Antonioni is particularly good at the end of the movie. At the end of "Eclipse", Montage feels the emptiness of the entire city. The texture of the urban architecture is infinitely magnified, but the two lovers cannot arrive as expected. In "Magnification", Hemmings finally picked up the emptiness. Tennis, throw it into the air; in "The Traveler", the super long magic lens slowly moved out of Jack Nicholson's room, through the window to the abandoned square, and then slowly returned to the room. Within, Nicholson was found dead on the bed.

I watched all these movies at least a year ago. But all these images have left an indelible impression in my mind, lingering like a nightmare, and I believe that everyone who has watched these movies will feel this way. This proves to what extent Antonioni is a visual director-this not only means building a story with vision, but also means his fascination with the visible, and even the fatal fascination with the invisible. Antonioni is obsessed with "the surface of things." Antonioni shows us the world—sometimes, it is a "natural" world, but more often, it is an artificial world—but he shows the world in a way that we have never seen before. : What he showed us is a world that is a visual image, a world that has shrunk into a visual image, a world that has become a visual image. This is why we feel dizzy when watching Antonioni's movies. Because all the things we see are not objective presentations, those things are always reflected and affected, they are always the projections of characters' claustrophobic minds, their counterparts of narcissism, neuroticism, loneliness, and nausea; however, At the same time, everything we see is completely separated from the subjective feelings of the characters, as if the camera came quietly from the outer space, and to it, the characters' behavior is as absurd as we see the behavior of flies. Bizarre. Antonioni’s film is a combination of the two. One is excessive subjectivity, which seems to draw us into the territory of death, and the other is the too dehumanizing distance, which creates barriers to understanding and interpretation. , And the combination of the two created Antonioni’s poetic style.

Antonioni's movies are also about time. How time passes, and how it feels to wait and continue. As Bergson said, in order to melt the sugar, you have to wait. It will not melt in an instant. Antonioni's film is an allegory of waiting: waiting can be as fast as sugar melts, or as slow as death comes. Antonioni captures this kind of waiting, and like Proust, he regards the passage of time as the essence of human internality: he captures the pain of waiting and the joy of waiting, and no director can beat him.

Antonioni is also a poet of the body. As Deleuze said, Antonioni's film is about "infinite fatigue of the body" and "the attitude and posture of the body." For Antonioni, what remains on these body attitudes and postures is no longer experience, but a remnant of past experience, that is, after all that I want to say has been said, and all that I want to do has been done, what remains is Those residues. What he showed us was what was left after everything was gone, and what was there when everything hadn’t started: and all these remnants were engraved on the body, this These are unconscious bodies, and the mind does not lead there. Antonioni is a poet of the body, which means that he uses his vision to tell us the things that cannot be said, those things that the body can feel but cannot express.

Antonioni is a modernist poet. Of course, for modernism, it is already a cliché to combine those strangely beautiful things with hidden despair. But what is special about Antonioni is that he allows his characters to be absorbed by those landscapes irresistibly, and changes them and reflects them: those beautiful and terrifying landscapes not only express them, but also absorb them and chew them. Against them. Antonioni always deals with the relationship between people and the environment in which they live.

Then, what about the political leanings of Antonioni's films? The first trilogy told the story of the wealthy bourgeoisie. All the characters are not upset about the economy. Their confusion lies in their personal loneliness and the shackles of being unable to communicate with others—of course, they also have the ability to be unable to obtain happiness. , Even without desire. More often, these characters are women, and Antonioni looked at them with pity, although at the same time, he could not help but objectify them as sexual goals.

Leftist criticism of Antonioni always says that he beautifies the decadent life of the bourgeoisie. But again, this criticism is superficial. Antonioni criticized class relations and gender relations, but he never moralized this criticism, for example, like neorealism, portraying proletarian life as a substitute for the bourgeoisie. Antonioni’s films always have a numb feeling. Its characters are numb, and it inevitably numbs the viewer. And this feeling of numbness is the inevitable feeling after class differentiation and sexism in capitalist society have developed to the extreme. The character's neuroticism, narcissism, and lack of emotion are all "subjective" results caused by "objective" capital appreciation.

In "Red Desert", Antonioni left us with the most memorable color shot in film history. These evil colors can't go away like ghosts. They are the footnotes of a fable: Monica Vitti told her son that there used to be a paradise beach: there, the color and light are so clear and clear, everywhere. Billboards flooded the corners. This is an ideal that the bourgeoisie cannot realize: Antonioni tells us that this is just the opposite of the lingering industrial ruined society in the movie. Antonioni's poetics is the poetics of waste and rubbish.

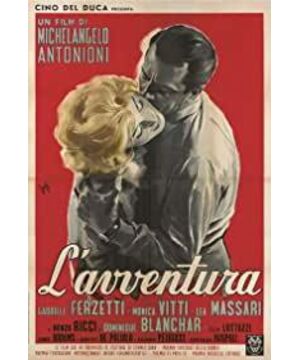

View more about L'Avventura reviews