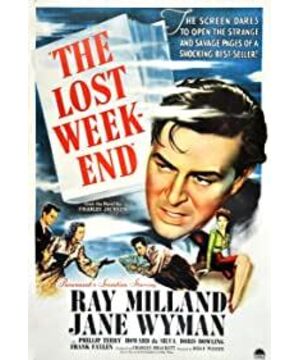

Having apprehended the précis of what the film is about, one's knee-jerking question might be, what is the allure of watching a congenital soak drinking himself to stupor over a weekend's spell if the viewer is fortunate enough not being subjugated under such a distasteful spell ? SurelyBilly Wilder's THE LOST WEEKEND, a prestigious Hollywood classic and Oscar's BEST PICTURE winner, can dissipate this nagging doubt, because alcoholism is just one of many a jones scourging our human race, more or less, everyone can find some connection with the story, and Wilder sensibly attest that the battle cannot be won without the cooperation ofown's volition and the external succor.

Ray Millard plays a New York writer Don Birnam, driven by his execrable addiction to the brink of self-destruction, and Mr. Millard's Oscar-winning performance is a tour-de-force with a capital T. It is a daunting task a priori , Don is not necessarily a character who can rally audience's compassion prima facie, a coward he is, indeed, shirking from a resolution of fighting back, apparently he doesn't deserve redemption, not least a virtuous girlfriend like Helen St. James (a saintly Wyman), who has been nothing but supportive for three years by his side. Don's ordeal is a vicious circle which he has no strength to shuck off, Mr. Millard viscerally points up his painful struggle, poignant self-pity, undignified resignation ( when he deigns to pilferage, scrounge and coercion on multiple occasions to slake his craving),plus a vestigial ghost of hope through theutter misery shrouding Don's downward spiral.

Maybe we shouldn't root for Don after all? It is not hard to conjecture Mr. Wilder's would stick to his gun until the finale (as in his pièce-de-résistence ACE IN THE HOLE 1951), since Don's ominous undoing is primed like such an inexorable force rushing in the homestretch, to a certain point, it even seems audience would be okay with a totally tragic denouement in this cautionary tale, which actually makes the far tooconvenient magic cure near the finish-line feel contrived and compromised, a quibble might be deemed as a blemish on the film's otherwise intact integrity, again, it is not the happy ending per say which rouses one's demur, but is the wholesome process how that ending is presented. In this case, it is unsatisfactory by half .

Visuals-wise, Wilder tactfully interlaces some expressionist panache onto the movie's monochromatic sheen, the most striking specimen is the moment when Don is temporarily locked up inside a drunk ward (where Frank Faylen makes an impressive cameo as a male nurse), the horror and despair does creep against the shadows of iron bars and its aural cacophony into a spectator's core, not to mention the bat-assaulting-rat figment in Don's delirium later, burnished by Miklós Rózsa's nightmarish and eerie string score, which, sometimes, is truly unsettling as our sonic cues of inner-anguish and self-abandonment.

There is irony too, the “Champagne Aria” from LA TRAVIATA which tantalizes Don's thirst is a hoot, so is Don's desperate attempt to hock his typewriter on the day of Yom Kippur, for all its intents and purposes, THE LOST WEEKEND is a transfixing social critique in its essence, but laden with some less savory footnotes, for instance, that game-changing kiss sweeping Gloria (Dowling) off her feet is so damn an exemplar of male wish-fulfillment, Wilder and his screenwriterCharles Brackett should've known better, no well-adjusted woman could enjoy a moribund man's booze-macerated kiss, not even it is from someone who is as good-looking as Mr. Millard, that is what this reviewer can vouch for.

referential points: Wilder's ACE IN THE HOLE (1951, 9.0/10), DOUBLE INDEMNITY (1944, 8.2/10); Mike Figgis' LEAVING LAS VEGAS (1995, 7.7/10).

View more about The Lost Weekend reviews