The title comes from Freud and his successors, which was originally subtitled "What is the Cause of Psychopathology: Trauma or Fantasy?". The phenomena involved here cannot be called psychopathological, but I feel that this example can be demonstrated from a similar logic as to why we think fantasies -- ideally good or ideally bad -- It's all something to be wary of.

"People need a scapegoat." The "need" in this sentence is the word that I find most meaningful. It reminds me of the "paranoid-schizophrenic position" in Melanie Klein's object-relations theory: infants in this position, because of their immature self-development and inability to digest the anxiety caused by the frustration of their instincts, must turn their aggressive drive away. And libido is projected separately, forming a distinct "good object" and "bad object" inside. Klein argues that successful disintegration—having an initial, uncontaminated inner image of the good object—is a prerequisite for successful integration.

I think a similar logic can be used to explain the Jewish outcry that Arendt received after his theory of banal evil. For the Jewish community of angry protests, their ego is in a weakened state after a great trauma, and the realization that "everyone may give up thinking and do evil under certain circumstances" paints a picture of Terrible picture: It hints at the underlying universality of evil and trauma. Everyone around you may be a villain under certain circumstances, and every moment of your life may be a traumatic situation. And the pervasive anxiety implied by this realization is that they have experienced collective trauma, the weak ego is unable to deal with it, so they regress to a "paranoia-schizoid" in a way as a protection for the ego . Eichmann must be a demon: for pure good can exist only when pure bad exists.

Such division is a defense, but not pathological; it is necessary. When the ego does not have sufficient strength, it will be overwhelmed if there is no defense. Therefore, I think that the violent protest of the Jewish community against Arendt is not only completely understandable, but also a necessary process.

Arendt is a brave person, and her greatest courage lies not in her ability to insist on expressing her opinions in the face of external opposition, but in her ego being strong enough to look directly into the darkness that exists within everyone : Under certain circumstances and times, it is entirely possible that you and I are also Eichmann. It is very valuable to have such courage, but we cannot ask the Jews of that time to possess such courage. Therefore, I think the real Arendt should have no expectations in her heart. When she writes such an article at such a time node, it will trigger a real academic and rational debate. If she does, like in the movie, hold her head up when the editor says she shouldn't write Greek, "then they should learn it", that's where I'm really a little disappointed.

So in terms of her character created by the movie, what touched me the most was not courage, but a small detail: when her husband opposed her and replied to those who wrote to protest her, the reason she gave was not "what they said" No", but "I hurt these people deeply" . Regardless of whether she publishes articles to practice her view that "rational academic thinking should not be buried under external opposition," she still shows her natural sympathy and instinctive concern for people. This is the most important. A good philosopher and ethicist must be a person who is sensitive and can still have a soft heart in the face of the cruelty and complexity of this world. Just like the warm dialogue between her and her husband:

"How could you just leave without kissing me or kissing me?"

"When a true philosopher is thinking, he cannot be interrupted."

"But they can't think without kissing them."

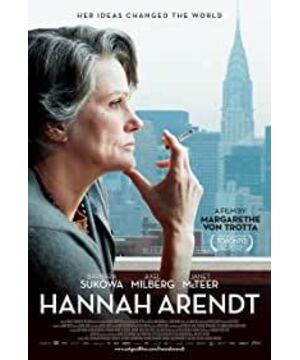

View more about Hannah Arendt reviews