I don't know who translated the name "The Elegy of the Country Folk", but I think it's too bad. In "Webster's Dictionary", Hillbilly's explanation is:

“A person who lives in the country far away from cities and who is often regarded as someone who lacks education, who is stupid, etc.”

Literally, the word means "hillie", but the "countryside" in the United States is too far apart from the "countryside" in China. The Chinese countryside refers to the peasants who face the loess with their backs to the sky, and the lower class that the "urban people" want to correspond to; but in the United States, the difference between class is not in urban and rural areas, but in race. The term Hillbilly first specifically referred to the mountain dwellers in the southern Appalachian Mountains, and later expanded to Alabama and other central and southern regions, and was later "recycled" by the media, referring to a slang term translated into a literal "countryman" "It not only confuses Chinese readers into the Chinese countryside that they take for granted, but also adds a layer of seriousness to the written language, coupled with the "tragic song" at the back, which makes people feel baffled, thinking it is an Iliad-like Homeric epic.

In fact, the translation of this word is very simple: fellow.

Northeastern villagers, Jiangxi villagers, Shaanxi villagers, Taiwanese villagers... Don’t let them represent their origins (like the author JD Vance’s hometown of Kentucky), but also express their background of leaving their homes and working hard in the cities, becoming industrial workers and declining history. The word "Elegy" was originally a proper noun in Greek mythology, and I feel that it does not fit the Chinese context. It is better to call it "Cry of Blood" or "History of Blood and Tears". "A History of Blood and Tears", does it sound like it? Feel a bit "alive"?

The most important thing about the original book "The Elegy of the Country People" is that it is essentially a class autobiography of the American working class. From the KFC countryside to work in Ohio, Vance’s family has experienced poverty, migration, industrialization, and poverty again. From the writing of Vance, who has successfully crossed classes, it is said that Trump was unexpectedly elected the first president of the United States in 2017. Published in two years, it seems particularly significant for the times. Where do the workers in the rust zone come from and where are they going? Why did they give up the Democratic Party, which they have supported for many years, and embrace the Republican Party? This book appears to be family style on the surface, but it is actually class history. The class transition of Vance was only an exception in the family. He could become a Marine, earn high college tuition, and enter Yale Law School to become a JD, something he couldn't even imagine in his childhood. And this leap gave him an outsider's perspective, and then re-examined his past life environment, giving the story a dual perspective, like Liu Qiangdong went to write Suqian, Jiangsu, and Xu Jiayin went to Zhoukou, Henan.

The success of the book is also the absence of the movie, and Vance's torture of the roots of society. The book is about the fragmentation of the American dream: why did a family become industrial workers and their efforts to escape poverty ended up in vain? Why do they try to live like the middle class but not get it? Where is the root of the blue-collar degeneration and poverty? What is their future position in American society? None of these problems are shown in the movie. The film made class history into personal history and family history into family history. This is of course partly due to the limited space of film and television language, but it also shows the narrowness of the director's perspective. The story itself is still very beautiful, and the rhythm of the narration is not a problem. The performances of Vance's mother and grandmother make people feel moving, but this is far from the whole story.

This reminds me of Zhang Meng's movie "The Piano of Steel" a few years ago. Perhaps in the Chinese context, the name is much better than "The Elegy of the Country Folk": an industrial worker from the Northeast wants to build a "steel" piano for his child. There is poverty and tenacity in this name; there is a narration of the background, there is a sympathetic irony, and there is a yearning for spiritual life. There are many birds with one stone, great.

Compared with the realistic (and beautiful) background of "The Elegy of the Country People", under Zhang Meng's lens, the entire Northeast Heavy Industry Zone presents an old covenant-like eschatological mood in Western literature. Daylight shines through the dilapidated Bauhaus building, into the barren weeds and paint mottled steel in the abandoned workshop, and the spot of light flickers on the lens. I have never seen anyone photograph a bankrupt factory so beautifully, as if this is not a dilapidated factory, but something with life, and the machine assumes the function of making this organism dead and not stiff. The sparkling molten steel under the dilapidated surface, the trembling crane, and the swinging balance are all part of this organism. People can see that its seemingly non-existent vitality is hidden under the layers of garbage, as if The dormant behemoth does not know when it will erupt.

The shot of "The Piano of Steel" is simple and the editing is straightforward. Many exterior shots used wide-angle shots directly on the facade of the building, like a two-dimensional painting, condensing the sense of time and space, and the characters inside are as small as supporting actors in the painting. The appearance of the characters is also strange: their background is always empty: no pedestrians, no street scenes, no extras. Some are just dead branches after the snow, steaming briquettes stoves, empty streets, and dormitory buildings with mottled vistas. It seems that this city and these factories are falling down amidst the roar of the explosion, just like the two big chimneys that the old engineers who stayed in the Soviet Union tried their best to keep, decayed and silent forever.

His editing is as straightforward as the camera. For example, after Chen Guilin borrowed money and bumped into walls, the next shot was to steal the piano; and after stealing the piano didn't work, the next shot was to start looking for an artificial piano. But he is not the only subject of piano making.

Some people say that China has the best industrial workers in the world. Their fingers are flexible and the lathes are exquisite, which is a craft handed down from generations of masters. After the 1980s, these technologies lost to the rising tertiary industry, then the IT industry, and later the bubble-booming financial industry. Those craftsmanship that existed in our childhood minds were presented in the most romantic form by Zhang Meng, bringing a sad end to these apocalyptic industrial workers. These workers, they are our fathers, they are our mothers. When our father was a child, he could use waste wood to make small horses for us, and our mother could knit sweaters of various colors for us with dexterous hands. They used scrap parts to make a spinning top, and they welded an iron flower out of molten steel. Specific to the individual case, my father used wood scraps to make a battery lamp, which was used to illuminate the era when the power was cut off from time to time. The battery inside came from my mother's factory. When I was a child, I used to go to her workshop to string battery covers for the aunts, listen to the female workers chatting, and smell the tar. These techniques became useless in the wave of the times, until Zhang Meng's camera.

He could have been more sensational, like Jia Zhangke in "Twenty-Four Cities", let the interviewee tell the story of the year. But he did not do so, and even deliberately avoided sensationalism. When Xiao Yuan stood in front of his father, I would cry as long as the camera took a few more seconds, but he suddenly turned the camera to other places. This is not fabricated, this is their life. His shots live among these workers.

The sound of the "steel" piano was unpleasant and vague. But to the father and the workers, it was the best voice in the world. At the end of the film, there is a sense of symbolism. Qin Hailu shook her coquettish dance skirt like Carmen, playing the final hymn of the industrial workers before the curtain call.

Of course, the time span and volume of the story of "The Piano of Steel" and "The Elegy of the Countryman" are far different. The piano is a sketch, a story, and a three-in-one interpretation of a drama; the tragic song is a history that crosses the ages, and a person’s growth has a completely different style. But the piano can be big and small, and let the audience understand-at least feel-the decline of Northeast Heavy Industry. These are tragic songs that are far from reach.

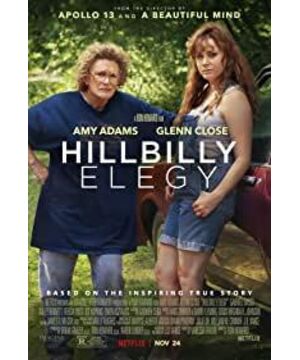

View more about Hillbilly Elegy reviews