An Unofficial Guide for Refugees

A homeless Romanian man travels a long way from his farm, via the Balkan Peninsula, the European Plain and the English Chanel, and finally arrives in England. In England, he takes great pain in finding a job and ends up in working in a remote farm in Yorkshire, where he falls in love with the son of the farm owner. The love turns out to be fruitful, despite obstacles and difficulties within, as he decides to stay in England permanently, in the name of love. If there had been such a story written one hundred years, or several decades ago, the story would have been Dracula (1897): An Englishman travels to Transylvania, where he meets a devil, who prisons him and takes a ship to Yorkshire afterwards. Powerful yet mysterious, the devil attempts to menace England by occupying female bodies and the land,but when his conspiracy is revealed he flees back to his castle in Transylvania, where he was demolished by a team of European men.

The two stories mirror each other on the two ends of the timeline of more than one century as they both reflect the anxieties of England in the two different times—in the late nineteenth century, the Britain at its imperial peak was concerned about the alliance between Germany and the Austria-Hungarian Empire, where as in the early twentieth century, England, which has lost its empire for long, is struggling to grapple with immigration policy, economic decline, and social transformation in a more globalized world than ever. This contrast makes the whole movie looks like such as story: in the most English Yorkshire there is a family where the mother is absent, the father is ill, the grand mother is old, and the only son is sluggish, idling, and gay. The family is to be saved by a man from Romania, who is strong, diligent, and skilled.To a certain extent, this could be a metaphor for today's England: the left-wing director obviously hopes that embracing new immigrations actively would rejuvenate Europe and give it a new start.

Interpreting the story on this level would miss deep confronts in the movie. Dracula in the late nineteenth century has a spatial relevance—between the two ends of England and Transylvania are the European continent and seas, only travel connecting them. On the one hand, travelling, and associated mobility and technology, in the period of imperialism in the late nineteenth century was one of the benefits of modernization, in particular European modernization (we should not forget that it is the Englishman who travels to Transylvania in the first place, and it is by ship that Dracula arrives in England. Traveling was a channel that links the remote, uncivilized world in East Europe with the centre of the world, London. On the other,the links created by travel in this time was necessarily embedded in the tropes of English travelogues over the centuries. Transylvania, as its name indicates, has long been regarded as a place beyond the forest, beyond the rivers, connected to Asia (Islamic Asia) , where not civilization exists. Only in this spatial differentiation by the measure of imperialism and civilization can we understand the creation of a demon land in Dracula. From an Orientalist perspective, it is the deafferentation premised on imperialist hegemony that tells the story of Europe/ the Europeans and the Other.Only in this spatial differentiation by the measure of imperialism and civilization can we understand the creation of a demon land in Dracula. From an Orientalist perspective, it is the deafferentation premised on imperialist hegemony that tells the story of Europe/the Europeans and the Other.Only in this spatial differentiation by the measure of imperialism and civilization can we understand the creation of a demon land in Dracula. From an Orientalist perspective, it is the deafferentation premised on imperialist hegemony that tells the story of Europe/the Europeans and the Other.

Turning to the movie, it is not difficult to find how the tropes of traveling, space, and identification with the Other are persisting in the whole narrative of the story. For example, we know nothing about Gheorghe. Whereas the movie provides credibility markers form John's story—his family location (Yorkshire), his age, his accent, his surname, his occupation, his past, his education background, even his psychological issues, etc., it rarely depicts who Gheorghe is. We barely know anything about his surname, his age, his hometown, his family, and even his nationality. When they meet for the first time, John thinks he is from Pakistan, but he soon corrects it as Romania. But does this even matter? For John, it does not obviously, because he never shows any interests in Gheorghe's hometown; and for Gheorghe himself,it does not either—every time when talking about his hometown his depictions are always vague and the place is thus unidentifiable: it is a place with beautiful spring, probably a waterfall as well (even the waterfall is more iconic for Romania than his hometown ) , and it can be Romania, and Pakistan, as well. We know that he comes from Romania, but how, When, and why? It is in the travel between places (Romania and England) that truly reveals the tensions within the whole story : Gheorghe's is not only new, but strange; His travel would make the beginning of a new life, for John, for John's family, and even for himself, yet necessarily disconnecting him from his past and his hometown, wherever it is. He is the Other, being transformed into one of us.While dangerous Dracula who attempts to reign England has to be killed with his earth back to Transylvania, harmless Gheorghe can stay in England permanently, only at the cost of his past. In England and in this family, he is always welcome, as long as he is strong, diligent, and skilled, and willing to give, no matter who he is.

19/04/2018

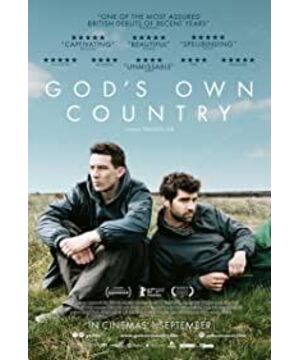

View more about God's Own Country reviews