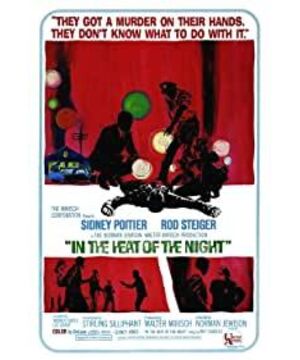

Oscar's BEST PICTURE obtainer, Canadian filmmaker Norman Jewison's IN THE HEAT OF THE NIGHT pluckily wrestles with the racial tension through a black-skinned homicidal detective Virgil Tibbs (Poiter), hailed from Philadelphia but stands up like a sore thumb in a southern town Sparta in Mississippi, where a wealthy industrialist is murdered.

Virgil is wantonly brought to the local police station as the chief suspect in the first place, by a vacuously cocksure officer Sam Wood (Oates, conspicuously poses with an air of casual small-mindedness), a decision precociously conducted simply owing to Virgil's skin color , albeit he is garbed in suit-and-tie, Sam instinctively deems this black guy is the murderer without even questioning him, assumes that he awaits fleeing in the train station at 3 am Virgil remains cooperative under duress, only to manifest his ace in the hole with his police badge, in front of the sheriff Gillespie (Steiger), the first slap in the face.

While it seems arbitrary that Virgil's superior would patly ask him to assist the investigation by phone, but the sticking point soon boils down to Virgil's decision of leaving or staying (due to the rampant hostility from local peckerwoods), a seesaw game well played between Virgil and Gillespie, each turnabout marks a shifting progress in their respective cognition towards each other, in tandem with the ongoing police procedural. But admittedly the unfolding crime-solving routine doesn't crop up completely creditable as the film's renown attests. Virgil is way head and shoulders above his peers born with lighter-complexion, in certifying facts and sifting out clues (and might even be endowed with some psychic ability, otherwise how could he be so sure about Sam's veered routine? A snag the film never cares to elucidate) .The only foible is his preconceived bias, which is accountably shaped up by hardened racism he has to come in for on a daily base, and near the climax, he admits it frankly and timely swerves to the right track in teasing out the hidden perpetrator.

Tellingly, what makes the film"culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant", cited as its induction in the United States National Film Registry in 2002, is the palpably construction of the foe-to-friend transition between these two men, but not in the modality of indoctrination or spoon-feeding, today's audience might find it beggar-belief to some egregiously blinkered presentation of racism (which could very much be the case as we twig half a century later, the canker has never ceased to incubate), however , not for one minute, we have to stretch our suspended disbelief in view of the two men's mutual conflict-and-reconciliation, a sensibly crafted understanding-vanquishing-prejudice which can be related to every spectator, it is the very basic technique in storytelling : be relatable without resorting to simple preaching,but to round it out in all its integrity and empathy, it is another matter, in this sense, the film merits all the accolades it garners.

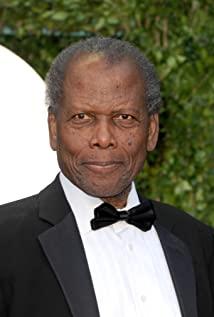

Rod Steiger won Oscar's BEST ACTOR trophy for his bellowing imposition and everyday toiling amplified in high voltage, but in hindsight, it is hard not to attribute his triumph (at least to a degree) to the inexorable gesture of urgent political correctness. Sidney Poitier, by contrast, takes on a subtler but no less dramatic seething-and-smouldering performance to the fore in his trailblazing embodiment for his own race, a crusade he pulls his back into with unalloyed dignity and honesty. Lee Grant, in a small but pivotal role as the newly widowed rich wife from north, choreographs a most revealing pas-de-deux with Poitier in their first scene together, gives a chilling vibe of the congenital racism even from those who are ostensibly liberal-minded, the poison is like old habits, roundly die hard.

An opportune tirade spiked with oomph (tantalizing nudity is included), oompah (courtesy to Quincy Jones' throbbing score and Ray Charles' theme song) and moxie (robustly edited by Hal Ashby who was received his first-and-only Oscar statuette, which might facilitate his transition to the director chair), like Stanley Kramer's INHERIT THE WIND (1960), IN THE HEAT OF THE NIGHT needs to be mandatorily watched by every single human being if we were living in a perfect world, simply because there is cardinal verity in its story that no other belief can twist or garble.

referential points: Jewison's FIDDLER ON THE ROOF (1971, 6.4/10), MOONSTRUCK (1987, 7.6/10); Stanley Kramer's INHERIT THE WIND (1960, 7.7/10)

View more about In the Heat of the Night reviews