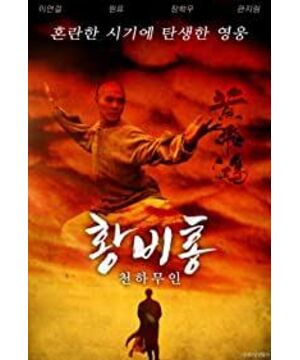

[This is the course essay of "Identity and International Relations". Since the teacher is a martial arts lover, so am I. With the national character of Kung Fu movies, the theme of this article came into being. Since this article is intended to promote the nationalist narrative (reflective, multi-faceted) in Huang Feihong directed by Xu Da, it is placed under the film review of Huang Feihong. ] Abstract: As an important genre of Chinese-language movies, Kung Fu movies have been absorbing nourishment from the idea of a "sports powerhouse" in the early 20th century from the early days of their birth, and will conflict with the national identity discourse represented by the "sick man of East Asia". Structure as a customary theme expressed in movies. However, with the change of the political atmosphere and economic development of the Chinese cultural circle, this kind of national identity discourse has gradually been weakened. In the 21st century, it is even more challenged by heterogeneous internal and external discourses, and faces the possibility of being reconstructed. Keywords: Kung Fu movie East Asian sick man self-Orientation The nationalist expression of ancient Chinese Kungfu has a wide range of influence today, which is inseparable from its combination with modern film art. Kung fu movies are the most internationally influential genre movies in the Chinese-language film world. Among the many Kung Fu movies, those "national hatred and family enmity" stories with modern China as the background have also become one of the most commonly used themes. Moreover, as an important text that carries the discourse of modern Chinese national identity, Kung Fu movies not only show that Chinese nationalism is the historical context of the modern colonial crisis, but also faithfully record the changes in Chinese attitudes towards nationalism in different eras. By consulting the literature and searching the database, the author found that the research on Kungfu movies and nationalism related topics can be divided into three categories. The first category is the analysis of the phenomenon of modern Chinese people linking sports competition with the expression of nationalist sentiment (the heart knot of the "sick man in East Asia"). There are two main paths: past domestic research mostly attributed the cause to the colonization of Western powers. Invasion and oppression, representative works include "From "Sick Man in East Asia" to Sports Power" edited by Gao Cui; but in recent years, some Taiwanese scholars have begun to try to review this from the perspective of "physical history" research and the method of rereading texts. The development of nationalist identity related to the body has been studied systematically by the associate professor Yang Ruisong of National Chengchi University, who explored the origin of the concept of "Sick Man of East Asia", and some researches on "the history of the body" by Professor Huang Jinlin of Tunghai University. book. The second category is the commentary on the plot structure, cultural connotation and market reaction of many Kung Fu movies. This type of literature is mostly seen in various domestic journals and magazines in different periods, and opinions vary from praise to criticism, but it can be regarded as first-hand information in the study of the social impact of Kung Fu movies. The third category is academic research that links Kung Fu movies with nationalist narratives. Domestic systematic research on this topic is relatively lacking. The richer one is the study on the expression of nationalism in a movie or the same series. This topic is also scattered in some monographs on the history of kung fu movies, such as Jia Leilei has been involved in "The History of Chinese Martial Arts Films", and there are some related translations, such as "Kung Fu Idol" by British scholar Lyon Hunter. To sum up, although there are relatively rich sources of data and basic research on nationalist narratives in kung fu films and films, the two are connected to clarify the nationalist narratives in Chinese kung fu films in the 20th century. Research on the development context and exploring the reasons behind the changes is still relatively weak. This article aims to make some tentative explorations on this issue. 1. Alarms: "Sick Man in East Asia", "Sports Saving the Nation" and Chinese Nationalist Kung Fu Movies are the most important Means of expression-traditional Chinese Kungfu, the reason why it can leap from ordinary folk skills to "national martial arts" and even the sustenance of the entire national spirit is inseparable from the idea of "sports saving the country" that emerged in the early 20th century, and "the sick man in East Asia" "This concept was repeatedly said during this process and became an important national identity discourse in the narratives of later Kung Fu movies. The term "the sick man of East Asia" is now often regarded as an insult to the general frailty of the Chinese people by the great powers. The West called China the "sick man". It is believed that the political theory reprinted in the Shanghai English newspaper "Zi Lin Xi Bao" in 1896 was first seen in the country, but in this political theory, the "Sick Man" (Sick Man) is only against the defeated Qing dynasty in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895. An objective description of the phenomenon of accumulating abuses and fatigue. In fact, the Chinese used the term "sick man" even earlier: Yan Fu used "China today, not even the sick man," in his "Yuan Qiang" published in March 1895 as a metaphor for the urgency and fundamentals of the reform. The necessity of starting. Therefore, the "sick man" did not originate from the insults of the Western powers at first, but a kind of loyal and rebellious voice in the autumn of the nation's survival. However, with the failure of the Reform Movement, some intellectuals felt that to save the nation, it was necessary not only to reform, but also to unlock the power of the people. At the same time, due to the spread of social Darwinism, the calls for cutting off the “root inferiority” of the people and competing with white people for racial superiority gradually increased. As a kind of everyday language with ambiguous scope, "sick man" is easy to expand explanation. Therefore, the meaning of "the sick man of East Asia" gradually changed in the early 20th century. In 1903, Liang Qichao, who was in exile in Japan, published his article "On Martial Arts," and he began to reflect on hygiene habits and traditional morality. He lamented "Woohoo! Everyone is a sick man, and his country is not a sick country!" In Chen Tianhua’s "Warning Bell", "foreigners do not call the sick man of the East, they call him a barbaric scum", which defines "the sick man of East Asia" as a term used by outsiders to ridicule and insult the Chinese. The metaphor of "sick man" has been transformed into a popular description of the weak human body in China, which has caused Chinese people to gradually understand "sick man of East Asia" as a "ridicule" of Westerners towards Chinese people. In order to change the status of the humiliated "sick man of East Asia", many people began to imitate the practice of encouraging the spirit of martial arts in Japan's reform, and regard sports as one of the important strategies for saving the country. Liang Qichao clearly expressed his view of learning from Japan as a powerful country in military affairs in his book "Bushido in China" published in 1904. The official symbol of becoming an independent film genre was the release of "Huang Feihong" directed by Hu Peng and starring Guan Dexing in 1949. "Huang Feihong" not only created a series of 77 films from 1949 to 1994, but some of the basic elements have been widely inherited and repeatedly reproduced by later Kung Fu movies: the real martial arts of hard bridges and hard horses, and the national spirit of self-improvement. The traditional morality of modesty and etiquette... But in this period, nationalist narrative is still not a common theme of Kung Fu movies, and national sentiment is still in a non-"manifest" stage in the film. The “self-Orientalized” national identity discourse discussed in the previous part is clearly combined with Kung Fu movies and has a wide-ranging social impact. It started with the three films filmed by Bruce Lee in Hong Kong. The popularity of Bruce Lee's films in Hong Kong is not only due to his own mastery of kung fu and innovative film shooting techniques, but also the high nationalist sentiment reflected in the three films, especially "Jing Wu Men" perfectly "revenge" this. The themes of traditional martial arts films are combined with ethnic conflicts. Chen Zhen broke the plaque of "Sick man in East Asia" and kicked off the sign of "Chinese and dogs are not allowed", and became a classic scene in Chinese movies. As far as the film structure is concerned, the first half of "Jing Wu Men"-from Chen Zhen returning home to attend the funeral to enduring the Japanese insults-is a process of accumulation of national hatred; while the second half is a process of intense release of hatred First, Chen Zhen took the "Sick Man of East Asia" plaque to take the initiative to fight and defeat many Japanese karate disciples, and issued a declaration that "Chinese are not Sick Man of East Asia". The killing of the Russian Hercules and the Japanese karate hall master positively affirmed the wisdom and force of the Chinese people, completely shattered the insult of the "Sick Man of East Asia", and at the same time pushed the national revenge mood of the whole film to the extreme, and also shaped the illusory screen of Chen Zhen. Hero image. Throughout this narrative structure, the image of the perpetrator of the Japanese Karate Gym as a representative of the aggressor is clear, while Chen Zhen’s anger, resistance, and ultimate victory are precisely the transfer of the concept of "Sick Man in East Asia" and the concealed idea of "Sports Power" in the aforementioned modern history. The screen manifestation of Han's resistance logic. Some critics say that this film exhibits a kind of "belligerent" Chinese characteristics: "eternal, essentialist and idealistic...absolute nationalist and racist; strongly anti-Japan". It can be said that "Jing Wu Men" borrowed the nationalist symbol of "the sick man of East Asia", applied the plot of the traditional story of "revenge", and established Japan, the largest invader in modern Chinese history, as a vent of nationalist sentiment. The "other" turned Chen Zhen into a screen spokesperson for the Chinese nation with both wisdom and courage, thus not only achieving great commercial success, but also establishing a standard reference for the nationalist narrative of later Kung Fu movies. It is worth noting that the expression of national identity discourse in this film is not one-way, but a reflection of the lack of collective identity in Hong Kong society at that time. This is the background of the popular era of "Bruce Lee Movies". Due to the confrontation between the two sides of the strait after the end of the civil war, there was widespread opposition between the "Left" and the "Right" in the overseas Chinese society in the 1960s and 1970s, especially in Hong Kong society. ". At that time, Hong Kong was experiencing rapid economic development. At the same time, there were constant struggles between the left and the right. The Hong Kong and British authorities used high-handed methods to rule, and the government had serious internal corruption. During this period, various social movements in Hong Kong were surging, and the "Cultural Revolution" in Mainland China and the "Martial Law" in Taiwan also made Hong Kong and overseas Chinese groups living in ideological cracks feel unprecedented depression and loss of belonging. People who encounter an identity crisis in reality turn to the fictional world of images to seek confirmation of their identity, and the film "Jing Wu Men" provides a virtual vent for this kind of national sentiment that is nowhere to be placed in reality. channel. This is the external factor for the success of "Jing Wu Men". The Bruce Lee-style nationalist narrative represented by "Jing Wu Men" is only the beginning of the combination of kung fu movies and national identity Chinese. As the times change, this expression of nationalism is also quietly changing. 3. Downplaying: The inclusive nationalist narrative in Tsui Hark's Huang Feihong series Tsui Hark is a leading figure in Hong Kong's new martial arts films in the 1980s. The martial arts films directed by him are full of imagination and creativity. And the representative of Xu's Kung Fu movie firstly introduced the first three Huang Feihong series that he collaborated with Kung Fu superstar Jet Li . As the new Huang Feihong series shot in the 90s, against the unchanging background of modern China, Tsui Hark reversed the simple worldview of Bruce Lee’s films with abstract opposition between Chinese and Western abstracts, and chose a more magnificent wide-angle lens. A society in the late Qing Dynasty is presented in front of the audience in a panoramic manner, and Tsui Hark’s worldview is therefore more complex and contradictory in another sense: the beauty of traditional Chinese culture represented by lion dances and Cantonese opera, and the superstition and ignorance of the white lotus religion. At the same time, there are not only gang leaders who seek refuge in foreigners abducting and selling compatriots, Beijing bullies who bully and dominate the city, but also revolutionaries such as Sun Wen and Lu Haodong. The treatment of the images of Qing officials in the film is not "face-like". Although stubborn, it also has the side of protecting the environment and the people and resisting foreigners. Similarly, the foreigners in the film are not all vicious invaders, the first part. There is a priest who has the courage to testify for Huang Feihong to get rid of the charges; although the Russian killer in the third part arrogantly believes that China must be ruled by a foreign country, his feelings for the thirteenth aunt also show his surviving humanity. In short, people, officials, foreigners-in the Chinese society of the late Qing Dynasty under the lens of Tsui Hark, it seems that every person has two faces. This diversified treatment of background figures makes traditional kung fu movies dominated by physical insults. The words and language of "Sick Man of East Asia" cannot be the subject of the series. Moreover, the entire series also reflects the director's thinking on many issues such as the roots of national inferiority, the dependence of revolutionaries on the outside world, the tension between learning from the West and maintaining traditions. The orderly blending of these multiple values not only makes the film present a kaleidoscope of excitement, but also allows different audiences to get what they want. While Tsui Hark’s panoramic narrative highlights the complexity of micro-history, it also dilutes the high-spirited nationalist passion in Bruce Lee’s films to a certain extent. Huang Feihong in Tsui Hark’s lens is a contradiction between China and the West: Huang himself is an old-school figure who obeys the rules and he is the heir of the two traditional skills of Kung Fu and Chinese Medicine, but his lover, Thirteenth Aunt, has a foreign background. When Huang was forced to come into contact with many western lifestyles and advanced technology under the influence of the thirteenth aunt, he showed both acceptance (sometimes wearing sunglasses and top hat), but also incomprehension (for learning English, taking pictures, etc.) Be impatient), and even occasionally show a repulsive side (when Baozhilin was burnt down, he angrily ordered that "foreign things" should not be used anymore). Unlike Bruce Lee's emotional, rebellious, and comforting image of Chen Zhen that Chinese people lose their sense of national identity, Tsui Hark's setting of Huang Feihong makes him more historically authentic. However, in the face of the unstoppable cannibalization of the powers and the destruction of tradition by modern technology, Huang Feihong also showed his helplessness as a civilian and a successor of tradition-he is not a representative of Bruce Lee's violent ability of the Chinese nation on the screen, but an outstanding person who still survives tenaciously in a rapidly modernized/westernized Chinese society. Traditional culture, and the self-improvement spirit that accompanies it. This change in the expression of nationalism should be intrinsically linked to the social and economic development of Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the mainland in the early 1990s and the relaxation of the political atmosphere on both sides of the strait. When the power gap between the Eastern society represented by the Chinese and the Western society gradually narrowed, the "Sick Man in East Asia"-style national identity discourse and revenge-style nationalist sentiment vented lost the external market, and Tsui Hark’s more tolerant nationalist narrative approach was right. The modern history of humiliation takes a more vicissitudes and a slightly sad epic The treatment seems to be more in line with the current social thoughts and the psychological needs of the public. If the audience in the early 1970s could find the passion to confirm the sense of belonging to the national identity in the nationalist narratives of Bruce Lee’s films, the audience in the early 1990s could recall the distant memory of national history from the series of Tsui Hark and Huang Feihong, and from The tolerant nationalist narrative reflects on the purely "sick man of East Asia" discourse of national identity. Fourth, refactoring? In the context of the new era, the expression of nationalism in kung fu movies has entered the 21st century. With the steady economic development of mainland China for more than ten years, the Chinese society has become more powerful and confident. Kung fu movies have experienced a period of low climax since the late 90s. With the activeness of new and old Kung Fu actors such as Donnie Yen, they have regained their vitality. Moreover, with the gradual increase in exchanges between China and foreign countries, the traditional Chinese film genre of Kung Fu movies has also begun to take steps to the world. For example, the Hollywood blockbuster "The Matrix" makes extensive use of Chinese Kung Fu to enhance its expressiveness. Chinese director Ang Lee shot " Oscar-winning martial arts films such as "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon" have also appeared in a large number of cartoons "Kung Fu Panda" that borrowed Chinese elements. In this new era of diversification, there are more variables for the national identity discourse hidden in the customary themes of kung fu movies for a long time. One is the challenge of individualism and postcolonialism to the narrative of nationalism. The Ip Man series is the most successful interpretation of traditional Kung Fu movies in recent years. But different from previous Kung Fu movies, in terms of plot arrangement, director Ye Weixin adopted a two-stage structure for both of the two Ip Man films: The first part is mainly about Ip Man’s home life and the contest between him and other Chinese martial artists. The second part is the battle between Ye Wen and his opponents. Moreover, Yen Zidan’s interpretation of Ye Wen is a traditional Chinese man who is humble, protects his family, and loves his wife. Wushu only exists as a hobby of his early years (part 1) and a tool for raising his family in his middle age (part 2). It does not exist consciously as a tool to achieve justice (in both Chen Zhen and Huang Feihong). And the reason why Ip Man would challenge the Eastern and Western boxers in the first part was that half of them could not bear the killing of their friends, and half were forced by the Japanese; in the second part, they were also beaten to death by fellow fighters. The righteous indignation, as well as the insult of Chinese martial arts. Although the concept of "Sick Man of East Asia" has been re-introduced here by Tsui Hark, the reason for the resistance of the screen heroes is more personal. It is different from Bruce Lee’s proactive and obviously asymmetrical nationalist revenge. Resistance is more passive and limited, and its combat goal is not to achieve the nation as a whole, but more to the protagonist’s individual righteousness. righteous. There is another detail worth mentioning: the second half of "Ip Man 2" described Hong Zhennan and Ip Man in the "tornado" battle with the Western boxing champion. It was originally a very traditional revenge-style nationalist narrative, but the director However, it deviated from the "conventional" plot development, and arranged a speech by Ye Wen at the end, which turned this traditional, revenge-style, yellow race against the white race's anti-"East Asian sick man" victory into a call for racial equality, The Western-style declaration of human rights of mutual respect and understanding was applauded and cheered by the British audience, and the national sentiment that had previously been exaggerated disappeared. The ambiguous attitude towards British colonial rule embodied in this plot treatment reflects that post-colonial nostalgia has become a popular trend in Hong Kong society. This individualistic and post-colonial way of expression is the latest development of the narrative logic of traditional Kung Fu movies in the current era, and it also poses a powerful challenge to the traditional discourse of national identity. The second is the challenge of re-encounters with the West and cultural misunderstandings in the context of globalization. As mentioned earlier, "The Matrix", "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon" and "Kung Fu Panda" are three typical Hollywood movies that have achieved success after incorporating Chinese Kung Fu elements over the years. With the exception of "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon", the other two films have achieved good results in the Chinese cultural circle, but "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon" has a high box office in North America. To explore the reasons for this phenomenon, the two films "The Matrix" and "Kung Fu Panda" only borrowed the elements of Chinese Kung Fu as a kind of "props" to advance the plot, but the plot is still about pure American superhero science fiction. Movies and inspirational cartoons, this simple combination of Western core and Eastern appearance allows Chinese audiences to find familiar things while enjoying Western blockbusters, but also allows Western audiences to discover what can satisfy their "Oriental" imagination." "Exotic" things, the result is naturally happy for everyone. But for "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon", a work directed by Chinese director Li Ang, because Li Ang is committed to restoring a Qing Dynasty society that looks as real as possible (in fact, he did this better than most domestic The director should be good), and use the most martial arts action to interpret this martial arts story (Yuan Heping's martial arts guidance), but in the script, a Westernized perspective is chosen to interpret the traditional Chinese ethical relationships of husband and wife, master and apprentice, father and son. . Western audiences may simply walk into this martial arts world full of "Oriental" imagination, but for audiences in the Chinese cultural circle, what is introduced by the perfect appearance of martial arts is a purely Western discussion of cultural propositions. It is easy to produce a kind of "familiar strangeness", and it is inevitable to feel confused and resort to rejection. The "fragmentation" of kung fu elements and the substitution of kung fu connotations reflected in the Hollywoodization of kung fu movies are the result of the misunderstanding of Eastern culture by the West, and it is also the characteristic of "Orientalism" in the original sense. When the national identity discourse in Kung Fu movies is confronted with the challenge of deconstruction and reconstruction by the powerful Hollywood movies, it is also a question of how to respond. All in all, the traditional nationalist narratives in Kung Fu movies that target the physical insults of foreigners to Chinese people have continued to evolve over the course of half a century. By the beginning of the 21st century, they have suffered from internal individualism and post-colonial discourse. , And another challenge to the external Westernist discourse. Like the changes in the narrative form of nationalism before, the current changes also reflect to a large extent the changes in people's identification concepts in contemporary Chinese society. Whether the theme of nationalism in Kung Fu movies will continue to develop, be reconstructed or gradually disappear, depends on the trend of changes in Chinese national identity on a broader social level. References: I. Monographs: 1. [English] Leon Hunter: "Kung Fu Idol: From Bruce Lee to "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon"", Beijing: Peking University Press, 2010 edition 2. Jian Heyan: "Chinese Film Concept History, Kunming: Yunnan University Press, 2010 Edition II. Thesis 1. Yang Ruisong: "Imagining National Shame: The "Sick Man of East Asia" in Modern Chinese Ideological and Cultural History", in "Journal of History of National Chengchi University", Issue 23 2. Cai Zhenfeng: "A Review of the Ideas of Bushido in Modern China", published in "Taiwan East Asian Civilization Studies", December 2010 3. Tan Chang: "The Reality and Images of a Hundred Years of Huo Yuanjia", in "Xiaokang", 2010-12 Issue 4. Wu Yun: "Popular Narrative and Metaphorical Symbols-An Investigation of the "National Image" in "Huang Feihong" Movies", published in "Contemporary Movies", Issue 1, 2009. 5. Lie Fu: " Tsui Hark’s "Huang Feihong" Series Research", published in "Contemporary Movies", March 6, 1997. Tang Hongfeng: "Ip Man 2: The Passion of the Nationality Being Seen and Dissolved", published in "China Report", No. 2010 Issue 6 7. Fu Peng: "The Writing of Nationalism in Hong Kong Kung Fu Movies-Taking the Film "Ip Man" Series as an Example", published in "Art Review", Issue 7, 2010 8.

View more about Once Upon a Time in China reviews