Almodóvar determined to establish positivity out of the melodrama's natural chaos by making the women exactly be “on the verge.

Author: Coconuttree666, a Chinese student who wants to be a serendipper in film studies and capture a kaleidoscope of colors in each frame

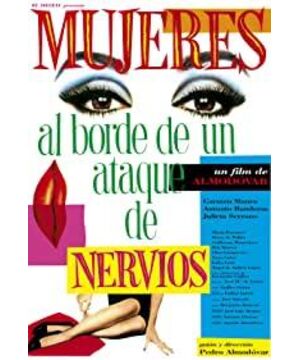

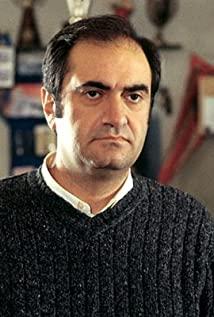

The 1988 movie Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown movie, directed by Pedro Almodóvar Caballero, is described in the academia as highly stylized with the “colorful characters, vertiginous plotlines and rich intergeneric allusions” (Acevedo-Muñoz, 2006, p. 173 ). Just as West (2013) stated, Almodóvar is among those filmmakers who insert personal experiences as motives and features within their films. Although tons of critics have discussed the film Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown , I intend to specifically underline two idiosyncratic attributes of it in this film blog, namely the color and the references to Hitchcock's work, within the biographical context of Pedro Almodóvar.

To start with, as the artistic director Antxón Gómez observes, “Pedro works with a very definite range of colors. He has trouble working with white, for example. He always says,'I don't understand black and white.'” According to Oliva (2009), the recognizable use of color constitutes a dominant trademark in Almodóvar's movies, frequently acting in concert with a neo-baroque aesthetic style that is prominent in Hispanic culture. From my point of view, the most astonishing aesthetical achievement in this film should boil down to the various outfit of the leading actress, Pepa Marcos cast by Carmen Maura (see the screenshots below).

In terms of semiology, the color can function as a signifier, which will denote deeper significance namely the signified, the process of which helps us to deconstruct the film as an aggregation of signs. In the first several scenes featuring Pepa, she is wearing a gray suit, which signifies professional and formal; yet after she feels extremely disappointed at her relationship with Iván, the frequent show-up of the color red could manifest that Pepa is the woman “on the verge of a nervous breakdown”, except for once she chooses to wear a blue suit pairing with a white shirt with black polka dots when she needs to be the adult for solving Candela (Maria Barranco)'s problems when seeing the feminist lawyer,where blue delivers a sense of calmness and intellect here (it can be somehow interestingly confusing with the same color constructing different meaning-making —— Candela, the character who represents irrationality and obtrusion, also wears a blue outfit when she shows up in the film for the first time). Furthermore, it is demonstrated by Oliva (2009) that the distinctive understandings of colors of Almodóvar might be triggered by his mother, Francisca Caballero, who made many cameos in his films before her death in 1999; as “bookish "As he could be, Almodóvar shows a sense of sensitivity through repeatedly claiming that his unlimited passion of narrative in the form of colorful visual compositions comes from his mother ——also wears a blue outfit when she shows up in the film for the first time). Furthermore, it is demonstrated by Oliva (2009) that the distinctive understandings of colors of Almodóvar might be triggered by his mother, Francisca Caballero, who made many cameos in his films before her death in 1999; as “bookish” as he could be, Almodóvar shows a sense of sensitivity through repeatedly claiming that his unlimited passion of narrative in the form of colorful visual compositions comes from his mother ——also wears a blue outfit when she shows up in the film for the first time). Furthermore, it is demonstrated by Oliva (2009) that the distinctive understandings of colors of Almodóvar might be triggered by his mother, Francisca Caballero, who made many cameos in his films before her death in 1999; as “bookish” as he could be, Almodóvar shows a sense of sensitivity through repeatedly claiming that his unlimited passion of narrative in the form of colorful visual compositions comes from his mother ——Almodóvar shows a sense of sensitivity through repeatedly claiming that his unlimited passion of narrative in the form of colorful visual compositions comes from his mother ——Almodóvar shows a sense of sensitivity through repeatedly claiming that his unlimited passion of narrative in the form of colorful visual compositions comes from his mother ——

As he said in a speech: “I like to think that my passion for color is not merely a function of the baroque style of my characters, but that it is also my mother's answer to so many years of mourning, in which black was the dominant color. I was her extravagant reaction to the stultifying and excessive tradition of La Mancha (where Almodóvar grows up —— from the author)".

…

"My mother was the territory where everything happened. I learned boldness from her, and something more: the need for certain doses of fiction so that reality can be better digested, better narrated, better lived... It was not a question of complacently accepting things , but of perfecting reality by adding a little bit of fiction."

According to Zurian (2013) that when Almodóvar was eight, his family moved to Orellana la Vieja, a village with few traces of modernity, where he received the primary education under the religious supervision; at 17 he came to Madrid but never enrolled in the Official Film School since it ceased giving classes and gradually closed, then Almodóvar became an assistant in Telefónica, the national telephone company. Albeit lack systematic cinematic studies, he seems to be capable of expressing himself without any established rules; in the universe of narrative and film, his family, especially his mother seemingly leads him to a bigger illusionary world full of vivid colors that are conveying complicated connotations.

Moreover, it seems to have become a consensus in the sphere of film critics that Hitchcock should count as the primary textbook of Almodóvar, aesthetically and industrially; you can still tell new traces of the presence of Hitchcock in the form of appropriation in Almodóvar's movies after accomplishing global success (Acevedo-Muñoz, 2007; Kercher, 2013).

Brill (1988) contended that many characters in Hitchcock's films are victims of the inevitable and fatal traps of their past; conversely, Acevedo-Muñoz (2007) specifically argues that Almodóvar's approaches are based partly on the unstable genre as a metaphor for national identity through direct quotations of Hitchcock's oeuvre, but as a therapy to damage the social diseases from cultural and religious repression in Franco's Spain.

For instance, at the end of Women on the verge , Pepa ultimately reach some emotional firmness when facing Lucía, the crazy mother, who also actively asks to be taken back to the mental hospital after the failed attempt to kill her ex-husband, which is allegorical of the nation's process of recovery; therefore, Almodóvar determined to establish stability and positivity out of the melodrama's natural chaos by making the women exactly be “on the verge” of insaneness , just as the title reads. To sum up, he is trying to pass the positive message that the national trauma could be cured ultimately, or at least offset by presenting that the negativity can be, “paradoxically, a redeeming force”, as Almodóvar himself mentioned in an interview: "I don't want to let even the memory of Francoism exist in my films".

(Word count: 942)

References

Acevedo-Muñoz, ER (2007). Melo-Thriller: Hitchcock, Genre, and Nationalism in Pedro Almodóvar's Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown. In D. Boyd & R. Barton (Eds.), After Hitchcock: Influence, Imitation , and Intertextuality (pp. 173-194). Texas: University of Texas Press.

Allinson, M. (2001). A Spanish Labyrinth: The Films of Pedro Almodóvar . London: IBTauris.

Brill, L. (1988). The Hitchcock Romance: Love and Irony in Hitchcock's Films . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kercher, D. (2013). Almodóvar and Hitchcock: A Sorcerer's Apprenticeship. In M. D'Lugo & KM Vernon (Eds.), A companion to Pedro Almodóvar (pp. 59-88). Chichester: Blackwell Publishing.

Oliva, I. (2009). Inside Almodóvar. In B. Epps & D. Kakoudaki (Eds.), All about Almodóvar : a passion for cinema (pp. 389-445). London: University of Minnesota Press.

Townson, N. (1988). The Spanish Labyrinth. New Statesman & Society, 1 , 40.

West, D. (2013). A companion to Pedro Almodóvar. Choice, 51 (4), 644.

Zurian, FA (2013). Creative beginnings in Almodóvar's work. In M. D'Lugo & KM Vernon (Eds.), A companion to Pedro Almodóvar (pp. 39-59). Chichester: Blackwell Publishing.

View more about Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown reviews