According to “No,” the answer is: you give them happiness.

Or give them impressions of happiness, as in highly Westernized images on television of hip-hop and ballet dancers and tall white families having a picnic of baguettes that nobody in Chile ate in the 80s. Of course, there is a political message behind those images , and the campaigning strategy grows more sophisticated as V-Day draws near, but the gist is the same: the people have had enough pain, so we need to feed them with fantasy. Did I say “fantasy”? I meant “hope. "

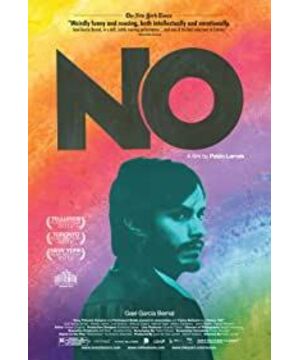

A political drama based on historical events and ironically larger-than-life premises, “No” echoes the triumphant “Argo” in its thrill, humor and craft. But unlike “Argo,” “No” is a one-man show. Impossible to overlook in contemporary hispanophone cinema, the dominating presence of leading star Gael García Bernal (“Amores Perros,” “Bad Education” and “Babel”) is as much unmistakable in the film as he is in the poster: against a palette of colors , his gaze over his right shoulder seems contemplative, charismatic and strikingly heroic.

But that impression can be misleading. “No” draws a clear, if at first subtle, line between the biopic of a hero who saves the country from a despot and the vignette of a common man who plays his part in a movement, the latter being closer to what the film sets out to do. The film is ambitious not because it deals with an ambitious whole, which is the revolutionary rejection of Pinochet's regime through a shockingly bare national referendum; rather, it zooms in on Rene (Gael García Bernal ), the mastermind behind the opposition advertising campaign, whose resoluteness is as pronounced as his lack of grandiose self-importance. The “No” campaign turns the table around and drives out a bloody authoritarian regime, but as the confetti flies high and cheers rock the streets, the protagonist walks away quietly with his son, smiles faintly,then hops on his next project: a promo for a low-brow telenovela. He is the hero of the campaign, but the film does not give him much credit. There is no speech about democracy, about media or about history, even though the power of all three saturates the storyline; there is no dramatic music score that accentuates the righteous audacity that would blaze through a conventional blockbuster on a similar subject. In fact, the film almost presents an antithesis to the Hollywood tradition. Before Rene presents his latest work to the clients in the advertisement company he works for, he always introduces the tape in a serious tone. “Today, Chile thinks about its future.” As his signature, this line mocks the hyperbole that has come to define cinematic heroism and bombastic high-talk.He is the hero of the campaign, but the film does not give him much credit. There is no speech about democracy, about media or about history, even though the power of all three saturates the storyline; there is no dramatic music score that accentuates the righteous audacity that would blaze through a conventional blockbuster on a similar subject. In fact, the film almost presents an antithesis to the Hollywood tradition. Before Rene presents his latest work to the clients in the advertisement company he works for, he always introduces the tape in a serious tone. “Today, Chile thinks about its future.” As his signature, this line mocks the hyperbole that has come to define cinematic heroism and bombastic high-talk.He is the hero of the campaign, but the film does not give him much credit. There is no speech about democracy, about media or about history, even though the power of all three saturates the storyline; there is no dramatic music score that accentuates the righteous audacity that would blaze through a conventional blockbuster on a similar subject. In fact, the film almost presents an antithesis to the Hollywood tradition. Before Rene presents his latest work to the clients in the advertisement company he works for, he always introduces the tape in a serious tone. “Today, Chile thinks about its future.” As his signature, this line mocks the hyperbole that has come to define cinematic heroism and bombastic high-talk.even though the power of all three saturates the storyline; there is no dramatic music score that accentuates the righteous audacity that would blaze through a conventional blockbuster on a similar subject. In fact, the film almost presents an antithesis to the Hollywood tradition. Before Rene presents his latest work to the clients in the advertisement company he works for, he always introduces the tape in a serious tone. “Today, Chile thinks about its future.” As his signature, this line mocks the hyperbole that has come to define cinematic heroism and bombastic high-talk.even though the power of all three saturates the storyline; there is no dramatic music score that accentuates the righteous audacity that would blaze through a conventional blockbuster on a similar subject. In fact, the film almost presents an antithesis to the Hollywood tradition. Before Rene presents his latest work to the clients in the advertisement company he works for, he always introduces the tape in a serious tone. “Today, Chile thinks about its future.” As his signature, this line mocks the hyperbole that has come to define cinematic heroism and bombastic high-talk.Before Rene presents his latest work to the clients in the advertisement company he works for, he always introduces the tape in a serious tone. “Today, Chile thinks about its future.” As his signature, this line mocks the hyperbole that has come to define cinematic heroism and bombastic high-talk.Before Rene presents his latest work to the clients in the advertisement company he works for, he always introduces the tape in a serious tone. “Today, Chile thinks about its future.” As his signature, this line mocks the hyperbole that has come to define cinematic heroism and bombastic high-talk.

Yet I imagine that the refrainment of the film from heroism stems from both artistic and ethical purposes. In reality, there was indeed a flashy “No” campaign that tried to persuade Chileans to choose democracy over Pinochet's regime, and Chileans did vote to oust Pinochet , but to suggest that the campaign catalyzed the result would invite controversy. That is okay, because given the generally ancillary role that reality plays on screen these days, the otherwise humbleness of “No” deserves a nod.

Despite the intentionally muted heroism and the many humorous moments that reveal alacrity for self-deprecation (the rainbow symbol in the “No” campaign that represents the spectrum of opposition confuses the minister, who could not decide whether his opponents were gay, the indigenous Mapuches or gay Mapuches), the film reminds us from time to time of its seriousness. And thankfully, it does so in a way that respects our intelligence. When Rene embraces his wife, who as a dissident has been in and out of arrest and police abuse, we only need to hear his one statement of purpose: Pinochet needs to go. Then, confident that the message has registered in our minds (rightfully so), the film moves on to scenes of the shooting of another wondrous advertisement. To that I say, dream on: unabashed with its vintage visuals and matter-of-fact tone,"No" hits an honest mark.

---

First published in The Amherst Student, Issue 142-23

View more about No reviews