At first I was quite dissatisfied with this attitude of diverting the issue. Something went wrong in Japan, saying "there are more problems with China and South Korea" cannot solve the problem, it just shows that this person does not want to solve the problem. But while the rebuttals that many Japanese made in the face of the bloody evidence reminded me of their attitudes toward the Nanking Massacre, I have to admit that the most thought-provoking thing about this film is not about dolphins and whales. Like the Japanese who transferred the problem, I also thought elsewhere. Because although I am extremely opposed to the dolphin slaughter and am extremely indignant at the atrocities of the Japanese army's aggression against China, I can't think that the Americans who made this film and most of the Chinese (including myself in Japan) know much about Japan.

If the film was an academic paper, how extreme would it be? There is no right to speak to the object being opposed at all. In the end, no matter which side of justice is on, movies are nothing more than a tool for propagating claims and gaining recognition through all kinds of pretense. Academic papers will not have such a large impact, and the one-sided complaint of the film, it is difficult not to make people suspicious.

Today, I saw a comment written by a Japanese person, which mainly revolves around a "right to be foolish" - people have the right to do stupid things without harming themselves. The author believes that Americans are tolerant of internal folly, but the opposite is true for external, while Japan is the opposite of the United States, strict on the inside but lenient on the outside. The implication is that Americans like to interfere in the internal affairs of other countries (and Japan is magnanimous in not clearing out suspicious people).

It is a pity that the author did not take into account the "premise of not harming yourself" (eating dolphin meat is said to cause mercury poisoning), and apparently did not know much about the whaling industry. But he used quite mild language, once again expressed the voice of the Japanese: you don't even know us.

You don't even know us. This is the most powerful sentence in all Japanese words. The Asahi Shimbun interviewed local fishermen and officials after the film won the award, and everyone said this sentence in unison. Unfortunately, I, who agree with their opinion and look forward to their own statement, have not seen any explanation for this sentence.

Why did the Japanese hunt whales? Why are dolphins allowed to slaughter locally? "Tradition"? "Tradition" does not mean "immutable things". This doesn't answer the question. Could it be that "tradition" actually means "unspeakable"? It turns out that after saying so much, the Japanese have not defended themselves at all. Not defending, does it mean guilt? Or is it just, you don't even know us?

And when the unilaterally complaining Americans meet the unspeakable Japanese, there is a scene of Ric protesting silently in the crowd of Tokyo streets. I don't cry for dolphins, I cry for those who love dolphins like this, and for the truly silent Japanese.

Humans can feel a certain resonance with dolphins, but they cannot realize the communication between human hearts.

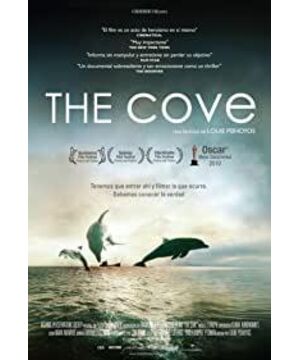

View more about The Cove reviews