographs and fashion photography has been carefully themed and discussed.

Of space and

I wanted to find a way to both Antonioni's movies - and of space, linked. What I mean by "space" has two meanings: three-dimensional, whether it is natural or artificial, and two-dimensional. In front of the moving camera, they have inextricably linked interactions, constantly changing and connecting. The sex I am talking about refers to both their content and what they cause: it is usually a woman’s body that causes lust, but the viewer’s pornographic gaze is often anxious and confused. There are also such shots about men, Marcelo. Mastroiani in "Night" (La notte, 1961), Alain. Deron in "L'eclisse" (L'eclisse), David. Hemings in "Zoom In", Mark. Frécht is in "Cape Zabriski" - but this is nothing more than replacing the anxious and perplexed with a woman. I feel that in Antonioni’s films, the woman’s body sometimes appears as the end of an abstract space. It turns “space” into “location” and at the same time recombines the lens with the story; and sometimes it divides the space, When the narrative is terminated, a typical modernist separation is formed between the body and the space.

I think this combination of space and sex should be viewed from a historical perspective and commented in detail. Antonioni's films, especially those in the early 1960s, appeared as a product of a special period of Italian society-the expression of art, culture and sex, which clearly influenced that period. Many critics look at his films with humanity and beyond history, thinking that they are about the alienation of people and the general public, rather than about the sex of people of specific classes and races in certain places, and the body of people. This ignores this important point. This kind of criticism first recognizes that those bodies related to sex have a specific and clear role in the film, and then it believes that a woman's body symbolizes a universal (no race and no time limit) situation: "The woman in Antonioni's film is Symbolic roles represent the pursuit of the director and the inspiration captured by intuition. Most of them are about the human situation.” (Micheli, 1967) “Antonioni’s women are the only way to reveal the essence of the search” (Chatman, 1985). This generalization should be consciously resisted.

Space and location

First, let me explain the meaning of space and explain their role in films, especially films before the 1960s. The lens space can be divided into two types. The first is the mathematical space, the space with specific geometric forms, including the "empty" between objects and the "full" that is not empty. Henry. Lefebvre and others believe that the concept of mathematical space emerged after the advent of Descartes' philosophy. Modern physics is inspired by it, and believes that space is not a tool for people to understand the world (like Aristotle's metaphysics), it is independent of ideology. There is also social space, which is highlighted through social and economically distinct and mutually opposed social structures—commercial downtown/suburban residential areas; high-end apartments/slums; urban/rural areas; center/peripheries. Lefebvre wrote: Every society, every mode of production and their branches (societies in the general sense) create space and belong to themselves. The ancient cities have all created suitable spaces with specific centers and polycentrics (markets, temples, squares, etc.). By referring to these, combined with the times and lifestyles they live in, one can understand the meaning of space.

Architecture occupies space and changes space, thereby providing a way to combine mathematics or physical space and social space—they are physical and the construction of social space, which outlines a form of social and economic life. When a mathematical or physical space is considered as a social space, to put it simply, when a building is inhabited or visited, according to the philosopher Edward. What Kayser said, it became a location. Kaisai’s point of view is that the space with human traces is the location-"There is an amazing fact that is often overlooked by us, when we envision a completely empty time and space (no one and no time vacuum), theoretically , As long as people and things appear, no matter how huge they are, they become places.” (Kaisai, 1993)

Whether from a natural perspective or a humanistic perspective, space and location are of great importance in Antonioni's films. But this is not to say that each of his films has a clear location, some have, some don't. There are often early documentaries. We can even say that they are movies about people and places, like the rivers and banks in "People of Po" (Gente del Po, 1943), and the streets of Rome in NU (1948). Later, especially in the early 1960s, the location became blurred, and sometimes several locations were confused. The stock exchange in "Eclipse" is in Milan, Italy's main commercial city, not Rome, but in fact the stock exchange in Milan is not important. EUR, the suburbs where most of the scenes take place in the film, is an abstracted modern space, separated from the historic city center and ancient residents that hardly appear in the film. Between 1934 and 1942, in order to welcome the 1942 World Exposition (cancelled by the war), a passage was built between the EUR and the center of Rome. By 1960, the EUR had become a bustling commercial area and a center of middle class. Similarly, Antonioni believes that "Zoom" is not a film about London. "Location is important," he told Alberto during an interview in 1968. Moravia, he was about to start filming "Zabriski Cape" at the time, "Zabriski Cape" can happen anywhere, and "Zabriski Cape" is about the United States."

Antonioni's career, especially It was in the films of the early 1960s that his handling of space was closely integrated with related characters. Space must make way for narrative. In some films, characters have achieved an overwhelming victory over space. This change is achieved through scripts and editing. The original rules are all broken, and the choice of shots in a certain location must be determined by the needs of the plot or the role. In this way, the empty shot symbolizes that someone is about to walk in, like an empty stage; when the character walks out of the screen and the shot becomes empty again, he must immediately switch to another scene. This kind of space conversion is also a time conversion. Unmanned shots have no time significance. They are an obstacle to narrative and a factor that makes the audience impatient, so empty shots need to be cut off. The logic of this kind of movie is also very simple. This seems to coincide with Kaiser's concept of time and space. The location is defined by the existence of human beings and even the existence of imagination. Without this existence, it retreats to an abstract and empty space just like a vacuum.

It is said that Antonioni’s first film to challenge this tradition was "Avenger". When the film started 20 minutes later, Anna (Lee Masari) disappeared on the island. Her friends rowed around to search for her. The search lasted 30 minutes. In the process of searching, the camera is aimed at the rocks, sea and sky, and there is no one everywhere, creating tension between nature and people. At first, the audience would hope that Anna or Anna’s corpse would appear in the lens quickly, but the lens was so patiently searched that they were confused and could only wait patiently. However, this group of lenses still used mainstream traditional methods: it distorted the rules. But it didn't break it. All the shots on the island have one or several characters entering or leaving, or the camera moves to make the characters enter, except for the two shots from the perspective of Crado (James Adams) when the storm is coming on the sea. Some camera movements bring about a lack of sense of direction. The characters inside either suddenly appear close or stand in groups on the edge of the screen. It seems that the camera is searching for Anna and Anna's traces on the island, and then constantly returning to the real searcher. In other words, the use of the lens is for the narrative search service. Also, Anna's disappearance also triggers other plots: Sicily and the other two main characters-Sandro (Gabriel Filzetti) and Claudia (Monica Witty) are entangled. The missing Anna has always been a shadow on the sexual relationship between Sandro and Claudia. She is an invisible point in a love triangle, and it is also the reason for the restlessness of the other two.

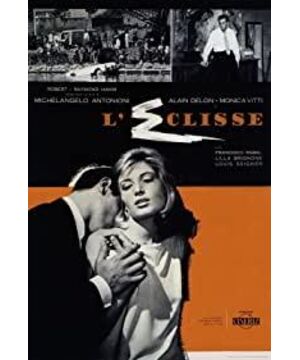

In "Night" and the more extreme "Eclipse", Antonioni used more non-mainstream spatial processing methods. The end of the latter film is a set of montage shots of the streets of Rome, ranging from 5 to 7.5 minutes, and the length of the different versions is different (after a screening in Cannes in 1962, the producers Robert and Raymond Hatch Ham shortened it because the audience reacted horribly to it), there was no dialogue in it, and none of the main characters appeared. The location is not used as a scene or foil, subject to the plot setting, but becomes the subject of the shooting. There is no dialogue, only broken sounds-sprinklers, water flowing from graduated barrels into the sewers, buses, the shouts of children, and Giovanni playing piano and wind instruments. Fragments of Fosco's atonal music. Although there are people appearing in the camera, the person driving the carriage, the nurse pushing the stroller, the person waiting for the bus, the person getting off the bus, the person on the balcony, the person turning off the sprinkler, most of the shots are empty . The main characters, Victoria (Monica Viti) and Piero (Alain Delon), did not show up, and they agreed to meet at that location that evening, the second day, and the third day. As night fell, a street light came on, the ending caption appeared, and this set of shots ended.

In "Adventure" or "Night", there is a more ambiguous relationship between this sequence of shots and the narrative. On the one hand, after a long narrative, the audience naturally expects the appearance of the two protagonists, or only one side is fine, but Every scene brings them disappointment, and the "end of the play" puts an end to the expectation. In this respect, this set of shots is characterized by the absence of the protagonist, but the protagonist still controls the narrative and the viewing of the film. On the other hand, the absence of the protagonist shifts the audience's attention from narrative to inanimate objects and locations. Streets, rain barrels, sprinklers, leaves, and buildings become characters, not just symbols of the absence of the two protagonists. In fact, if you watch the movie attentively or repeatedly, you will find that many scenes are related to the characters, such as the rain barrel. Victoria once threw a piece of paper into it and dipped his fingers in it in another scene. But other scenes appeared in the lens for the first time. All in all, this set of shots not only promotes the narrative but also dissociates from the plot.

"Il deserto rosso" (Il deserto rosso, 1964), Antonioni's first color film, is not as extreme as "Eclipse" in this respect. The former does not separate the location from the narrative, nor does it allow the environment to replace the character narrative. But this film attracts attention in another way: Compared with the films before or after Antonioni, it combines the location and the subjective world of the characters more closely. In making the external environment allude to the inner world of the characters, this film is experimental. The use of colors through various methods (color filtering, insufficient or excessive exposure, long-distance photography, shooting without focus to increase density and mixing colors, coloring a part of the environment or the building) to achieve the performance of Juliana (Muni Ka. Witty) neurotic purpose. "Red Desert" also discusses color, location, and gender: Juliana, unlike her husband, Carlo Chionetti, is far away from the noisy factories of Verona, and away from the glaring red buildings and yellow smoke. She was unhappy and unwell. She lived in a icy white and blue highly modern room with a rectangular window facing the pier. Even her son's toys: robots and microscopes belong to the industrial world created by men. She hopes to decorate the room with cool colors, such as blue and green. She felt that when her son was sick, she told him the story of a girl who lived on the island. The girl was swimming in the clear water with pink sand beaches and rocks carved into various shapes by the water. This is the only set of tones and plots in the film. Maintain a consistent lens. It opposes the feminine nature and natural scenery (the physical rock) with the masculine industry and its environment. In other films, the gendering of the environment is also expressed, the opposition between the town and the natural landscape (Rome, Noto, Taormina versus the sea and rock of Lisca Bianca) or in the "Zabriski Point" (Los Angeles vsus Death Valley) . The stock exchange in "Eclipse" is a rushed, masculine, and time-limited place. The women inside, such as Victoria's mother (Lilla Brignone), have an incomprehensible addiction to it—like she said to Piero Yes, she can't understand that her mother can live like that. She herself yearns for another rhythm of life. In fact, she lives in a place where she is not separated from others and not restricted by others.

Framed space

Expressing the three-dimensional space in a flat form (such as eliminating the depth of the picture or the distance between the picture and the audience) and confining the picture to four sides is the characteristic of movies and photography. The best discussion about film space appears in Burch's "Film Practice Theory", which was first published in 1969 under the name "Film Practice". Burch distinguishes the space of the screen (the space within the frame) and the space outside the screen, and divides the latter into six parts: outside the screen (upper, lower, left, and right), behind the screen (for example, behind the wall or building, If they appear as the background), in front of the screen (behind the camera, the space occupied by the audience). In 1976, Stephen Heath used psychoanalysis and Marxism to develop Burch's theory in "Narrative Space", emphasizing the "acceptance" and "adjustment" of the film's "classic continuity" to the space outside the screen, eliminating the artifacts of the film. Build a more stable but unreal scene location for the audience. There are also two scholars whose theories are related to Antonioni: Russian formalist Boris. Kazansky and Eugene of Soviet Notation Linguistics. Lotman.

In the 1927 article "The Essence of Movies" by "Poetika kino", Kazanski believes that among all art forms, film and architecture are the closest. “Architecture not only shapes surface and form, painting and sculpture, but also includes space.” More precisely, it integrates surface and form into space, thereby winning the power of being called an independent art. Also as an art of shaping space, film approaches architecture in two more in-depth aspects: first, the first and even the only creative content of the two needs to be found in concepts and structures, and of course the relevant methods in later production must also be considered. Two, both are troublesome and trivial, related to this, abstract. Movies must gather a large number of aesthetically trivial elements and use complex techniques to achieve small but aesthetically important scenes; similarly, in order to obtain the desired form, buildings also need to use a lot of building materials and technical support. Quantitatively speaking, the first point is correct. More time is spent on pre-production rather than shooting and post-production-in an aesthetic sense this also applies to some directors (like Hitchcock’s famous but perhaps The untrue argument is that most of the work is done when the film is being shot), but other directors, such as Antonioni, hold almost the opposite argument: the main creative work is done at the time of filming. In the preface he wrote for the film script collection from 1955 to 1964, Antonioni said: There is no film that is not printed on film. However, Kazanski’s second argument is very interesting and suitable for Antonioni. His films contain many traces of trivial and abstract processing to make spaces with no aesthetic value important.

Understanding Antonioni’s films needs to be further based on Kazanski’s theory, because his films are not only the use of architectural aesthetic values, they (especially "Night", "Eclipse" and "Red Desert") are also related The building itself and its relationship with people. Shooting architecture made the space in his movie rebuilt and changed: three-dimensional becomes two-dimensional, the color is reduced to single frequency (the work before "Red Desert"), and the movement effect in the space is adjusted by adjusting the camera position and editing Obtained, the editing also breaks and reorganizes the space. There are obvious and stylized uses of "traditional" techniques in the film, such as shaking shots, incomplete images, editing and reorganization, disrupting the continuous meaning of "images" (physical shots). At this point, they are sculptural. . All of Antonioni’s films inside and outside the building show this, and the beginning of "Eclipse" is perhaps the most striking example.

Structure and physical space

now turn to space and nature, with Monica. Two sets of shots in the two films that Witty starred in: "Red Desert" and "Eclipse" are examples. The first shot appeared 16 minutes after the beginning of the film and was about 1 minute in length. Before starting, Juliana woke up from a nightmare, walked into her son's room, turned off the robot toy that was still on, and it kept moving back and forth while the son was sleeping. Then she walked up to the landing. The white walls (red filters make them a little pink) were pierced by blue steel pipe railings and handrails, and there was a cradle-shaped chair on it. When Juliana went downstairs, the camera was taken from behind, but she suddenly stopped, turned around, wrapped her pajamas, and switched to a medium-height frontal camera showing that she was looking to the left, as if she was thinking of something. In the next shot, she was walking up, as if cold, slapping her arms, retracting her arms into her pajamas, taking out a thermometer from her armpit, and looking at it under the light. She fell into the chair, separated her legs, looked at the thermometer again, rubbed her arms, slid her hands across her chest, and placed her palms on her thighs. At this moment Hugo walked out of the bedroom, looked at the thermometer, and told her that the temperature was normal, then he leaned down, lifted her pajamas along one leg, and slapped the other leg.

There are two things that attract attention in this group of shots. One is that space not only restricts the role, but also provides a background for the role's activities, but also creates a tense or even antagonistic relationship with the role. The audience can feel that Juliana is shaking with everything around her (her horrified gaze at the "empty space") and everything in her heart. Antonioni and Tonino. Jura’s script reads like this: She stopped suddenly, holding the handrails of the stairs, as if frightened by something coming out of the floor. However, this internal and external conflict loses its meaning in the film. We can only feel what Juliana's gestures, movements and expressions convey. Another point is that the expression of desire is voluntary (Juliana is obviously narcissistic and attracted by her body) and is also resisted, as can be seen from the suffering, sickness and fatigue she exhibits. The conflict between willingness and resistance culminates when Hugo lifts her pajamas and strokes her legs: her first reaction is to resist, and then relax. In fact, this type of conflict is not only seen in this set of shots (Hugo teases Juliana, who resists and obeys), but throughout the film. From the opening scene, Juliana wearing a dark green shirt eating a sandwich next to an industrial garbage dump, to the end, Crado watched her in the shop and awkwardly lured her to her own hotel nearby. Juliana evoked two concepts in the eyes of the characters and the audience. The appearance of her body caused the conflict between her external beauty and internal morbidity, the body that caused desire as a sexual object objectively, and the consciousness full of subjective crisis.

The set of shots in "Eclipse" is the opening shot, which also explains this difference well. It lasted for two and a half minutes, from the subtitles to the beginning of the dialogue (starting with Ricardo's footage, about ten minutes). The lens creates a tension between Ricardo and Victoria, through the outline of their bodies, through the lens of stationary objects, through their movements, and through their relationship with the objects in the room. The two did not speak, and occasionally they looked at each other. Unlike Juliana's shot in "Red Desert", there is no long shot of a woman's body, and there is no fetishistic worship and voyeuristic desire for women. The camera is aimed at some parts of her body, shooting from an angle that she can't see: from behind her, her slender fingers touch the edge of the frame, move the ashtray, tap the side of the small vase, and look smooth from between the legs of the table. With her legs on the floor, she curled up on the sofa, her back to the camera. This kind of lens has no fetishistic worship and voyeuristic meaning. It is different from similar scenes in classic Hollywood westerns. Like Malvey said, the perspective of the latter is that of a certain male character. Ricardo sometimes looked at Victoria, but he looked inside the camera, which was different from the peeking between the legs of the table. Some shots showed that he could not see her at all due to the position.

Here, the architectural space and the sexual body have a subtle relationship. The layout of the picture space and the lack of dialogue between characters and other ways of communication have created a too heavy emotional atmosphere, with a tense atmosphere. Here, this lack and close attention to space makes time seem to be non-existent. Even after Ricardo and Victoria started a brief conversation, the picture still controlled the camera. Victoria opened the curtains and looked outside, but the window was like another obstacle: a transparent glass enclosed the room, and there were more man-made scenery outside, and the strange mushroom-shaped water tower always occupied a place in the lens. She looked in the mirror, her face and indoor scenery appeared in the mirror, and she backed away in fright. At the same time, Ricardo sat listlessly on the recliner, his eyes dull, he was like "a piece of furniture."

Finally, I want to return to modernity and modernism. Between the body and the space, these films caused turmoil and confusion in the tender relationship: the body—especially the woman's body—was frequently placed on the edge of the screen, or shot from behind, above, and below. The body and space are in a tense relationship, sometimes in opposition, with buildings or parts of buildings (pillars, stairwells, windows or window lattices) surrounding the characters, separating them, or covering them. Similarly, blank space, as Kaisai is called a space waiting for people to enter, also creates a tense atmosphere, and the body and space are alienated from each other. In 1931, Walter. Benjamin’s article on Eugene Atget’s Paris photos and surrealist photography pointed out: Street shots with few people indicate “a beneficial alienation between people and the environment” because they destroy the atmosphere, lack warmth, and strengthen and mutually reinforce each other between people and places. The illusion of confusing relationships allows "political-educated eyes to move freely." Antonioni's handling of space and body is the same, and for the same reason. At that moment, he was very modern. The body in front of the camera was an imaginary body, separated from the solid relationship with the place. The environment becomes unfamiliar. A space full of characters can not only become a vacuum, but also an abstract and mathematical space.

But the technique here is more complicated than Benjamin expected, because all the operating procedures are gendered and sexual. Targeted women’s bodies hinder the narrative, and they appear to stimulate thinking. The shots I discussed above, as well as many shots in these and other films, the doctor’s anatomical way of viewing is sadistic in nature, reflecting The characteristics of Antonioni's treatment of actors: control their every movement and position, their connection with space, add their own exploration objects, and occupy the actor's knowledge, without giving them any opportunity to imagine. Put Monica. After Witty was placed in an extremely stressful environment, he liberated her a little like doing an experiment, but only within the scope allowed by the development of the narrative. The conflict between control and liberation was the characteristic of all his films in the early 1960s, and it was also the source of the strong visual impact and the greatest limitations.

View more about L'Eclisse reviews