by Aimée

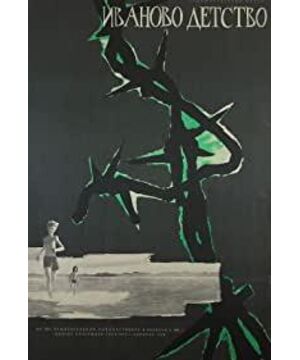

In Ivan's Childhood (1962), Tarkovsky incorporates four dream sequences into a war narrative of a twelve-year old Soviet solider Ivan whose childhood is brutally shattered by the war. While the reality of war produces only fear and horror, an oneiric space in contrast offers an alternative universe of comfort and joy. After the Nazi massacres Ivan's mother, his life becomes filled up with pain and rage. Determined to avenge, Ivan refuses to attend military school and insists on fighting on the front line, which ultimately leads to his murder by the Nazi. In my paper, I will focus on the opening and ending dream sequences. I would argue that these two sequences visually materialize a blissful childhood that Ivan can reside in on the screen but could never have lived. Furthermore,Tarkovsky's revelation of world through poetic and oneiric imagery thus accentuates a visual counterpoint to a bleak and harsh post-war reality of pain and loss, offering consolation to Ivan and the viewer. However, while affirming the cathartic and healing power of cinematic imagery, Tarkovsky articulates the instability of the oneiric space and refuses to render fictional resolution on the screen.

Stylistically differentiated from the rest of narrative, the two dream sequences present a warm, dynamic world that offers Ivan security and joy. The stylistic difference is characterized by changes in the choice of lighting and in the rhythm of camera movement. By using natural lighting instead of staged chiaroscuro lighting and freely moving hand-held camera instead static framing, Tarkovsky effectively presents the viewer with a dynamic world full of lively, luminous imagery different from the harsh, disenchanted reality of war. As the camera pans up the torso of a thin tall tree marked by its femininity and tenderness, the viewer is elevated from the ground to the top of the tree. In an extreme long shot, the viewer finds Ivan standing in the meadow and bathed in sunshine. As Ivan turns around and looks back in the direction toward the viewer,a world of affectionate and luminous imagery unfolds on the screen before the eyes of the viewer. The camera swiftly cuts to a close-up of the animated face of a goat staring at the camera, as if the goat has returned Ivan's gaze. Here, the consolation is primarily enabled by the act of looking. The viewer is directed to look closely at the physiognomy of animals and patterns of things to form a meaningful connection with nature. The hand-held, wiggling camera also leads the viewer to visually track the movement of a butterfly in an experience of liberation. Nature not only surrounds and embraces Ivan; it also protects Ivan and provides him with happiness. In this alternative oneiric space, Ivan regains a blissful childhood that he could never have lived during the war.

Intriguingly, the point of view that many of these shots provide is ambiguous: the viewer is unsure through whose perspective he or she is seeing. The ambiguity is exemplified by a disorientating panning shot of earth followed by Ivan's flight. The fast-moving camera pans from left to right at decreasing speed, as if the camera is trying to position itself after the exhilarating flight. It may naturally follow that in this shot one gains access to seeing things by identifying with Ivan. However, as camera pans further to the right , the viewer discovers Ivan standing by the side of the earthy surface and curiously listening to the sounds of nature. The images thus suggest that there is someone or something else that is also looking at the lively, beautiful things. It is implicated that,in a more ambiguous way than that in the shot where a goat stares back, nature may be returning the gaze of Ivan and the viewer. In the exchange of gazes that precipitate an increasing degree of appreciation for beauty, the orphan is able to immerse himself in the luminous world of joy and alleviates the painful experiences of solitude and loss. The viewer, who is also engaged in the act of looking, is offered such consolation as well. The extended image of the thick earth and residuals of aged tree branches also grounds Ivan as well as the entire film in the comforting natural world that distances itself from the world of human-inflicted atrocities and pains.the orphan is able to immerse himself in the luminous world of joy and alleviates the painful experiences of solitude and loss. The viewer, who is also engaged in the act of looking, is offered such consolation as well. The extended image of the thick earth and residuals of aged tree branches also grounds Ivan as well as the entire film in the comforting natural world that distances itself from the world of human-inflicted atrocities and pains.the orphan is able to immerse himself in the luminous world of joy and alleviates the painful experiences of solitude and loss. The viewer, who is also engaged in the act of looking, is offered such consolation as well. The extended image of the thick earth and residuals of aged tree branches also grounds Ivan as well as the entire film in the comforting natural world that distances itself from the world of human-inflicted atrocities and pains.The extended image of the thick earth and residuals of aged tree branches also grounds Ivan as well as the entire film in the comforting natural world that distances itself from the world of human-inflicted atrocities and pains.The extended image of the thick earth and residuals of aged tree branches also grounds Ivan as well as the entire film in the comforting natural world that distances itself from the world of human-inflicted atrocities and pains.

Taking his cinematic mission even further, in the ending sequence, Tarkovsky offers the viewer a deeply tactile, consoling experience that goes beyond the visual and aural engagement. The viscous exchange between the film and its viewer gets to beneath the skin and reinvigorates the body. Tarkovsky locates the majority of his images in an unkind nocturnal space: the expressionist mise-en-scène that persists throughout the war narrative is as psychologically unsettling as the reoccurring harsh sounds of diegetic gunshots. The oneiric space, in contrast, is saturated with sunlight spilling over the imagery. After a series of unnerving war images is delivered to the viewer in a mixture of fiction and documentary footage,the viewer exists the ghostly and spine-chilling Nazi office where Ivan is brutally murdered and immediately enters the dream world that is illuminated by exuberant amount of natural light. In a long tracking shot reminiscent of the ending of Truffaut's 400 Blows, Tarkovsky's dynamic hand- held camera adds invigorating energy to Ivan's running and alleviates the melancholy caused by Ivan's longing for freedom and happiness. In a long shot, Ivan runs away from the shore toward the sea as the splashing waves spread out around his feet. The viewer, as if are invited by the shining sea waves, can almost feel the warmth of sun and water as Ivan does beneath his or her skin. The tactile camera eye thus affirms the cathartic power of images.These shining images in contrast to the gloomy images of war and death offer solace to Ivan as well as to those who may have had the experience of loss during the war and to those who have not had direct war experience but are nevertheless affected. In effect , Tarkovsky's camera transfigures a bleak reality into a luminous world.

However, it is important to note that Tarkovsky rejects the escapist approach to post-war filmmaking that is evident in post-war pictures such as German Heimat films. While affirming cinema's healing power, he nevertheless casts doubt on the stability of the perfectly constructed cinematic space and denies the pleasure of fictional resolution. Ivan's Childhood does not promote pure escapism or supply propaganda to gloss over the war. Often times, the serenity of the alternative cinematic space is mercilessly disrupted by the sound of gunshots, as the gunshot recurs and repeatedly murders Ivan's mother in his dreams. In one of most serene moments of the film, Ivan regains a lighthearted childhood after his death and plays with his friends on the sand by the sea in sunlight. However, in the game that Ivan is playing,after Ivan points at his friends who form a circle around him, the friends consecutively fall down as if they are shot by an invisible gun. As the bodies of Ivan's friends collapse down and encircle him, the bodies become stand-ins for Ivan's deceased families and friends who are visually absent. The circle of bodies also metaphorically cast a web of death over Ivan, which resonates with the spider web that blocks Ivan's face in the opening dream sequence. Thus, the oneiric and luminous space is nevertheless permeable to external dangers and potentially unsustainable.The circle of bodies also metaphorically cast a web of death over Ivan, which resonates with the spider web that blocks Ivan's face in the opening dream sequence. Thus, the oneiric and luminous space is nevertheless permeable to external dangers and potentially unsustainable.The circle of bodies also metaphorically cast a web of death over Ivan, which resonates with the spider web that blocks Ivan's face in the opening dream sequence. Thus, the oneiric and luminous space is nevertheless permeable to external dangers and potentially unsustainable.

Despite that the indelibly beautiful cinematic space has the power of catharsis, whether this oneiric world is ultimately untenable remains ambiguous. While Tarkovsky wholeheartedly affirms the healing power of poetic abuse images, he refuses to this power. In fact, the flight that Ivan takes substantiates potential peril lurking behind the shining oneiric world and evidences Tarkovsky's discretion. While Ivan enjoys the blissful freedom of flying, the camera that accelerates in its downward movement foreshadows a potential pitfall and impeding death upon hitting the ground of reality. Tarkovsky's cinema is thus a realm of ambivalence that exists in a liminal space between dream and reality.The descendent flight that Ivan takes would be explicated four years later in the opening sequence of Andrei Rublev where the peasant-inventor Yefim's exhilarated flight is cut short when he violently crashes into the ground. After the camera accentuates his tragic death in a freeze-frame shot, however, Yefim is cinematically resurrected in the subsequent images where a sprawling horse gets up and trots off in free spirit.

View more about Ivan's Childhood reviews