The small village began to exert its strength overnight, and when the daughter of the Chimei village chief appeared (I already knew she would appear unexpectedly), I was still deeply moved. There is a powerful echo of the classical spirit. Such as Chekhov or something. In his suffering novels, at a certain time, there are also such women or children who come forward to save.

The hiding of the story, as well as the reflection, is done very well. The progress of reality is so dry and boring, but the looming stories outside of temporal space and time are silently sneaking. Active and poetic.

Sometimes, those stories are even just a few black and white photos. In those photos, going back in time, only the old observer in front of the mirror is left.

The observer (or the role of an out-of-the-art intellectual) has always appeared in Ceylon movies. That person is a doctor in this movie. I don't know why, in my imagination, Dostoevsky is like this. It's just that this doctor seems to be more melancholy and calmer than Lao Tuo. Always in a daze, talking to myself in my heart. But it also brings us new discoveries about daily life.

Sometimes he went back to his doctor's office in a very tired afternoon, and then the camera was shaken out and saw the red sunlight shining on an unmanned balcony opposite the office. There seemed to be some clothes to dry on the balcony, as well as plants, and some meaningless supports. But at that moment, we felt hopelessly that life had fallen.

We are always thinking of fleeing, but where should we flee?

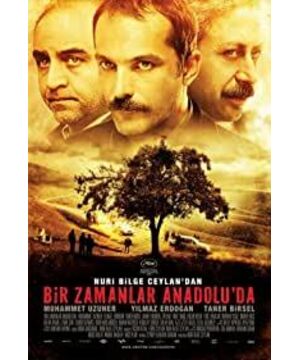

View more about Once Upon a Time in Anatolia reviews