Unknown Time Bobonnie

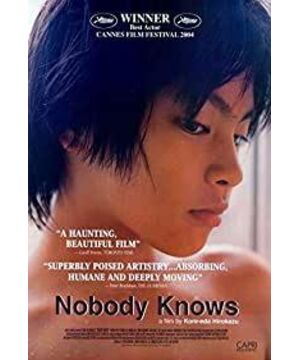

"Nobody Knows " is a film adapted from a real case by the Japanese director Hirokazu Kee . The main content is about a single mother named Fukushima Keiko, who gave birth to four children: 12-year-old eldest son Akiko, 11-year-old daughter Kyoko, 5-year-old son Shigeru, and 3-year-old daughter Koyuki. The four children come from four unidentified absent fathers. Keiko is the kind of woman: she has reached the age to look beautiful when she looks under the light. Her huge bags under the eyes make her haggard and a little stern, but her coquettish voice, girly dress, and long golden brown hair all make her People can't see that she is a "mother" or that she is ready to bear the heavy burden that life has given her. Her escape method is to hide the children in the room, not allow them to go out and go to school, hide all this from everyone, and lie to herself at the same time. Because, "I also have the right to be happy", she ran away from home twice, the first time was about a month, and the second time she never returned. She chose to live with her boyfriend in a certain area of Tokyo. The camera stayed in this narrow room, taking pictures of the lives and fate of the four children.

This is a tragedy, but there is no resentment and hatred in the movie, no crying or shouting, calm and calm temperament, bright light, lively music, no ups and downs of plot, only quiet daily description. Quite calm, but not indifferent. Only in the long-term gaze can you feel the things under this calm: deep despair, fear, strong emotions, unwillingness, longing to live like ordinary people. Crushing, transpiring, rolling, and calm again. The movie reveals an extremely powerful force: that is the life energy that strives to live, and it is also the law of life that transcends all of this.

In the movie, there are two periods of time that arouse my interest: one is when Keiko ran away from home for the first time, about a month. One section is Keiko ran away from home for the second time until the end of the film, which is about a year. Rather than saying that time itself has aroused my interest, it is the expression of time that has aroused my interest. It was Hirokazu Ee who expressed his time in a unique way.

One is the change of the four seasons. The year in the movie begins with the Fukushima family moving into a new house in the summer and ends with the children of the Fukushima family walking towards the street in the summer. I experienced Christmas, New Year and other festivals in the middle. It was Hirokazu Zhizhi who wrote the time through the change of the four seasons: In late autumn, it was obvious that a scarf was worn on the periphery. In autumn and winter, the mother has not yet returned, and the children are waiting at the window while writing in the white air on the glass. In spring, cherry blossoms are full of branches. In summer, cicadas cried out. There is no air-conditioning or fan. The house has no water and electricity. The four children stayed in the room and survived the bitter summer quietly without saying a word. Everyone has wet skin and sticky hair. At the end of summer, Xiaoxue died unexpectedly, Ming and the outsider Saxi buried Xiaoxue in the open space beside the airport. The night breeze was cool and moved their hair. It is Hirokazu Ee using traditional Japanese literary methods, such as prose and haiku, to write about the changing scenery, the changing of the four seasons, and the passing of time.

The second is the change in details. One detail is nail polish. At the beginning of the film and returning home one day and night, Keiko was in high spirits and painted Kyoko with her own nail polish. His father is said to be a music producer and Kyoko, who is eager to play the piano, has a pair of white and slender hands. The bright red nail polish makes those hands more beautiful. Keiko left home for the first time the next day, and it took about a month. The film did not reveal the exact time from the dialogue, but only featured Kyoko's hands, the nail polish was about to fall off.

One detail is the crayons. Xiaoxue likes to scribble with crayons. At the beginning of the film, she has a box of almost brand new crayons. She scribbles all day, very happy. When the outsider Saxi, a female student who was repelled at school and almost autistic, first walked into Fukushima's house, her foot was slapped by a small object, which was only the size of a bean. Crayon head. Xiaoxue, this little girl, beaming and smiling, only went out twice in the movie, was put in a box and dragged into this home, and then put in a box and dragged out of this home. Finally, it was buried together with the box. This little girl, smeared with crayons, I don't know how much time was spent on her. And this residual crayon head reminds people that apart from the time of painting, her short life actually has no other entertainment, sustenance, or possibility.

One detail is money. Keiko left home for the first time and left a sum of money for the children, about 10,000 yen. Make daily bookkeeping as an arithmetic exercise. The ten thousand yen bills are gone, and gradually, the one thousand yen bills are gone. There are only a few scattered coins on the table. In the past, a serious account was gradually obscured by children's graffiti. Finally, when Xiaoxue was killed, Ming tried to call Keiko, only three coins were left in her palm. The decrease in money tells the passage of time.

The third is real time. All movies try to convince the audience that between scene and scene, between shot and shot, the time omitted by editing is real. Everything that happens on the screen is not a fabricated story, but a real existence in a certain world. The film creators try to allow the audience to enter this complete and self-sufficient film world, believing that the narrative time and the objective time are synchronized. In order to get the "real time", Hirokazu Kee used a "stupid method": the filming time of the movie took a whole year. With the patience and patience of the documentary creator, he waited for his world to take place, build, transform, and mature slowly.

Therefore, the children in the movie have truly grown up by one year. Ming's actor, Liu Le Yumi, grew up from a twelve-year-old boy to a thirteen-year-old boy. From childishness and jerky to maturity, the camera records the whole process. In almost every scene, the children grow up slowly. This change is imperceptible to the naked eye, but it is very clear. Every second is different, because they are real lives.

The room in the movie, rented by the crew for a year, can clearly see how a fresh and tidy little house has slowly become dilapidated and dirty because it lost its mother, the soul figure. The plants on the balcony that the children planted in the beverage bottles are also true spring and fall, experiencing growth and desolation. The children who used to be well-fitted, brand-new clothes, slowly worn out, shrunk, and became cramped. Because no one was trimmed, their hair slowly covered their necks and eyes like weeds.

I think writing time like this is very powerful, because:

First, the time in the movie is aesthetic time. This way of passing time is beautiful, it is no longer a lonely time, but a lot of attached things are added, and it is time to watch and taste.

Secondly, the time in the movie is the time of gaze. Use extremely meticulous, subtle details to write about the passage of time. If the audience does not use all their attention and watch patiently, they will not know why. The movie invites the audience, just like the people in the play, to breathe quietly and stare quietly. And when you stare at that world for a long time, that world will turn your head to stare at you. As an audience, the inner world is quietly opened.

Sometimes, in the constant repetition of daily scenes, in the passage of day after day, the audience may even feel that "time" seems to have stopped. Yes, because these forgotten children are in a corner where no one knows, their fate is not cared about, and their time is no longer important. This "stagnation, stop" time is their time.

Thirdly, the time in the movie is time full of emotions. In this movie, the tool for measuring time is no longer a precise number: one day, one month, one year. For a girl, how long does it take for the nail polish to fall off from bright and dazzling? It can be said to be twenty days or one month. The brilliance does not lie in the "precision" of the time, but rather the ambiguity. When you start to guess like this, the girl's life is quietly connected with yours.

In this way, the movie requires the audience to use their own life experience to echo the movie and participate in the movie. In such a movie, time is not an element of a play, nor is it a cold number, but a full character. Time has become an emotional, growing, and tangible character.

At the same time, time has transcended the role and has become a rule. At the end of the movie, Ming went to the back door of the convenience store to wait as usual. The kind clerk gave them the expired food, while Kyoko, Shigeru and Saaki were waiting for him on the other side. The four people walked to the street together, and Mao went to the vending machine and the coin phone to look for the change that others had left. He was delighted that he had picked up a coin. After life and death, these children live as before, seemingly indifferent. And this indifference is writing about the cruelty and greatness of time. The usual peace, which writes out the essence of time, is the law of life.

View more about Nobody Knows reviews