Apart from the usual elements in Wu's films, he also added the background of the Hong Kong turmoil and the Vietnam War in the 1960s and 1970s, under such an era background. Cruel but full of temptation, the long changing times provide sufficient support for changes in friendship, intimacy, separation, and rupture. The audience can also feel the vicissitudes of life.

Ah B, Ah Rong and Ah Hui are good friends who grew up together. Ah B got married, Ah Hui went to borrow a usury loan to hold a banquet for Ah B, but was robbed by the rogue Ah Qiang. Ah Hui vowed to get the money back, but he Was injured by Aqiang. After Ah B found that Ah Hui was injured, he and Ah Hui went to find Ah Qiang to settle accounts on the wedding night. During the fight, Ah B missed and killed Ah Qiang. In order to evade legal sanctions, B, Hui, and Rong had to leave Vietnam. The three were in Vietnam. With the help of Ah Rong's distant relative Ah Le, they robbed a batch of golden pages. When the Vietnamese corrupt officials sent people to hunt them down, they were mistaken for spies and arrested by the Communist Party of Vietnam. Ah Le arrived with the U.S. military, and the war was raging. Ah B was shot and rescued by the monks in the mountains.

After Ah B recovered, he went back to Saigon to find Ah Lo. He learned from Ah Lo that Ah Fai was shot in the brain and the bullet could not be taken out. He became a mentally disabled man who traded drugs for pain relief by being a killer. The one who shot him was Ah Rong, who had been greedy for a box of gold. In order to relieve Ah Hui's pain, Ah B reluctantly killed Ah Hui and returned to Hong Kong with Ah Hui's skull to make a complete break with Ah Rong. The two brothers who once lived and died together fought fiercely to resolve all the love and righteousness. hatred.

The film's character structure and the design of some scenes were obviously influenced by the American Vietnam War film "The Deer Hunter", especially the paragraphs where the three were captured and forced to kill. In the scene of the Vietnamese military and police suppressing civilians, it is easy to think of the 1969 Pulitzer Prize-winning work "Shooting Prisoners of War".

At the beginning of the film, that camaraderie, or another expression—loyalty, is dazzling, overbearingly happy. The impulsiveness and vitality of youth will infect everyone, the kind of carefree, happy and grudge-like perfection. And when the perfect shell of the dream peels off, our hearts will feel convulsions...

A Rong, who is addicted to gold, abandoned his friendship for more than ten years and betrayed desperately, in fact, he is destined to be punished. All we can do is watch silently as the crack grows and becomes irreparable. He didn't do anything wrong, he just wanted to change his life and went mad about it, but betrayal is unforgivable.

Revenge is finally completed in the flashbacks that are constantly cut in, but there is no revenge-style pleasure at all. When Ah B killed Ah Rong, he looked up to the sky and howled so that the viewer could see the so-called hero's suffering and the ruthless fate in the blazing flames. The tragic result, and finally everything is frozen in the understated music.

In all honesty, "Blood on the Street" has a more profound reflection than the "True Colors of Heroes"-style hero film. "The True Color of Heroes" focuses on the heroic elegy of people who are unwilling to sink in adversity at the mercy of fate, and try their best to resist. In "Blood on the Street", the protagonists can't help themselves. Under the torrent of the big era and the mercy of fate, they are exhausted and run for their lives, but it is difficult to escape.

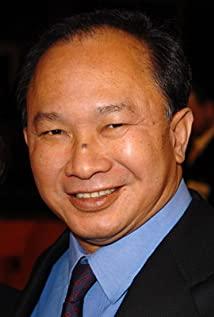

Unexpectedly, Hong Kong movie audiences who are tired of the new and the old are tired of the heroic films of love, hate, blood and blood, and turn to comedy films such as "The Gambler" and "The Gambler" starring Stephen Chow. Just over 8 million. In the 1990 Hong Kong Film Awards, "Blood on the Street" won several nominations such as Best Director and Best Supporting Actor (Jacky Cheung), but in the end it was defeated by "A Fei Zheng Zhuan", which was in full bloom that year, and got nothing. The disheartened John Woo was invited to Hollywood to break new ground after directing the market-oriented Chinese New Year comedies "Across the World" (1990) and "The Detective" (1992).

Heroes and anti-heroes, friendship and betrayal, departure and return, this film that John Woo really worked hard to create did not make much waves in the noisy and impetuous Hong Kong movie circle, and eventually disappeared. This has to be said to be an embarrassing thing.

View more about Bullet in the Head reviews