Author: Sartre Article Source: Literature Hits: 297 Update Time: 2006-11-1

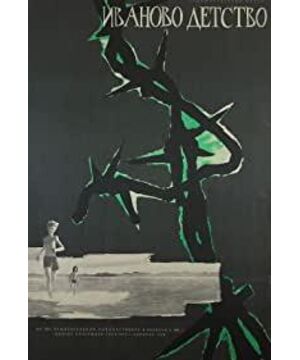

Background: In 1962, Tarkovsky's debut novel "Ivan's Childhood" was obtained in Venice Won the Golden Lion Award and sparked controversy in the critics. Sartre, who was living in Italy at the time, wrote this letter to Alika, the editor of Unidad, and talked about his own views on the film.

Hello, Alicat:

On many occasions, I have expressed my sincere respect to you more than once for the work done by critics of your newspaper in literature, sculpture and film (fields). I found (in their comments) that rigor and freedom go hand in hand, and this means that while grasping the uniqueness of a work of art, they can also hit the point of the problem. Perhaps, I want to repeat Paisa. Serra's praise: There are no leftists who follow the dogma, and there are no leftists who have rigid thinking.

And this is why I want to complain to you today. "Ivan’s Childhood" is one of the most outstanding movies I have seen in recent years, and the evaluation of this film by "Unity" and other left-wing newspapers gave me the first impression that this is not just a follow-up. , Is it a pattern of blame? The jury gave the film the Golden Lion, which represents the highest honor, but in the eyes of the Italian left, this proves strangely that the film is a product of "Westernization" and Tarkovsky is a director suspected of petty bourgeoisie. In fact, it is this inescapable conjecture that makes our middle class miss this profound and revolutionary Russian film that expresses the emotions of the younger generation of the Soviet Union in a typical way. Because at that time in Moscow, whether it was the first screening in a small area or the subsequent release, I watched this film with young people. I know what this movie means for these young people in their 20s. As the successors of the Russian Revolution, they never doubted this glory and are ready to carry it through: I can assure you that they are In the film's identification, there is not the slightest "petty bourgeoisie" reaction. Of course, this does not mean that critics have to accept all of the works of art they are evaluating, but is it appropriate for this film that was enthusiastically discussed in the Soviet Union to be so contemptuous? Regardless of these discussions and their profound significance, is it appropriate to criticize "Ivan's Childhood" as an example under the current Soviet system? Dear Alicat, I certainly know that you do not agree with the oversimplification of critics. While extending my sincere tribute to them, I hope you can let them understand the purpose of this letter, and perhaps make the content public before this discussion is too late.

These critics regard expressionism and symbolism as outdated and conservative. In my opinion, their formalistic framework itself has to be scrapped. Indeed, in Fellini and Antonioni, symbolism is cleverly disguised, but in fact the final effect is more obvious. Italian neorealism cannot avoid symbolism more. In fact, it is necessary to talk about the symbolic function of most realist works, but it is not suitable to expand because of space limitations. Critics accuse Tarkovsky of this characteristic of symbolism. They said that the symbols in the tower's works are expressionist and surrealist! And this is exactly what I cannot accept. First of all, here, like the Soviet Union, there is an academic accusation against the young director. Some critics there, just like yours, think that Tarkovsky has accepted some outdated Western art forms with a half-knowledge and used them uncritically. They accused him of Ivan’s dream scene in the film: "Look at those dreams! In our West, dreams are no longer needed to express! Tarkovsky is out of date, and this technique is just fine during World War II!" , Is the attribute of official critics.

Tarkovsky is 28 years old this year (this is what he told me, not 30 as written in some newspapers). It is certain that he lacks a sufficient understanding of Western films. The education he received must be Soviet in nature, and has nothing to do with the way the bourgeoisie handles films and related materials.

Ivan is crazy, a monster, and a little hero. In the real world, he is the most innocent and poorest victim of war. This child can't help but love, but has long been internalized and forged by violence. While the villagers were being slaughtered, the Nazis killed Ivan’s mother while also strangling him. However, he is alive. At that cruel moment, he witnessed the compatriots around him fall one after another. I myself have seen some young Algerians who often have hallucinations because they cannot bear the torture of the Holocaust. For them, there is no difference between a nightmare in a waking state and a nightmare in a night sleep. When they were killed, they wanted to get up and kill, and they became accustomed to slaughter. Their only courageous decision is to choose hatred and escape in the face of this uncomfortable suffering. They fight and escape this fear in battle. Once the night removes their guards, once they fall asleep, they regain the child's immaturity. At this time, fear reappears, and they regain the memories they want to forget. This is Ivan. I think it is necessary to thank Tarkovsky for showing so well, for this kid who is always ready to commit suicide, how the world is inseparable day and night. No matter what, he lives in another world. In this world, unlike ours, actions and illusions are very close. Please pay attention to this relationship, he stays with the adults: he lives in the army; those officers-brave people, brave but "normal", childhood without tragedy-protect him, love him, and use as much as possible He "normalized" and, in the end, sent him to school. Obviously, as written in Chekov's novel, the child can find one of the men to replace his lost father. It’s just that all this came too late: he no longer has the need for his parents to be with him; (than the loss of his parents), what’s more profound is that the hard-to-erasable fear brought about by the massacre made him fall into loneliness and isolation. . In the end, the officers decided that the boy was a mixture of meek, amazing, and painful distrust: they saw him as a monster, beautiful and disgusting, aroused by his enemies. It's just the urge to kill (say, a knife), and it cannot make a connection between war and death. Ivan now needs this ugly world to live, needs to escape from fear in battle, and needs to tremble to death in pain. This little victim knows what is inevitable: war (creating him), blood and hatred. However, the two officers loved him, and all he could do was not hate them. For him, love is a never-passing road. His nightmares and hallucinations are always inseparable from these three things. They have nothing to do with courage, nor to patrol the child’s "subjective world": they are completely objective, and we come from the outside. Looking at Ivan, it’s like those “realistic” scenes; the truth is that for this child, the whole world is a fantasy, while for others, the boy, the monster and the martyrs in this world are different. A kind of fantasy. Because of this, the scene at the beginning of the film cleverly introduced us to the child and the real and false worlds in the war, and described everything to us, from the actual process of Ivan’s journey through the woods to the false death of his mother (his mother) It is indeed dead, but that is a completely different situation, the meaning of which is so hidden that we can't know it). crazy? Reality? Both: In war, soldiers are crazy, and this monster-like child is the objective proof of their craziness, because he is the most crazy one. Therefore, what is involved here is not the question of expressionism or symbolism, but the specific narrative style required by this theme, just like the young poet Voznesensky said "socialist surrealism" .

To understand the exact meaning of the film's theme, it is necessary to dig deeper into the director's intention: even if it survives in the end, the war will kill those who make it. At the same time, there is a deeper meaning: in every movement, history needs (these) heroes, it creates them, and destroys them by making them suffer all the hardships in the society it has shaped.

While praising "L'Uomo da Bruciare" (L'Uomo da Bruciare, a 62-year film by the Taviani brothers, depicting a struggle between a syndicalist and a mafia), they reported to "Ivan’s Childhood." Take a look. They praised this debut work, praised its value, that is, it reintroduced the complexity of positive heroes. Indeed, the director gave the male protagonist some shortcomings-for example, exaggeration. At the same time, they showed that the sacrifice of this character actually stems from his self-centeredness and protection. But as far as I am concerned, I don't think there is anything new in this movie. Finally, outstanding socialist realism works always give us subtle and complex heroic images: they emphasize the shortcomings of heroes while also enhancing their strengths. In fact, the problem is not to measure the pros and cons of heroes, but to take heroism itself as the subject of discussion. Not to deny it, but to understand it. "Ivan's Childhood" points out the inevitability and ambiguity of this heroism. This boy is neither good nor evil, he is an extreme product created by history. He was thrown into this war involuntarily, and he was born for it. To say that he caused panic among the surrounding soldiers, it was only because he was no longer used to living peacefully. Violence originating from pain and fear stayed in him and took root. He survived on it, so he involuntarily accepted those dangerous reconnaissance missions. But what will happen to him after the war? Even if he survives, the hot magma in his body will not let him live. Here, in the most recent sense of the word, isn't it an important critique of positive heroes? He showed us that he was sad and noble; he showed us the source of the sadness and depression of his power; he revealed how the product of this war fits this militant society, and on the way to peace, he was Spurned by the latter. And this is how history makes people: it chooses them, tramples on them, and finally crushes them. Among those who are willing to fight for peace and sacrifice their lives, only this belligerent and crazy child fights for war. He lives purely for this, so he looks extremely lonely among the soldiers who love him.

However, he is a child. This lonely soul maintains the child's immaturity, but it is difficult to experience it again, let alone express it. Even if you return to it in a dream, or retreat from the daily hustle and bustle, these dreams are still inevitably turned into nightmares. Those scenes showing the end of the joy of the unborn child make us scared: we know this end. Although this immature is fragile and depressed, it lives in every moment of the present. With this immature, Tarkovsky carefully envelops Ivan: whether war, or even sometimes out of war, it is a world (I think of those wonderful scenes of fireballs across the sky). In fact, the poetry, the deliberate sky, the clear water, and the endless forest in this movie are Ivan’s ultimate life, the love and roots he lost, the appearance he once had, what he has forgotten, is Inside, surrounding him, others can see, but he himself no longer realizes. I know that nothing in this movie is more moving than this series of long scenes: the river is long, slow, and heartbroken; put aside their pain and doubts (is it appropriate to let a child risk these risks?) and stay with him. The officers were deeply moved by this terrible, lonely childishness; the boy was covered in dust and speechless: walking towards the enemy among the corpses in the wild; the boat returned from the other side of the river, and the water was silent: the prayer was short Withered; one soldier said to the other: "This dead silence is war..."

At that moment, this dead silence broke out: screams, anger, peace. In ecstasy, Soviet soldiers all over the consulates in Berlin: they ran and rushed up the stairs. One of the officers found a stack of rosters in a secret compartment; this was the style of the Third Reich: the names and photos of every hanged person are on the list. The young officer found a picture of Ivan, which read: 12 years old, hanged. In the national celebration of the pursuit of building socialism, there is such a black hole, which is as dazzling as a needle: a child dies in hatred and despair. Nothing, even future communism, can compensate for this. He showed us that nothing can bridge the gap between collective joy and this kind of individual, trivial suffering. At this time, not even a mother was hurt and proud of it. Human society is moving toward its goals, and the living will use their power to achieve these goals, but the small dead are like a humble straw that has been run over by history. It will always be a question mark, not providing answers, but like a new daylight that will illuminate everything: history is tragic. Hegel once said so, and so did Marx, and he also said that history often progresses through its dark side. But we usually don't want to say that in these recent times, we pursue progress and forget the things that we have lost and cannot be compensated. "Ivan's Childhood" reminds us of all this in a secret, gentle, yet very explosive way. A child died. Seeing that he could no longer live, it was almost a happy ending. I think, in a sense, what this young director wants to talk about is himself and his generation. It's not about the sacrifices of these proud and strong pioneers, but about their childhood and destiny shattered by war. The destruction of a child by his parents is a bourgeois tragicomedy. And tens of millions of children died or lived because of the war, which is a tragedy of the Soviets.

Therefore, this movie means a different kind of Russia to us. The technology is Russian, even though it is original. We Westerners know how to appreciate Godard's fast and simple to obscure rhythm, and Antonioni's natural and original slowness. But seeing these two styles appear at the same time in a director who has never been affected by this is really a novel experience. Tarkovsky used his unbearable slowness to bring people to the wartime years. At the same time, he quickly jumped from one period to another with a brief history (I especially think of the wonderful contrast between the two sets of scenes in the film: the river and the House of Parliament). During this period, the movie does not rely on the plot to promote the specific moments of the characters' lives, but reproduces them at another moment, or at the time of death. But from a social point of view, the feature of the film does not lie in the confrontation of these two rhythms. Those moments of despair are not many, but they are enough to destroy a person. We know that they appeared in this era (I can’t help but think of a Jewish boy in 1945, about the same age as Ivan, when he heard that his parents died in a Nazi gas chamber. When I was in the incinerator, I poured alcohol on the sheets, lay on the bed, lit, and burned myself alive). But we don't have the ability or opportunity to engage in a grand job. We know too well what evil is. At that moment, where good and evil confront, there is never extreme evil in good. This is what moved us: Naturally, the Soviets were not responsible for Ivan's death. The crime was the Nazis. But the question is not: Where does the evil come from? When evil pierces the good like a needle, it reveals the tragic facts of human and historical progress. Of course, there is no element of pessimism here, but it is not cheap optimism either. Some are just the will to fight and a clear understanding of its costs. Dear Alicat, I know you know this better than I do. Pain, sweat and blood are often the last thing people want to be included in the social price. I can be sure that you will appreciate this movie as much as I do for the lack of history of the dead. My respect to the critics of "Unity" also prompted me to ask you to let them read this letter. I would be very happy if some of the content of the letter gives them an opportunity to respond and revisit the discussion about Ivan. For Tarkovsky, the real commendation is not the Golden Lion Award, but the interest that the film can arouse discussion among those who oppose war and fight for freedom.

Just to all my friendship and respect

View more about Ivan's Childhood reviews