Robbe-Grillet: The Metaphorical Structure in "Last Year in Mariambad"

Author: Linda Dietmar, Boston: University of Massachusetts

Source: boundary 2, Vol. 8, No. 3 (Spring, 1980), pp. 215-240, Published by: Duke University Press

Translation: Charles

Note: 1. [] is the translator's note, () is the paper's author's note.

2. The Chinese and English correspondences of the original novel quoted in the thesis are not clear, and the translator has limited familiarity with the text of the novel "Last year at Mariambad". Therefore, some parts are translated in the English cited in the thesis, and the remaining translations are translated by Shen Zhiming. . [Rob-Grillet: "Last year in Mariamba", translated by Shen Zhiming, Nanjing: Yilin Publishing House, second edition 2007.7]

I

Robbe-Grillet’s review articles indicate that he is a powerful opponent of the dominant literary tradition and a supporter of new French novels who are keen on writing. However, despite Robbe-Grillet's conscious polemic position, he did not clarify what the new novel is to accomplish. "For a New Novel" and his other articles are not a manifesto or guide to his novels and movies, and they may even be quite misleading. 1 In particular, the concept that "new" novels are "objective" eliminates all metaphorical and allegorical allusions [allusion], resulting in a misunderstanding and misinterpretation of his texts. His most frequently quoted article "Nature, Tragedy, Humanism" ("New Fiction", pages 49-75) believes that metaphors and allegories are anthropomorphic projections, which create a mist of vague meaning. "The Future of Novels" and "On Several Outdated Ideas" ("New Novels" pp. 15-24, pp. 25-47) put forward the same argument. Things are just "out there." The meanings that people find under the surface are just some elucidations [inventions], which give a neutral, meaningless universe with continuity and meaning. (This position echoes Ortega y Gassett’s call for "dehumanizing" art, that is, the elimination of metaphorical resonance and subterranean communication.) Robbe-Grillet on subjectivity and psychology His critique, and his insistence on "neutrality," encourage readers to treat his own descriptive passages as detached, unsentimental records. His position, as a result, locks some readers into what Roland Barthes calls "thing-ist" [chosiste bias, chosiste, literally "thing-ist"], which ignores his artistic imagination and subjectivity feature.

In an early and influential article, Bart encouraged readers to accept Robbe-Grillet’s manifesto with reasonable will. Bart believes that Robbe-Grillet's novels only focus on the visible surface of things. He stated that Robbe-Grillet deprived the objects of "all metaphorical possibilities" and regarded them as pure phenomena, "there is no alibi, no resonance, no depth." 2 Note When it comes to the connection between Robbe-Grillet’s concept of "being" and Heidegger’s philosophy, Barthes provides Robbe-Grillet with a philosophical context that encourages chosiste interpretation, which diverts readers. Direct value judgment of the text [evaluation]. In his preface to Bruce Morissette's " Les Romans de Robbe-Grillet " (Paris: Midnight Press, 1963), Barthes did acknowledge the humanist Luo Ber-Grillet exists alongside him as a "materialist" [chosiste], but because his preface mostly focuses on Robbe-Grillet’s technique, and because Barthes concludes: In this novel, The meaning is finally suspended—not only hidden, but he further downplays the humanistic dimension of Robbe-Grillet's art.

Barthes's position has led to a great deal of research, which attributed Robbe-Grillet's novels to specious neutrality and detached representations of surface objects. 3 Olga Bernal's " Alain Robbe-Grillet " [ Alain Robbe-Grillet ]; "The Absence of Novels" [ Le Roman de l'absence ] (Paris: Galima Publishing Society, 1964) is an interesting variant of Barthes’s position. Bernal also valued Robbe-Grillet’s claim of neutral objectivity, but because her explanation turned to Husserl, Merleau-Ponty and Sartre, she believed that Robbe-Grillet’s meaning "Rejection" is more active than the Heideggerian separation [separateness] noted by Bart. Starting from the same premise of "physical nature", Bernal is critical of Robbe-Grillet, while Bart is complimenting. She believes that Robbe-Grillet's metaphysics of "absence"-she believes that the lack of humanistic involvement [engagement]-is a matter of choice. Bernal admits that the modern experience of nihilism makes this "rejection" understandable, but she blames Robbe-Grillet for his negativity, because the moral "absence" is not what a person can have against the phenomenal world. The only reaction. 4

Fortunately, other readers have been able to withstand the pressure to agree with Robbe-Grillet and Barthes. Morrissette's excellent analysis of Robbe-Grillet's work is particularly important. Morissette resisted uncritical interpretations of "chosiste". He pointed out the contradiction between Robbe-Grillet's theory and practice, and believed that the objects in Robbe-Grillet's art are the "support" of human emotions, which are meaningful and lyrical. His convincing interpretation inspired Barthes-as a "partner"-a rich appreciation of the depth of the work-in the preface of his book to Morissette! Morissette's phrase "subjective objectivée" ["la subjectivité objectivée"] attempts to calm the debate about Robbe-Grillet's objectivity. However, although this concept can lead to an interesting analysis of Robbe-Grillet's subjectivity, Morissette has not fully developed it. He did not completely deny the "materialist" approach, but allowed Barthes's position to coexist with his own position, and at the same time cultivated sensitivity to the existence of metaphor in Robbe-Grillet's works. 5

Robbe-Grillet's similar independent appreciation of the psychological resonance of object processing and the depth of metaphors has formed other studies of his works. Among them, George H. Szanto's "Awareness of Narration" is famous for his attention to Robbe-Grillet's narrative consciousness. Robbe-Grillet’s narrative consciousness is a psychological entity, which determines the shape and mood of each of his novels. 6 Sauto distinguishes between Robbe-Grillet's so-called objective model and the resulting absolute subjectivity [subjectivity]. He believes that this subjectivity stems from Robbe-Grillet's way of attracting readers. Because it relies on the reader's high awareness of their own imagination activities, it triggers an interpretive transaction that is different from ordinary metaphoric communication. According to Santo, Robbe-Grillet's objects "suggest"; they are not "identical." They are related to Eliot's theory of "objective counterparts", but unlike metaphors, they do not trigger corresponding emotions [parellel emotions].

Like Morissette's "subjective objectivity", Santo's "suggestion" provides a new expression, but it does not completely resolve the dispute about Robbe-Grillet's objectivity. Robbe-Grillet’s subjectivity actually reveals the self through implication and equivalence [equation]. It allows his audience to participate in both a directed explanatory process (Santo's "hint") and a metaphorical connection. This dual participation explains the unique subjectivity he projected. Nevertheless, the important point is that his art is not "materialistic". Neutrality, in the final analysis, cannot exist in narrative art. Meaning inevitably radiates from the interaction [transaction] involved in any expression. Both words and images are suggestive words that produce expression and resonate. Robbe-Griller may be right. He thinks that our universe is just "out there" and does not carry any designed meaning, but he mistakenly believes that artifacts-an imaginative placement Behavior-can get rid of the shell of meaning. He may be right to refer to "new novel" as "new" (indeed, its creative use of dismantling and synchronic reorganization is typical of postmodern imagination), but this kind of innovation is difficult to get rid of suggestive content .

In fact, it is this false emphasis that explains the difference between theory and practice. Because although the literary "performer" [cast] Robbe-Grillet rejected the "intervention" of existentialism and the suggestive content of traditional European novels [allusive content], his impulse for objectivity and innovation was first expressed. Kind of philosophical orientation. His argument is based on the belief that science is the necessary and only basis for precise knowledge and, therefore, the basis for progress. He criticized metaphorical thinking, not that it is a bad thing, but that it is a conservative force that leads to despair. He believes that the writing of metaphors relies on layers of correspondence, which hinders accurate observation, leads to contemplation of [Beyond], and at the same time makes us blind to the nature of the world [nature]. "Science," he wrote, "is the only honest way for man to explain the world around him" (New Novel, p. 70). However, science is neither as objective as Robbe-Grillet said, nor is it less ethical and progressive. The reproduction of the perceived reality does not guarantee progress, and human perception cannot be separated from preferences and associations. Robbe-Grillet attributed absolute objectivity to "world" and "things" without considering the transactional nature of perception. When we see or remember objects, just as we imagine them, we provide explanations.

Whether it is literary creation or receiving, things cannot exist independently of human beings. At least, as long as they still rely on traditional language, this is impossible. The symbol system we call "language" uses phonetic entities to elicit explanatory associations and multiple meanings. Literary experience consists of an interactive process in which the author, one or more narrative voices, and readers all participate in shaping meaning from verbal materials. Therefore, Robbe-Grillet’s narrative expresses an inevitable tension between the seemingly objective form and the strong subjective statement. Although he tries to limit his work to a world that may exist independently of human observation, his work proves the fact that man cannot escape subjectivity. In his works, rigorous precision coexists with the gradually emerging levels of irrational, repressive, and passionate human experience. As we gradually understand his narrative point of view, it is clear that his attention to the seemingly scientific appearance of things is not a sober examination of objective reality. Rather, it is a compulsive effort to distort or avoid the facts, originating from an inexpressible passion.

Theory and practice do not match in Robbe-Grillet's novels and films [meet], and if this separation had not inspired and shaped his work, this fact would not arouse comment. He objects (for example, people in the "snapshot set" [ Snapshots ] boarded the escalator, or "Voyeur" [ at The Voyeur ] in Matias string set) and meticulous attention to the use of language, as if it's just Pure allegation; however, even though his words line up information in a seemingly calm way, they accumulate tension and excitement. There is no doubt that Robbe-Grillet’s writing carries a strict focus on accuracy and objectivity, but the results of his efforts are not similar to the scientific accuracy he insists on. ( The shadow in Jealousy [ Jealousy ] is full of passion and meaning, and the "centipede-squashed" [centipede-squashed]-conveniently, in the form of a question mark-has a clear metaphorical resonance. "In the Labyrinth" ", using a grid of endless snow-covered streets in the city, attributing indifference to the city, and mystery to the persistent pursuit of the soldiers.) The tension and excitement created by Robbe-Grillet depends in part on the plot. Fragments, these fragments conceal information and use threatening situations to attract viewers’ attention. But most importantly, the tension and excitement came from the complete separation between his apparent objectivity and the emotions he aroused. Words are never purely referential. Robbe-Grillet’s lens arrangement and setting [inventories] reveal changes, contradictions and changes, which are the main events in his narrative. His so-called objectivity is not an epistemological method, but a trick. Because it conceals and suppresses things, and highlights the tension between things and people. The troubled consciousness, in an effort to impose objectivity on materials that resist it in nature, became the protagonist of Robbe-Grillet.

In fact, the publication of the Robbe-Grillet Symposium in Cericy in 1976 showed the change in his own view of metaphoric communication. 7 In this case, he acknowledged the metaphorical nature of his work, and by doing so, he freed his readers to explore the resonance of the work in depth without involving them in unnecessary arguments. My own article—it was originally to refute his claim of objectivity, and there is no need to argue about it anymore. My original claim—that his art is highly subjective and metaphorical—has not changed. Because the metaphorical pattern is particularly evident in "Last year in Marienbad", the analysis of this movie-novel [cinéroman] is particularly instructive. 8 The esthetic and psychic [the esthetic and psychic] intersect in a particularly clear way in this work, both as the carrier of epistemological exploration and as a commentary on the exploration. Together, they express the desire for creation and certainty, as well as the doubts about the process of their production.

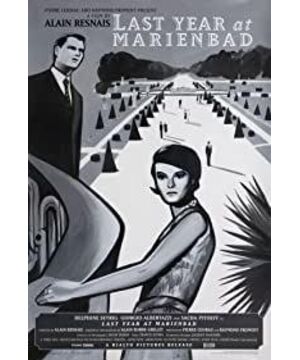

This article will continue to explore the relationship between form and theme in "Last year in Marienbad". Robbe-Grillet's thematic attention to exploration and trapping is obvious, of course, in the background setting, characterization and plot fragments of the work. However, more importantly, the structure he imposed on the material. Both the movie-novel and the movie use the concepts of exploration and trapping to determine the organization of the work. Robbe-Grillet's narrative form developed the function of metaphor and expressed painful doubts about the validity of the transcendence he tried to affirm. The fact that "Marion Bard" exists in both the printed text and the film adapted from it does not change its core expression. Words and films are different conveyers of meaning, but Renai's version is very faithful to Robbe-Grillet's text and retains the meaning of the verbal material as a whole. Even if Renai's taste and personal considerations caused him to modify the text, the changes he made also enhanced and refined [purify]—not changed—Rob-Grillet's picture [vision]. 9 (In the following discussion, I will point out the difference or connection between the text and the movie at any appropriate time.)

II

The concepts of labyrinth, trapping and resisting possession are very prominent in "Marianbad". The myth of the labyrinth dominates the entire structure of this work, and the action and the physical space surrounding the action repeatedly illuminate the myth. Once the camera leaves the credits (showing that they are well-designed and lifeless) and slides along a corridor, it defines the space in which it moves as a maze. It scans through frames, doors, windows and corridors, giving the architectural details listed by the sound of X a visual form, and its suggestive treatment of light establishes the scene description in Robbe-Grillet's early days. The atmosphere shown in:

After the credits are over, the camera continues to move forward at a slow speed, moving at a constant speed along a long corridor. People see one side of the promenade, which is quite dim, illuminated only by light from the windows of equal compartments on the other side. Without the sun, it may be near dusk, and the electric lights have not yet been lit. Although the windows are invisible, the places illuminated by the equally spaced windows are brighter, and the wall decorations are clearly visible. ["Marianbad", pp. 24-25]

The dimness of the setting creates a feeling of vagueness and gloom, and the alternation of light and dark areas suggests the possibility of entering a brighter, unexplained external space. In the film, X’s description is accompanied by the lens sliding along the gallery, while in the text, X’s monologue predicts this sliding and shapes our subsequent impressions. The two versions are very close. Both show a part of the maze, tell of more [tell of more], and create an impression that the maze extends to an unknown transcendence [Beyong].

Repeated attention to mirrors and the actions captured in mirrors shows that knowledge is often indirect. Robbe-Grillet’s mirror blurs the distinction between objects and their mirror images, and adds space by reflecting images. Just as the camera leaves the credits to show their frames [their frames], it is also far away from a couple in conversation to show that we are just watching their mirror image. Mirrors are usually dark, and their mirror images are dull. Some mirrors are made up of small squares, which further refract the field of vision and make the sense of infinite retreat of space become obvious. The camera can present reality and mirror images in a direct and instant way. It can provide an instantaneous reference [instantaneous documentation] on how visual traps [trompe l'oeil] and baroque decoration can cause spatial chaos. In the infinitely regressive colonnade, gallery, rotunda, and on the checkerboard pattern of the floor, the lens of the two checkers players is a particularly clear picture-illustrating the pattern with regular patterns. How the plane gets the depth of infinite retreat (Marianbad, picture, p. 43). Even for the garden, despite its obvious openness and bright light, the result is still a confusing enclosed space. Just like this hotel, this is a road network with no way out. Its geometric simple design conceals a lot of possibilities.

Both movies and text allow us to explore space in an orderly manner through visual movement and its verbal equivalents. For example, at one point, Robbe-Grillet instructs the camera to pull back and draw A on a garden path. The gradually widening view draws attention to the length of the path and the maze-like nature of the garden. To emphasize the trapping of A, Robbe-Grillet elaborated on the sequence of its unfolding: “A tried to escape again, turning in the opposite direction to her first turn, but she gave up again” (Marian Budd ", page 74). Throughout the film, the continuous and apparently aimless movement of the camera and the characters in the labyrinth-like space shows that the residents of this space are lost in its passages. This narrative fascinatingly traces corridors, galleries, and rooms. Their sole purpose seems to be to enclose the space and lead to other similar spaces. These characters seem to move in these spaces without any physiological characteristics that usually accompany human movements. Their arms do not swing, and their heads do not rise up and down [bob]. Their movement is like being transported in a cart, without obvious will and purpose. A is the only character whose body occasionally expresses psychological tension or desire, and even her movements are largely iconic [emblematic]: she either sways or freezes [freeze] into incoherent emotional expressions. Against the background of a supporting role who performs trapping of [mime] like a pantomime, in a space where trapping is implemented, A is acting like a pantomime and struggles to break free.

What the camera achieves through follow-up and zoom out and through mirroring, the soundtrack is achieved through its own form. At first, an interfering sound made X's voice indistinct; two identical but intertwined soundtracks obscured his voice, until the two were recombined into one. This movie specifically demonstrates the necessity of auditory adjustment [auditory adjustment]. The lips move silently, and the dancing couples move with the inner melody, out of sync with the soundtrack that accompanies them. When an amphitheater collapses, the soundtrack records the gushing water from [register]. When a small band performs, the soundtrack is accompanied by organ music. This substitution [displacement] questions the evidence use of the reference system [documentation]. They provide an auditory version of the metaphor of loss, which is triggered by many possibilities. The dialogue elaborated on the same metaphor. Fragments of the conversation are repeated with slight changes, spoken by different characters. They repeatedly told fragments of events—a rumored love story, an anecdote about the freezing of a hotel pond, a woman begging a determined suitor to keep quiet, and so on. At different times, the same dialogue seems to be participated by different characters, but never gives a complete version of any alleged event. As whispers, silence, and nonsense dominate, the possibilities increase exponentially. The meaning of these words, like the meaning of the visual material of the film, depends mainly on guesswork. Readers and viewers find themselves roundabout in the coherence they seek.

Therefore, when X's monologue becomes clear, it does not clarify anything, it is appropriate. What seemed to be a technical obstacle at first, turned out to be another dead end in search of continuity. X’s voice lists the observations with a series of roundabouts [in a meandering succession], but to no avail:

I once again-walk forward, through these living rooms, corridors, in this building of the last century...-corridors are connected to the corridors, endless...-silent, no one, decoration The stuff is bloated...——The carved door of the frame connects the rooms and the corridors. The corridors across the corridor lead to other empty living rooms, which are covered with many decorations of the last century. ……["Marianbad", p.24]

Different versions of descriptions appear repeatedly—a language that is babbled, melancholy, and rhythmically translated into a spatial maze. Like visual images, X's monologue insists that "there is no escape" (page 36). The same words continue to reappear in slightly different combinations, eliminating the traditional syntactic structure. Punctuation does not categorize or organize; it merely lists and indicates rhythmic pauses. As the lens arrangement and context lose their traditional functions, they have a new meaning: speech fragments, repetitions, and variations constitute the similarities evoked by the visual maze.

Robbe-Grillet described X's voice as "slow, rhythmic, and warm, but with a certain neutrality without emotion." ("Une certaine neutralité," French version, p. 24). The word "certain"] may blur the contradiction between warmth and lack of emotion, but it does not eliminate it. Robbe-Griller avoids explanation, implying that the contradiction cannot be resolved. X is the simultaneous dramatization of two modes of being contradictory [mode of being]-emotional and calm. Such contradictions abound in "Marianbad" and acquire a mysterious and even metaphysical dimension. For example, although the bleak magnificence of the setting inhibits its richness, it also creates an illusion of receding depth, and therefore, an illusion of escape. Claustrophobia coexists with a commitment to transcendence. Black and white films also support opposition, but they are not stated. "There are some extremely clear details,..." Robbe-Grillet wrote, "but it is not clear what kind of light source caused these strange effects" (Marianbad, p. 22). The contrast between darkness and brilliance became obscured and mysterious, because Robbe-Grillet noticed the singularity of this effect, but did not explain it. As a result, the dome ceiling becomes obscured in the dark, while its decorative top is still mysteriously dazzling. Similarly, when the audience in the hotel theater is “illuminated by the performance they are watching” (Marianbad, p. 22), the emphasis is on “performance” ["spectacle"] as "illumination" ["illumination", also The source that has the meaning of "revelation" (rather than using footlights as a light source) implies a spiritual [inspirational] experience that transcends pure matter. 10

Although light has spiritual qualities, and although mystery may imply a transcendence [Beyond], and therefore, also hints of hope, the physical structure of this hotel is still depressing. Its architecture seems to impose a suffocating purposelessness on its residents:

Man: ...I can't stand this silence anymore, these rooms, these whispers, you keep me in...

Woman: Keep your voice softer, I beg you.

Man: These whispers are worse than silence. You keep me inside. This life is worse than death. We live here side by side. You and I are like two coffins, two coffins buried side by side under the dead garden.

["Marianbad", p. 33]

This is a world where characters are eager to escape but have found nothing. Its inhabitants seemed destined to be bound by a deadly magic. Just like their domino game, their world is "a perfect labyrinth, a tortuous road made up of futile complexity" (Marian Bard, p. 140, italics added by the author of the paper) . This conquest of life force becomes obvious when we compare the world of Mariambad with traditional paintings that also have magnificent scenes. For example, Bellotto [Bernardo Bellotto, 1721-1780]’s "Schonbrunn Palace" (1759-1760) shows similar design forms and magnificent proportions. His courtyard has elegant figures and is dotted with neatly manicured bushes. Even his attention to perspective and light and shade is strikingly similar to Robbe-Grillet's. But Bellotto also depicted gardeners in shirts and, in front of the palace, ordinary citizens engaged in daily affairs. Instead, Robbie Grillet closed his world. He never showed that the door of the hotel was open to another world, and he never allowed ordinary people to enter the courtyard. Both works use elongated shadows cast on the gravel, but when Bellotto studied the patterns created by the afternoon sun, Robbe-Grillet depicted a garden where people's shadows cast on unshadowed shrubs. Cong (picture, "Marianbad", p. 96). Strangely, Robbe-Grill questioned the physical existence of the world he portrayed, not the physical existence of his characters. His interests are magic and mystery, while Bellotto's interests are optics and social.

III

Inevitably, "Marianbad" attracts readers and viewers to find some dominant principles that can rationalize unexplainable phenomena. The hotel was filled with magical hypnosis [bewitched somnambulence], which triggered a search for the force-possibly an evil force-which casts magic on the characters. Robbe-Grillet’s publicly proclaimed socialism and his naming of the opening play "Rosmer" ["Rosmer"] imply a specific social interpretation. Although the plot of "Rotherm" is not like Ibsen's "Rosmerholm" [ Rosmerholm ], its suffocating atmosphere and its era-characteristic stage and costumes echo Ibsen's destruction of bourgeois traditions Sexual assault. Therefore, it is reasonable-to regard the hidden power of the hotel as an invisible social pressure, which denies the generative thrust of life [the generative thrust of life]. However, apart from X, no one questioned or even explored such obvious social constraints in the hotel, and even X cares more about A rather than restricting her society. He separates the individual from society and politics, implying a psychological or metaphysical interpretation of the work; it directs our attention to the strength and vulnerability of the individual, rather than nourishing [nourish] their social structure. The social significance is still only hidden in "Marianbad".

The protagonist’s name, appearance, and role [role] draw attention to the archetypal human [archetypal human]’s attention to gender roles, good and evil, life and death. The image of M embodies the power, threat and control of men. X tries to persuade A to leave the hotel, which is inseparable from the competitive male struggle between him and M. Here, we see the traditional love triangle with potential metaphorical meanings. We can interpret this story as a lover trying to take passive resistance A ("A" stands for "love" [l'Amour]?) from her husband M ("M" stands for "husband" [le Mari]?) Take away, or as a stranger, X ("an inconnu" [un inconnu]11) tries to assault a woman, or conversely, free her from the shackles of society. 12 More broadly, X can also be a liberating life force, trying to drive away a threatening death ("M" stands for "death" [la Mort]?) or a ranger knight for another sleeping beauty -A feminine embodiment of love, secular or sacred-and a mythical battle with a demon. Although the work can support all these interpretations, the first two are the most unsatisfactory. The metaphorical content of "Marianbad" is not so much about monogamy and social constraints as it is about a struggle beyond destruction, in a broad sense.

Robbe-Grillet's treatment of M underscores his focus on fighting a destructive, possibly demonic, power struggle. Although M is only described as a 50-year-old man, fashionable, tall, and gray-haired (Marian Bud, p. 36), the power he gave to M is supernatural, emphasizing his evil nature, and Not his maturity. In the segment about the Nim game [the Nim game, a type of game related to game theory], M's power is most obvious, which is a game he always wins. 13 Like the aforementioned unexplainable illumination [illumination], the mystery of his intelligence control is disturbing. The plot of the game evokes a recurring archetypal fantasy of death and the devil's preference for playing games with humans. This kind of game is usually a game of dominance, not a game of luck. ( It echoes Bergman's 1956 " The Seventh Seal " [ The Seventh Seal ], which is particularly eye-catching.) Although Robbe-Grillet described M as Piteoff [original Piteoff, with Mistake, it should be Pitoëff, that is, Sasha Pitoev, who plays M in the film. The following translations are all revised to "Pitoev"] Older and paler, but Pitoev's striking performance and appearance reveal the essence of Robbe-Grillet's ideas. Pitoev's scrawny face, protruding teeth, and sunken eyes reminded of a dead head; his skinny body and chilling smile almost carried the breath of the underworld. He transcribed M's witchcraft into clearly visible terms. M is the one who provides X and A with the authoritative version of the allegory about the statue. This scene is ironic, echoing Robbe-Grillet's own opposition to projecting inappropriate meanings on objects. However, since the factual information provided by M indirectly referred to a trial of treason, the metaphorical meaning became nowhere to escape, and M's seemingly objective statement acquired a chilling quality.

Whether we read or watch "Marian Budd", supernatural thoughts are inevitable. The visual symbols of this movie have the advantage of immediacy, but they have not changed Robbe-Grillet’s original idea:

In this closed and suffocating world, people and things seem to be victims of some kind of magic, as if they were driven by an irresistible temptation in a dream, trying to change this kind of control and trying to escape. It was a waste of effort. [Original note: "Marianbad", page 16, underlined by the author of the paper]

The people living in this world seem to be walking dead, dancing their own version of the "skeleton dance" [La Danse macabre]. The dance scene vividly illustrates the magic that is implied. Stiff, indifferent, and almost lifeless, the dancers changed positions in the hall, forgetting the discordant music that accompanied them. Their bodies are frozen in the traditional dance poses, and their movements are like being teleported by some mechanical device or like rows of shadows projected by a magic lantern. Throughout the entire "Marion Bard", the timeless and formal elegance of the costumes elevates the characters above the ordinary. In those moments of high tension, Selig's costumes have acquired unique symbolic value. When escaping in the garden, she wore a dress with fine and soft wings. In a rape scene, a bright white tight-fitting robe studded with white feathers. In a tense night encounter, she wore a dress with soft wings. A long black cloak with black jade feathers wrapped her horrified face. 14 Pantomime-like performances and costumes create a highly stylized picture of a closed world controlled by its own rituals.

Photography and editing enhance the strange mystery of this world. Characters appear and disappear in a different way from ordinary experience. When the logic of a given set of lenses requires them to appear from one side, they appear from the other side, and the camera often approaches them indirectly through confusing specular reflections. The camera seems to indicate that the mirror is not impenetrable. It echoes the use of the mirror as the gate of the underworld by Gokdo, and implies a supernatural interpretation of the events it records. In the dim twilight, death and supernatural hints produce a gloomy and threatening mood, while the complex design of the Baroque decoration itself conveys tension and anxiety. Cameras, lights, and decorations are all metaphors for emotional content. For example, in A’s room, as X’s sense of urgency and A’s rebellious mood became stronger, the decoration became more and more gorgeous (original note: see picture, "Marion Budd", pages 93 and 135) . Baroque drama pays attention to depth and impenetrability, its tortuous fixedness, and its elegant form expresses the mystery of the visual concept and the contradictory desire. Because these mysteries and longings cannot be explained or solved with natural expressions, and given the scary background surrounding them, they evoke a supernatural explanation among readers and audiences.

In his book Le Cinéma fantastique , René Prédal provides a useful expression of the supernatural phenomena we see in Mariambad. 15 Although Predal mainly studies what we call "horror" movies, his discussion of "Marionbad" in the context of traditional zombies, vampires, and aliens expresses Robbe-Grillet's Deep thinking about non-material and prototype. Predal believes that the "dream" film creates a world completely separated from materiality, a world of pure mental state, and a projection of the author's fantasy. In "Marianbad" he identified the theme of illusion, the theme of the trap of death bargaining in a vast expanse of mockery, and the theme of dark, forbidden association with demonic forces. Although "Marion Bard" is not separated from materiality, its treatment of material involves mental states and supernatural themes, and does not involve the solidity of specification-this is what Henry James thinks The core of classical realist novels. The camera, X's monologue, X and A's focus on the use of objects as evidence are mainly used as non-material projections to explore matter. Robbe-Grillet's main interest lies in producing narrative materials and explaining their psychological activities. Predar correctly described Robbe Griyer's surrender to the "Alchemy of Appearance" in "Marionbad", while leading his audience to "a land full of miracles"-a land full of images and illusions. And the land of imagination.

Robbe-Grillet's illusion does not only include his allusions to labyrinths, love triangles, and possessive fantasies. He drew on quite a lot of additional metaphorical content, and if there is any difference, it is that it is more significant [powerful] because it is not specific enough. For example, the Baroque style of "Marianbad" constitutes this metaphorical content. Marcel Brion's essay on Baroque and sports aesthetics provides an excellent analysis of the psychological state expressed by Baroque architecture. 16 In particular, Brion pointed out the desire for transcendence expressed by Baroque architecture, the passion and anxiety it combines, and the sublime anxiety and hope mixed in its tempestuous atmosphere. He pointed out that the Baroque structure promotes vivid fragmentation, deformation and fracture in different directions. The most important thing is that he believes that this building is a background of ritual worship, a background of complex and serious rituals-it stems from the love of life, celebrating death, and trying to dispel the power of death. When we apply Brion’s analysis to Marienbad, the appropriateness of the Baroque style becomes noticeable. The funeral atmosphere in the hotel conveys disturbance rather than calm. Its grandeur, fragmentation, complexity and tension give enthusiastic resistance and suffocating melancholy a plastic form. As Brian pointed out,

Ambition and lack of will [l'aboulie], worries and willingness for power, worship of action, and doubts about the cause and effect of this action, together constitute a mixture of impulse and hesitation. This mixture constitutes The essence of "Baroque" ["l'homme baroque"] [le fond]. ("Marianbad", p. 22)

The power that Brion mentioned was particularly clear in Marienbad. Both the text and the film express a strong desire for freedom, self-realization, and eternity through them. Rob-Griller quoted Unamuno's "The Tragic Consciousness of Life" (1912) at the end of his article "Nature, Humanism, Tragedy," and this is not accidental. Although it is not immediately apparent, the pain and longing that are the foundation of all Robbe-Grillet's works are similar to the deep pain and longing that inspired the metaphysical exploration in Unamuno's works. The strong desire [violence of aspiration] typical of the Baroque style is a necessary response to skepticism, which neither Unamuno nor Rob-Grillet has gotten rid of. As Christine Brooke-Rose pointed out, at the core of Baroque vision there is "systematic doubt about the validity of appearances, and this suspicion is manifested in excessive attention to appearances." "17 Robbe-Grillet's commitment to the accuracy of "science" coexists with deep doubts about the usefulness of accuracy. A careful inspection of the hotel’s buildings, gardens, maps and weather records will never bring certainty. X’s use of evidence to prove that his story also fails to bring conclusions: “Last year’s” snapshots, pictures on mantelpieces, shoes with broken heels, or broken pearl bracelets contain powerful metaphors, but they don’t. Provide any evidence he wants [documentation]. The so-called events seem to happen repeatedly in different and even contradictory ways. Despite the systematic inspection, neither X nor his audience can organize the details of "Marian Budd" into a coherent diagram. "Excessive attention to appearance" became a ritual, confirming the need for understanding and control, not their realization. 18

IV

The state of doubt is painful; it cannot be the permanent resting place of the human mind. Sooner or later, a leap of faith is necessary. In Robbe-Grillet's work, this leap means the production of new narrative materials—new changes, new possibilities. Robbe-Grillet and his protagonist prove the coexistence of skepticism and faith. They question the materials that have been invented and sometimes discard them, but they also celebrate the ongoing process of invention. They show how close attention to objects can confuse scientific objectivity, and, in the end, they replace scientific exploration with a dedication to pure, creative vision. 19 In "Marion Bard"-just like the subsequent "In the Labyrinth", we see the strong subjectivity of the seemingly calm approach, especially when one idea creates another, the plot develops The way. Like a prelude, the opening shots show the subject to be developed. As "Marion Bard" unfolds, the image separated by the camera earlier-as it gradually moves to the hotel theater-becomes more and more important. The opening drama projected a concentrated image of events, style and background-these elements will be gathered in the story of A and X. When the curtain falls, the audience of the play becomes a potential carrier of the plot. The camera scans the audience, and different couples clearly express dialogue fragments-this will soon become the field of A and X. We have witnessed the constant search for the protagonist to the formulation of the unfolding plot. This search is full of strong suspense. This tension is reminiscent of Cassavetes’ early improvisation films (especially "Shadow", 1959) and Pirandello’s "Six Searching Plays". The Role of the Writer (1922). This is the strain of imagination engaged in the activity of invention—almost ecstasy.

A and X are only gradually becoming the protagonists of "Marianbad", even so, the endless arrangement of potential materials continues. Different versions proliferate and produce additional variants, and the effort to shape the imagination of these materials becomes more and more obvious. When two recordings need to be merged into one in the initial audio track, or when the sound effect needs to match the picture, occasionally, X’s description of the event and the picture accompanying its description need to match in order to produce the coherence of these events (even if Not the real) version. When these materials are changed to be consistent with each other, "Marianbad" records the deliberate effort required for such adjustments. Therefore, when X describes the past segment, suppose A is leaning on the railing and "the sound has stopped." A is not in the position indicated by the read aloud... Then she corrected her position... As soon as she changed her position, X's voice continued immediately, as if it was only waiting for this action" ("Marian Budd," Page 62). On another occasion, X talked about a past event, which was not recorded in video. The complementary picture shows A now listening to his narration, but when she laughed, X said, “Then You start to laugh" and use the current events to confirm his "report" of the past (Marianbad, p. 52). Both events involve the separation between images and narratives, but they differ in The method uses this separation. The laughter reflects X’s need for verification; he adjusted his narrative, using A’s current behavior to prove the accuracy of his memory. In contrast, the section where A is leaning against the railing Shows X's control over visual materials.

Efforts to align the picture and the narrative are repeated repeatedly in "Marianbad", establishing Robbe-Grillet's focus on evidence and validity. For example, X's claim to be intimate with A depends in part on whether there is a mirror or snow scene on the mantelpiece in Room A. This work records these two options, gives them equal validity, and, importantly, the same picture [frame]. Before the mirror reappeared in A's room, the film made it appear in the living room of the hotel several times, thus invalidating these two options. One can draw the conclusion that "Marianbad" implicitly assumes that anything imaginable exists, whether it is seen, remembered or invented. However, even this comforting system proved to be unreliable. In X's so-called visit to A's bedroom, both A and the visual images refused to add to his narrative, despite his desperate control of them (Marion Bud, p. 125); later, X denied that a just emerged This version implies that he raped A (Marianbad, p. 147). To some extent, the relative autonomy of images and narration comes from the different viewpoints that govern each set of shots. 20 Sometimes, A's will prevails, and X's narrative has to back down. Sometimes, X's will prevail and shape the material. The image itself becomes a form of dialogue. They reproduce the theme of [re-enact] persuasion, relying on a belief that insights depend on one's will and imagination, rather than the stimuli encountered.

However, the viewpoints of X and A only partially explain the separation between image and sound. The opening and closing music of "Marion Bard" is still independent of the protagonist's point of view, as are all other sounds that are out of sync. The overture is "a romantic, passionate, and intense unison, which is used at the end of a movie with a strong emotional climax" ("Marion Bard", p. 17). Finally, when "it raises the volume and dominates" [original: "Afterwards the music rises and prevails", the Chinese translation is translated: "there is only loud music in the end" according to the Chinese translation], this kind of music is re-established Its autonomy (Marianbad, p. 165). In its focus on humanity and clichés, this music satirically commented on the surging emotions it expresses. This irony, of course, is the author's, but because Robbe-Grillet immerses us in the perspective of his protagonist, the irony seems to be attributed to the music's own judgment. Similarly, the camera's early processing of the cast and crew dramatized its transformation from being full of artificial traces to lifelike. When the work is over, the last scene shown by the camera is zoomed away from the moonlit front of the hotel. Robbe-Grillet clearly gave the camera the autonomy of expression:

The camera is close to the young men and women, and their voices are reduced (not increased). The young men and women entered the close-up close-up shot, but it was not shaped because the camera passed through them, as if they had deliberately avoided the camera, and their voices disappeared completely. After the couple disappeared, the camera lens stopped at the place where they had just been blocked. ["Marianbad", p. 38]

Robbe-Grillet's language obscures the fact that the camera is a tool controlled by himself, Renai and the photography team. The movie version matches the text very well. It makes cameras and recorders appear obtrusive, and gives them autonomy, intelligence, and selectivity. This camera is a never-ending, exploratory camera. It approaches or sets aside the characters with extremely independent independence.

Anyone familiar with the "Marion Bard" movie will think of "white scenes" ["white scenes"], especially as an example of the positive role of the camera. As Morissette said, the camera gradually became dominant; it seemed to have reached such a strong emotion that the quality of the film was affected. However, the "white scene" did not appear in the text. This film reinforces the lens activity pointed out by Robbe-Grillet, and its new material goes beyond the original intent of the text. By treating the camera as an intoxicating [ecstatic] character, the film thus crosses the watershed between doubt and faith. Although the repetition and changes of the bedroom scene fragments still reflect the focus on authenticity, the light and rhythm dominate the audience's experience. The camera reproduced the theme of rape and lover combination. It penetrates A's room with an accelerated, pulsating movement, and the film becomes overexposed, as if responding to the passion it records. The scene itself is like a strong orgasm metaphor. It succumbed to an unreasonable ecstasy that made considerations of authenticity seem trivial and digressive. It rejects the "scientific" investigation of facts. Instead, it celebrates the energy of creation, which produces a series of visionary words.

V

Some moving hypotheses allow certain artists to connect their art with science. The theories of Zola’s “experimental” novels, such as Durrell’s adaptation of Einstein’s theory of relativity, or Robbe-Grillet’s efforts to reconstruct the apparent neutrality of scientific observations in the novel, are all self-verifications. -validation] effort. They stem from a lingering uncertainty about the value of literature. In a world where science is considered the door to happiness, artists often feel pressured to prove that their work is useful and therefore progressive. In "Nature, Humanism, Tragedy" ("New Fiction", pp. 49-75), Robbe-Griller makes a very clear connection between progress and science. This connection makes him try to make his art Close to science. But Robbe-Grillet is clearly not close to science. In his novels and movies, passionate material and seemingly neutral positions are intertwined to form a contradictory combination. The "white scenes" that Renegaard added to Mariambad illustrate this paradox because they contrast with Robbe-Grillet's intentions. While Renai clearly praised the subjective vision, Robbe-Grillet is still committed to his seemingly calm approach and disturbing melancholy, which is the consistent characteristic of Mariambad. Rob Grillet has never been on the side of invention like Renai. He has never resolved the conflict between his desire for objective knowledge and the subjective and doubtful inevitability.

In view of Robbe-Griller's dedication to a calm narrative mode, the uncontrollable nature of irrationality is very prominent in his works, although it is not as obvious as Reynold's version. "Marianbad" communicates through a network of referential symbols full of emotional content. Robbe-Grillet's metaphorical functions are similar to Eliot's "objective counterparts": they communicate through juxtaposition. 21 They are equivalent statements, and specific things become signs of specific emotions. Therefore, what A breaks is equivalent to her deviant. The decoration of the hotel symbolizes the inner turmoil of the guests. The mirror and ambiguous lights correspond to the epistemological mystery in this work. The structure of Mariambad itself has a metaphorical function. Neither the text nor the film sorted out its plot. Neither provides clues about what is real, what is remembered, and what is imagined. The past, the present, and the fantasy become indistinguishable, and the two words "true" and "false" lose their meaning. It is easy to interpret this dislocation of time sequence and real concepts as another maze, which implies that the audience directly seeks coherence and escape. This interpretation applies the traditional usage of metaphor to the overall structure of the work. It creates another correspondence, this time between form and content: the work focuses on the traps in the labyrinth, and the form dramatizes it.

It is not inaccurate to view the structure of "Marianbad" as a formal representation of its content, but it is too limited. Robbe-Grillet establishes a correspondence between form and content in all of his works. He always uses labyrinths—physical or spiritual—to express entrapment and exploration. However, it is useful to identify Robbe-Grillet’s preferences, mainly because they shed light on the new material that emerges from apposition—composite. The important fact is that by eliminating the accuracy of time, Robbe-Grillet also eliminates the concept of causality. One cannot rearrange the fragments of Mariambad into a recognizable coherent narrative of human experience. Clothing, background, time and place of events are all changeable. For example, A’s snapshot seems to record a past event first; when it becomes an animated scene, people can still use it as a dramatic memory of that event, except for the subsequent snapshots with an unexplainable amount of The copy reappears in A's bedroom. This set of shots is surprising because it separates the snapshot from its intended use of evidence without providing another explanation.

Robbe-Grillet refuses to provide the comfort of traditional order and continuity. To appreciate "Marion Bard", you must overcome the old habits of reading and watching movies, and accept the fact that it is futile to find a traditional plot. Anyone who has been trained in traditional narrative art will find it difficult to accept "Marianbad" as it should be. To make matters worse, Robbe-Grillet himself has set up barriers to this acceptance. He described the work as “a story of persuasion” (M, p. 10), and the series of plots he provided did unfold like a persuasion: the opening drama heralded the ending, X’s courtship gathered enthusiasm, and finally A and X seem to be leaving the hotel. Despite the false start in this dead end, this series of plots is still eye-catching and acts as a decoy. It uses the linear development demand bred by tradition to induce us to engage in the frustrating chore of plotting to maintain a fictitious time sequence. However, "Marian Bud" dispelled this effort. Its elusive model cannot be rationalized into "memory" or "fantasy." First of all, how do we deal with the distortion of the shots of the snapshots and other similar plots? How do we understand the fact that works start in the present tense but end in the past tense? twenty two

The transition from the present to the past happened unknowingly. The dialogue, naturally, remains in the present and maintains the immediacy of the action, but X’s monologue (“again—I’m going forward...”) was transformed into the past tense very early and was mistaken for a The so-called "last year" nostalgic conversation. As the authenticity of such memories becomes more and more suspicious, the audience is likely to reclassify some of X's narration as fantasy. This effort to rationalize information is natural, except when the work is drawing to a close, it puts the audience in an untenable position. A and X appeared in their travel costumes, apparently about to leave. The next shot—the last one—shows the front of the hotel in the night receding [sic, but the last scene in the film only shows the night In the front of the hotel, the camera does not move back]. When these visual materials signaled withdrawal, X's voice told a somewhat different story:

The large garden of this hotel is a French-style garden. There are no trees, no flowers, and no plants. Gravel, stone, marble, and straight lines make the space rigid and make the appearance without mystery. At first glance, it doesn’t seem to be You may get lost here...Along the straight path, between the deadly statue and the granite slab...At first contact, it seems that you won’t get lost...and now you are getting lost, alone in this quiet night. Follow me forever lost direction. ["Marianbad", p. 140]

"Marianbad" ends with these words. Obviously, this ending does not mean simply leaving and moving towards a more free life. There is indeed a mystery on the surface, and claustrophobia still exists. "Marianbad" is not the small town of Marianski [Marianské Lazne, the second largest spa town in the Czech Republic]. The idea of X and A starting a new life together in Brussels or Lyon is, at best, absurd. X's final monologue described a past event-A was lost forever, with X, in the dark. This passage is obviously ambiguous. Although it recognizes the combination of A and X, and suggests that being lost may mean being found (just like death in Ibsen's "Rosmore Manor" means some kind of freedom), the ending is still ambiguous. The past and the present form a circular continuum similar to the Mobius ring. The audience must either deceive themselves, ignore the changes in the present tense and the meaning of the last sentence of X, or give up the need for traditional narratives.

"Marianbad" is a private labyrinth for the audience because it uses our habitual response to the narrative to lure us into a continuous, hopeless struggle to rationalize the material. Robbe-Grillet's "introduction" is not a golden thread. It arouses our attention to the conceptual labyrinth he has established, but it does not reveal his overall expectations or the nature of persuasion that he considers to be the core of the work:

As long as a brief overview of the script, it is not difficult to see that it is impossible to make movies with traditional forms of such subjects. What I mean is to use a straightforward approach to “logically” link the scenes, because the content of the entire movie is A process of determining confidence: the master shares his own imagination and creates a reality in his own language. His stubbornness and confidence in his heart finally made him triumph because of how many detours he has gone through, how many twists and turns he has encountered, how many failures he has suffered, and how many rounds he has gone through! ["Marianbad", p. 15]

Despite this statement, it is not certain whether X has the advantage. His last monologue is an elegy, not a victory, and there is only one sentence that separates it from the end of the work: "Then there is only loud music" (Marian Bud, p. 140). 23 At the end, like the whole work, it resists the effort of rationalization. People can try to suppress unwelcome contradictions, but this method is not satisfying. It implies that the audience seeks practical solutions, blurring the macro vision of the work. In order to accept this vision, readers and viewers must abandon the pursuit of traditional meaning. They must abandon the maze, not just seek to leave. Only by recognizing the ambiguity of this work and willing to maintain-rather than suspend-doubt, can the audience fully experience it. Robbe-Grillet's art mainly relies on the internal process of producing a series of visual and auditory signifiers. The audience's task is to convert signifiers into recognizable meanings and to combine these signifier strings into a coherent whole. The positive role of the audience does not mean that the continuity that emerges in the film comes only from subjective projection. As we have seen, Robbe-Grillet paints its clues and controls it through familiar symbols and a focus on archetypes. Gathering and accumulation are the core of his communication and rely on the participation of the guided audience. Like any narrative, "Marianbad" unfolds in sequence. However, although the traditional narrative relies on the viewer's memory to produce a linear understanding of the causal sequence, the meaning cluster here mainly exists as an exploration of alternative versions. Robbe-Grillet relies on the viewer's memory to preserve the evolving visual overlap. The experience of the whole work is polyphonic. A cumulative knowledge emerges through the arrangement of the screens.

Just like in music or architectural works, the fragments of "Marianbad" derive meaning from the series of schemas they form, and from the effectiveness of their discrete symbols. The work relies on the connection between its parts, on the repetition, juxtaposition and change it depicts. The metaphorical materials echo each other, complement each other, are intertwined and stand out, and are gathered and repeated in the overall structure of the work. The constitutive attention to location, rhythm, and time period is so obvious that it almost replaces the representational interest that the work may have. The struggle to transcend entrapment and death runs through the emotional content of the work, and the traditional use of metaphor in "Marian Bard" attracts the audience to share the experience of the protagonist with empathy. At the same time, the broken work attracts the audience's rationality and imagination, and invites them to appreciate the complexity of the unfolding design, as if it is an abstract creation in itself. For example, the stimulus of juxtaposition depends only in part on the materials being juxtaposed; the choice of material is important, but the way and duration of their presentation defines meaning and produces a relatively independent consideration of the subject—it was originally The basis of choice-the aesthetic experience. The interest here is largely rhythmic and structured, and it relies on a close system of reciprocal relationships.

Since the film-fiction and film versions of "Marion Bard" are both narratives, their internal interrelationships can only develop over time. Although these two media reach their audiences in different ways, the charm of any version of this work depends to a large extent on the gradual evolution of narrative choices. "Marion Bard" is never static. Its lens illustrates the previous material or provides a contrast between them. It entices its audience to become the author's intimate complicity in thinking about the creation of the novel. 24 In the sense of Joseph Frank's "spatial form", "Marion Bard" is not "spatial". 25 The dismantled time, the truncated events, and the inconsistent narrative did not turn it into a spatial combination of narrative fragments that coexist on a plane that readers and viewers can grasp immediately. It takes an hour and a half to watch this movie, or several hours to read its text, which is an unavoidable fact. Spatial and visual analogies like Frank distorted the nature of time in these two media. "Marianbad" is neither symbolic nor static. Words like pattern, system, design, or combination do not necessarily describe interrelationships. The elimination of "plot" (according to EM Foster's understanding, "the king died, and then the queen died of grief") does not mean that synchronicity (Frank's "spatial form") has replaced temporality. In "Marion Bard", like in "Ulysses", "America", "Under the Volcano", "The Sound and the Fury", "Pale Fire" [ Pale Fire ], "The Bluest Eye" and many other modernisms As in postmodernist works, the elimination of a certain type of sequence [sequence] will only bring another type of sequence.

The above analysis of "Marianbad" emphasizes the inevitable diachronic nature of all narratives, and therefore challenges the concept of "spatial form". The deconstructive vision of modernism and postmodernism denies the order of time, but it cannot transcend the timeliness of expression and acceptance. Early research on film montage helps them focus on the temporality of non-historical sequences. The "Kuleshov effect" ["Kuleshov effect"] shows that, for example, when an actor's expressionless face is followed by an empty plate, the audience thinks that face expresses hunger. The perception of different images seen in succession is a three-step process, that is, receiving material and assimilating it into a coherent (even if not decisive) representation. "In order to achieve its effect, a piece of art guides all the means it has to deal with," wrote Sergey Eisenstein. "A work of art, to be dynamically understood, is a process of arranging images in the audience's feelings and consciousness." 26 The point is that the nature of narration must be continuous and dynamic. Similar features and interconnected sound and image networks have always been used as a sorting and communication tool in literature and film. The recent deconstruction of art has emphasized the importance of non-chronological but continuous patterns. Elimination of one kind of reasoning that historical causality (a long-term famine caused them to invade the neighbor’s land; or, the king died, and then the queen died of grief) does not mean that other types of reasoning were abolished. 27 Deconstruction means reconstruction, and at least in novels and movies, this reconstruction continues to depend on continuity [succession]. "Marion Bard" cannot free itself from this sequence. Its temporality forces people to participate in the ongoing invention process. This situation, similarly, reveals Robbe-Grillet's view of the real world. 28

Thinking of "Marion Bard" from the perspective of structure, rhythm, and unfolding design may suggest that it approximates an abstract narrative. This view fits Robbe-Grillet's approach and style. The precision of control in his writing and his talent for developing and juxtaposed narrative sequences are so compelling that they cause people to pay attention to themselves, at least as much as to the human situation they portray. His intuitive discoveries [intuitive dis

View more about Last Year at Marienbad reviews