Even if this film is placed on the coordinate axis of Ceylon's film work, this film is a big leap compared to his predecessor "Three Monkeys". If "Three Monkeys" is his attempt to get rid of the previous film Aesthetics has influenced him, and we can say that he has established his own film aesthetics perfectly from the "past events". I even suspect that because of the contingency that this movie script is based on a real story in life, his future works may not be able to surpass this one.

Why this film is called Niu, because it is the dual embodiment of the director's own film concept and his first-class execution, it is the perfect combination of film neo-realism and long-lens aesthetics.

What distinguishes film from life is that its series of unique artistic means centered on montage is based on warping time. So usually movies show viewers splicing and distorting lives on a timeline, and often time in movies passes much faster than real time. However, shooting according to the real time is often a mere record, losing the charm of secondary artistic creation.

The Anatolian past is a perfect example of Ceylon's solution to this problem. The story sequence of the entire film takes place in a 20-hour period from late night to early morning. Apart from the necessary skimming of unrelated time segments, the time the viewer is watching the film is 1 to 1 compared to the time of the actual story. And it's different from mere documentation, thanks to the film's skillful and sophisticated long-take scene design. A large number of metaphors, dislocation and substitution of characters, inevitably create a certain threshold for viewing this movie.

Usually in a crime-solving movie, the information the audience gets from the movie is the sum of the perspectives of all the characters in it. The reason why the audience is nervous or the thrill of getting the secret comes from the asymmetry of information between the audience and the protagonist in the movie. But this amount of information does not actually exist in real life, and we cannot all be directors or gods in our lives. In this film, all the information the audience is presented with is based on what the doctor says is present or can be seen from his point of view, and what he gets from other people's conversations. Some are direct facts, and some second-hand information from conversations needs to be stripped away to get to the truth. In this film, the audience is directly placed by the director in the real time of the role of the doctor. In order to firmly uphold this principle, Ceylon has abandoned many of the traditional methods used by the film to capture the audience's interest, such as the suspect's death while resting in the village. Suddenly confessing this paragraph, because the doctor is not present, the audience can only speculate what happened inside through the foreshadowing before and after.

The original motivation of the whole story was to find the body. In a tired night, the plot was like Bong Joon-ho's ubiquitous frustration and bifurcation. What the audience wanted to know most at first was to analyze the retrospective and motives of the criminal's murder after finding the body. At the end of the whole movie or these initial key points, there are still a lot of blanks, and the life secrets of everyone in this group of people who are looking for the corpse surface more or less unintentionally. Finally, the whole society is presented to everyone from top to bottom. The lower living beings. The whole story is left to the audience about whether we should ask the truth about things in real life, and how we should judge other people's actions as right or wrong. If we directly put ourselves in the role of a doctor, this is what Ceylon thinks of an intellectual who is unavoidable but unable to have a sense of mission to the society in an urban-rural fringe where there is a gap between the rich and the poor and a clear class stratification. From this point of view, how similar Turkey and China are.

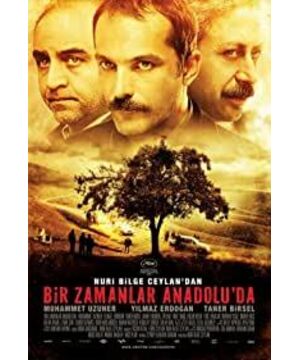

View more about Once Upon a Time in Anatolia reviews