Film review assignment for introductory religious studies class. yysy, some Indian movies are really good and deep.

Is the object of belief "God" or "Religion"? From a common atheist point of view, this way of asking may be somewhat redundant, because the relationship between the two options involved in the question does not appear to be in opposition or juxtaposition, but rather includes: In this view, "Religion" is generally understood as a "system of belief and practice"; and since belief is always directed to a particular "religion", then belief in "a religion" naturally implies a belief in that religion The belief in the "God" corresponding to it is a series of beliefs including "belief in the existence of God". Atheists with this view are often confused about religious beliefs, and even believers of different belief systems have a tendency to fail to understand each other. [1]

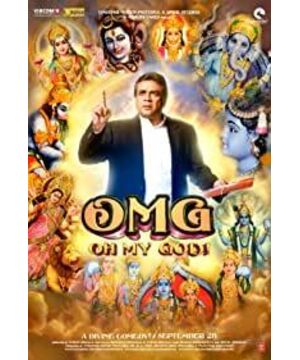

In this sense, the 2012 Indian Bollywood film "O Divine God" can be regarded as an ingenious answer to the above question. The plot of the film itself is very simple. The Indian businessman Kanji's shop collapses in a bizarre earthquake and he personally sues the gods for reparations; but in the process, Kanji himself is remarkably transformed from an atheist. became a believer. "God Drops" shows its audience the transformation process of the same character from a religious "spectator" to a "believer", thereby clarifying the core of understanding religious life, that is, an irreducible, first and One-person "faith" phenomenon. In this sense, this paper believes that for believers, the object of belief is directly "God/Sacred/Spirit", rather than "religion" from a third-person perspective (the core of "religion" is irreducible "belief" ); at the same time, for bystanders, a better understanding of religious phenomena also needs to rely on the first-person understanding of the phenomenon of "belief" (the concept of "religion" based on the understanding of "belief" needs to be changed). This article will be mainly developed in two parts. First of all, this article will combine the analysis of the film to clarify the first-person characteristics of "belief" as a divine manifestation, and preliminarily explain the above-mentioned relationship between "belief" and "religion"; ” concept in an attempt to explain the historical factors in the formation of this concept of “religion” (as mentioned at the beginning of this article), and to further illustrate that “belief” is not only critical to understanding the experience of individual believers, but also helps to understand Even change the religious life of a wider group.

(one)

In this section, this article will firstly (1) analyze Kanji's defense strategy in court, pointing out the difficulty in explaining "God" through "religion" in his argument. (2) Secondly, this paper will illustrate the meaning of the divine from the perspective of phenomenology and explain the above difficulties with the help of Iliad's discussion on theophanic dialectics. (a) On the one hand, the experience of the appearance of “spirits” itself is an irreducible first-person phenomenon. Combined with the analysis of the changes before and after Kanji’s conversion, it can be shown that “belief” has a kind of directness. (b) Therefore, "religion" and "spirits" are themselves objects from two different perspectives. For believers, "spirits" are directly manifested, while "religion" is based on this experience. The observation product from the third-person perspective; at the same time, since theophany always occurs in a specific historical environment, the same "god" may manifest itself in different forms of belief and life.

(1) In the movie, Kanji tries to appeal to the insurance company, but the devious insurance company claims that the source of the earthquake is divine providence and does not provide compensation for "inhuman" damages. Knowing that there was no hope of suing the insurance company, Kanji turned to sue the gods, hoping to prove that the earthquake was indeed caused by the gods, in order to obtain compensation. However, if Kanji's argumentation logic is examined more closely, it is not difficult to find that there is a considerable contradiction, and this contradiction stems from the tension between the sacred and the secular. Judging from the plot in the film, if Kanji wants to show that it is indeed the gods that caused the earthquake, he needs to prove the following two propositions, namely (A) "Gods" exist, (B) and "Gods" are bad, or " gods" (for other reasons) to cause earthquakes (i.e. to illustrate cause and effect). However, Kanji's defense strategy here is questionable: in most stages of Kanji's defense, he bypassed the discussion of "the gods themselves", and put the core of the argument on the doctrine of the believers of gods. a special group of monks or priests.

Kanji's argument in court is primarily directed at proposition (B), which can be grossly themed as follows: (A') According to empirical evidence, monks or clergy (and their organized activities) are bad, i.e. "religious "it is bad. (B') Therefore, "gods" are also bad. [2] This paper believes that there are certain problems in the derivation from proposition (A') to (B'). On the one hand, if there is a logical implication of value/moral judgments about two objects (i.e. "if A' is good, then B' is good"), it seems necessary to state that A and B are either semantically identical or Empirically identical; otherwise, it would be difficult for us to imagine why the value/moral judgments of these two different objects of experience could necessarily be consistent. However, if the value/moral judgments of two objects are not logically consistent, then it means that separate judgments are required for the two. However, it can be found that since the empirical evidence provided by Kanji can only support proposition (A'), at the same time, Kanji's argument lacks the elaboration of the relationship between "God" and "Religion", or the separate discussion of "God" itself , so that the judgment of proposition (B') can only be regarded as a kind of assertion, so it cannot explain that the gods are responsible for the earthquake.

Here, a question worth pondering is: how can Kanji talk about "the gods themselves"? We find in Kanji's argument that there seems to be an insurmountable gulf between "religion" and "gods": in what sense can a narrative of "religion" be applied over "gods"? Does the corruption of "religion" imply that there is something wrong with the "gods" themselves, and likewise, is it possible to directly understand the actions of "gods" themselves without resorting to scriptures? [3]

(2) The above analysis reveals that the core difficulty in Kanji's argument lies in the way in which "spirits" and "religions" are related. Before exploring this issue in detail, this article attempts to first interpret Mercea Eliade's "theophanic dialectics": by analyzing Eliade's phenomenological explanations for key "divine" features in religion, we can Get a better grasp of what the concept "spirit" might mean. In the view of this paper, humans live in the world and interact with objects in the world and with each other, and there is no object itself that is simply "what it is": the object is always defined and confirmed in an interactive relationship, and at the same time Always present in a meaningful way. The "sacred" that Iliad discusses here is a special meaning of religious objects: it manifests itself in worldly and worldly life, and presents a dialectical relationship with the world.

On the one hand, the sacred is a quality that is opposed to the secular, but the sacred cannot be presented in a non-secular, holistic form, but must manifest itself partially through the secular; on the other hand, although the sacred manifests itself in the secular , but it can always present a side that goes beyond the secular, thus implying the non- secular attributes of the divine itself, a larger whole that transcends parts. [4] Take the black stone symbolizing Shiva's penis in the film as an example. On the one hand, although this stone is only a mundane thing on the surface, a divine manifestation means "a choice, which means manifesting this as a A sacred thing is clearly distinguished from anything else around it." For the believer, the black stone acquires a whole new dimension of the divine, symbolizing the present manifestation of Shiva (the penis) as divine itself; but On the other hand, the black stone chosen at this time is not identical to Shiva himself, because every manifestation is an "inadequate manifestation", a part of the whole. [5]

This understanding of the divine-secular dialectic is crucial. (a) Before further explaining the aforementioned connection between “spirits” and “religions”, this article believes that it is necessary to add and note that in a theophany, the manifestation of divine characteristics in tangible objects is itself a fundamental and direct , First-person experience that is irreducible to third-person narration. [6] An analogy can be drawn here to consciousness in philosophical discussions of mind: from a common materialist point of view, since consciousness can always be "reduced" to a corresponding neurophysiological phenomenon, the state of consciousness is actually Equivalent to brain state (heart-brain identity theory). However, this view ignores the fundamental first-person character of consciousness. The third-person description of color as "the spectral signature produced by the molecular structure of an object's surface under incident light" does not equate to the subjective experience of seeing color, i.e., "what-it-feels-like" ; although a visually impaired person can understand the neurophysiological patterns of a color-impaired person, he does not really "know" what the visual experience of the latter is like. In this sense, consciousness has phenomenological reality.

Similarly, for religious phenomena, believers’ experience of “theophany” and the first-person experience in belief cannot be replaced by third-person descriptions; however, what is different from philosophy of mind is that the understanding of neurophysiological phenomena itself is not Consciousness is required, but belief is always fundamental and fundamental if religious phenomena are to be better understood. Wilfred Smith, in The Meaning and End of Religion, describes this as an intellectual statement such as a doctrinal formulation, theological system, or creed (as well as a range of religious phenomena including art, religious organization, and ritual). A good understanding of ) ultimately needs to include a view of "referring to a transcendental reality through man's inner life". [7] In Faith, each individual is associated with infinity in a thoroughly involved way, and if one ignores the fact that there is a transcendental element (or "theophany" as Iliad calls it), Then these religious phenomena will be unexplained. [8]

Going back to the film, we can more intuitively understand the fundamental difference between Kanji before and after the transformation. Before having faith, Kanji's understanding of religious phenomena was purely external; at this time, Kanji's unbelief was due to the unexplainable contradiction in the concept of "God" under his understanding. [9] The point, however, is that Kanji's subsequent conversion was not the result of some more coherent understanding of God cognitively acquired; on the contrary, belief was the result of a direct experience, experience, or understanding The way happened suddenly - in the ICU bed of the hospital, a miracle happened to Kanji, who was dying. This also happens to echo a scene from Kanji’s previous live TV interview. When Kanji said, I don't believe in God because I can't see God, an old woman watching the show and wearing a sari commented, "You are an atheist, how can God appear to you?"

(b) From this, the aforementioned difficulties in connecting "gods" with "religions" can be further understood. (b1) On the one hand, as pointed out in the above discussion of belief experience, the experience of "spirits" in belief itself takes place fundamentally in the first-person perspective, while "religion" in the general sense is The third-person abstraction of the beholder. Therefore, as far as believers themselves are concerned, there is actually no question of how the so-called "religion" is related to "spirits": "spirits" are the direct objects of their belief life, while "religion" is not such an object. Therefore, it is not necessary to explain how "belief" is explained by "religion", because the understanding of "god" is direct, and "religion" is based on "belief" and the product after "belief". In fact, as this article will point out in Section 2, in the long history of human religious life, the origin of the concept of "religion" is not only partial (mainly from the Christian tradition of Western Europe), but also recent ( early modern period). Here again the analogy with the phenomenon of consciousness can be drawn: the emergence of the famous dualistic view in the history of philosophical discussions is the product of the third-personalization of the first-person phenomenon of mind. [10] Similarly, for the phenomenon of belief, the concept of "religion" also appears when the belief itself needs to be examined and defined from a third-person perspective due to certain historical factors.

(b2) This article will explore possible problems with this concept of "religion" in Section II. However, as far as the current discussion is concerned, the question still remains: without adopting the third-person perspective presupposed by the concept of "religion", how to understand the different forms of "spirits" manifested in reality (they may still cause religious organizations, rituals, etc.) or various differences in rational expression)? What Iliad states here is that, on the one hand, each theophany "reveals a certain modality of the divine," that is, an expression that appears divine in nature (in a dialectical manner); on the other hand, Theophany is always "a historical event, so it reveals the attitude of mankind towards the divine at that time". [11] Therefore, each theophany is in one sense connected with each other (as a manifestation of the divine in the tangible), and in another level it is different from each other: due to the different historical circumstances (time, place, occasion) , culture, etc.), the mundane forms of the medium in which the divine manifests vary, and the meanings of the divine as a whole are not similar (even conflicting); this also means that the meaning of the divine reflected in each limited representation must be is shown in history and must go back to history to be understood.

(two)

In the first section, in view of the tension between "god" and "religion" presented in the film, the paper expounds the difference and relationship between "faith" and "religion" by explaining the nature of "sacred". This explains why Kanji had difficulty understanding faith at first, yet was able to gain an epiphany in a direct experience of the divine. Here, the most crucial thing to understand about faith is to see it as a direct and prior experience. This section will discuss on this basis: this section will reflect on the concept of "religion" in combination with the discussion of the origin of the concept of "religion" by Peter Harrison in "The Domain of Science and Religion", thereby illustrating the The above interpretations of beliefs are critical not only for understanding the experiences of individual believers (as discussed above), but also for understanding and even changing the belief lives of larger groups.

Harrison's "The Domain of Science and Religion" examines the conceptual history of the concept of "religion" in the European tradition in detail, and identifies the changes that have taken place within it. (a) In the classical to medieval period, the Latin word "religio" itself meant something closer to an "inner quality of the mind", namely "religion" or "worship". The so-called "true religion" that Augustine talks about in " De Vera Religione, On True Religion " is actually an attitude of inner piety, that is, whether the mind "is properly directed and motivated, or is it unbiased?" It lies halfway between the extremes of superstition and atheism." [12] (b) The transition began roughly in the seventeenth century. The historical factors responsible for this shift may be multiple: for example, in the context of religious fervor during this period, various beliefs and their practices conflicted, coupled with the Church's need to maintain stability, forms of religious debate developed; scientific practice The rise of intellectualized traditions intensified; tensions with European external faith traditions intensified; and so on. In short, a concept of "religion" similar to today's general understanding developed from this, and the concept of "religion" of "religions" and class attributes began to appear: belief has changed from being "an infused virtue" to Gradually evolved into "intellectually agree with the proposition". [13] Combined with Smith's investigation in The Meaning and End of Religion, this transition seems to be largely a unique phenomenon in Europe: no other cultural traditions around the world have found similarities to European17 Concepts such as "Hinduism", "Buddhism" or "Taoism" formed after the 19th century in the understanding of "religion" as an independent entity are all products of Western perspectives that appeared around the 19th century. [14]

However, this concept of "religion", which was formed late in Europe, may have bigger problems. (a) On the one hand, as the "theophanic dialectics" elaborated in Section 1 shows, the divine always manifests itself partially in the secular, and its form and meaning vary in different historical contexts, but as a certain The concept of "religion" that is "schematized" to some extent is difficult to grasp, and may even obscure the flow and change of theophanic meaning; the definition of "religion" itself or "a religion" is almost inevitable. It means the abstraction of belief practices that are very different in different times and different regions. [15] A history or field study of the phenomenon of belief would well support this view: in the case of medieval European Christianity, a common understanding of it was that there was some kind of church-led unity "Latin Christendom" ', and heresies are interpreted as individual deviations from this mainstream; but in fact richness and diversity are the fundamental normalities of this "Latin Christendom." Robert Swanson paints a wonderful picture of the reality facing the church:

[…] (Church) has little ability to effectively control the way in which popular spirituality actually develops, and its role is usually coping, that is, to respond to existing developments among the people. At times it may be controlled and directed, but more often than not, the spiritual activity of the church arises from the 'grassroots' level, from folk worship, devotional activities and demands for atonement and amnesty. […] Often, it has nothing to do but to tolerate and protest other excesses and misdirections. Ultimately, the religious practice of the medieval church was needs-oriented, guided by the spirituality and needs of the laity. [16]

This feature is also shown in the film. At the end of the film, Kanji's belief form of "de-idolizing" is in strong conflict with local religious traditions, revealing the heterogeneity that exists within the same belief group: although the film stops abruptly here, we can't Learn how the two forms of practice ultimately conflict, but it is crucial to see the phenomenon of belief within groups (the term Smith advocates using is "tradition") in a fluid and differentiated way that is not only consistent with history and reality, but also This leaves room for future changes in belief forms.

(b) On the other hand, and more importantly, the concept of "religion" distorts belief by masking the "innately personal, living nature" of the life of faith and the transcendental dimension involved in it. [17] Smith's claim here is to use the term "tradition" to describe belief practices in the third person, while retaining the concept of "belief" in the first person, using "personal rather than impersonal terms" to emphasize the character of faith. [18] This is not only because "belief" is a more adequate description of the experience of the believer as an insider, but it can also avoid misleading bystanders as an outsider. This claim has important practical implications for modern societies with increasingly violent religious or cultural conflicts: it means that we may be able to dispel atheist views of religion as an "anti-scientific", "superstitious" phenomenon, or The arrogance of believers in seeing gods in "other religions" as "idols"; beliefs are not some mysterious and incomprehensible phenomenon, and differences between different "religious" groups can also be reassessed. In an experience involving transcendental beings, where people define themselves in relation to the world and each other, they are able to understand not only how individuals survive in this world, but also how life in this world affects the "soul" in the afterlife. Destiny, to understand, act and change in this world. [19]

In this sense, the film actually leaves an open ending. Time and time again, the audience witnessed the violence brought about by the conflict of beliefs: the life-threatening consequences of Kanji and his family, the Muslim lawyers who had their legs broken, and the frenzy of the smashing idols was to some extent the result of Kanji. How should we coexist with different beliefs - this is the last and most important reflection on "faith" and "religion" left to the audience by "Oudi God".

[1] Translated by Dong Jiangyang and written by Smith: The Meaning and End of Religion, Beijing: Renmin University of China Press, 2005, pp. 296-297. Here is a brief description of the meanings of some basic words used in this article: (1) "Religion": The word "religion" used in this article, unless otherwise specified, adopts a general understanding, that is, a third-person perspective. "Systems of Beliefs and Practices". Although there are some problems with this concept (as will be pointed out later in this article), this article chooses to adopt this understanding for the sake of clarity of writing and gradually reveals the tension between this concept and the concept of "belief". (2) "Belief": refers to the phenomenon or experience of belief in "God/Holy/God" in the first-person perspective. (3) "God/Holy/Spirit": This article does not make a detailed distinction between these three concepts.

[2] Some clarifications on this propositional form of Kanji's argument: (1) Proposition (B) can be understood as a disjunctive proposition, that is, Kanji only needs to argue that "God is bad" or "God (from other reasons) cause an earthquake”, proposition (B) can be established. This article focuses on the process of Kanji's argument for "Gods are bad"; the problems in the argument for "Gods (for other reasons) cause earthquakes" are similar, see footnote 4 for details. (2) Although Kanji did not expressly express proposition (B'), but due to the necessity of demonstrating proposition (B) (that is, considering that the purpose of Kanji's argument is that gods are responsible for earthquakes), it can be added here. Such an implicit inference.

[3] The above analysis shows Kanji's difficulty in arguing for the proposition that "gods are bad"; the same difficulty actually occurs in the process of arguing that "gods (for other reasons) cause earthquakes". Since opposing defense attorneys rejected the "gods are bad" proposition ("we're not talking about good or bad, but whether gods actually cause earthquakes"), Kanji needs to provide the fact "gods cause earthquakes" from other perspectives evidence. To this end, he cites classic texts from the Indian, Christian and Islamic traditions: However, it can be questioned whether the scriptures themselves can be fully equated with the will and actions of the gods?

[4] Yan Kejia, translated by Yao Beiqin, Eliade: "Sacred Existence: The Paradigm of Comparative Religion", Guilin: Guangxi Normal University Press, 2008, pp. 20-25. Every manifestation of the divine in the tangible is the coexistence of multiple contradictions: divine and mundane, existence and non-existence, absolute and relative, eternity and existence.

[5] Ibid., p. 11.

[6] Although Iliad does not directly discuss whether or not theophany is a phenomenon of “first-person nature” in The Divine Being, this paper argues that this understanding and Iliad’s theory are mutually exclusive Coherent. The "revaluation of theophanies" discussed by Iliad focuses on pointing out that the expression of the divine in the historical process is a "history of devaluation and revaluation of values", the understanding of theophanies and the religious theory in a certain historical stage. Adapt to each other (ibid., p. 21). Combined with Smith's discussion of the personal character (i.e., the "first person") of "faith" in "The Meaning and End of Religion": the maintenance and development of any religious phenomenon is fundamentally based on the individual's experience of belief, despite this It does not mean a kind of "individualism", that is, each individual has a different understanding of the sacred, but in the final analysis, the belief tradition must be continued through the identification of the individual, or changed due to some tension with the individual. Therefore, if the interpretation of theophanic meaning by religious theory itself is mediated by individuals, then the theophanic meaning can be said to be the product of a specific historical stage from a macro perspective, and it can be said to be based on the specific experience of each believer on a micro level. For Smith, please refer to: Dong Jiangyang's translation, Smith's book: "The Meaning and End of Religion", Beijing: Renmin University of China Press, 2005, pp. 331-347.

[7] Ibid., p. 367.

[8] Ibid., p. 354. As an example Smith cites: the Muslim theologian al-Ghazzali received a similar insight from an elderly peasant woman that pure theology has a certain superficiality; Surrey has such an admirable dialectic and "more than 20 pieces of evidence about the existence of God" that she has absolutely no clue, yet she lives in the presence of God. See ibid, p. 292.

[9] In Kanji's last statement before he faints, Kanji uses an "external" argument to explain why he doesn't actually believe in the existence of gods (i.e. Proposition A, although if he were to be consistent In order to achieve the goal of its own argument, it is necessary to prove the existence of gods): (A'') According to a general understanding, "gods" are good. (B'') According to proposition (A'): Religion is bad. (C'') gods are either good or bad: if gods are good, then (A') is impossible, but (A') is empirical reality; but if "gods" are bad (proposition B '), then it contradicts (A''), indicating that the belief in "God" is self-contradictory.

[10] See Searle, translated by Wang Wei: "Rediscovery of the Mind", Beijing: Renmin University of China Press, 2005, pp. 100-104. Searle pointed out that the reason why the existence of subjective consciousness that we experience in life is always questioned is entirely due to the definition of the "phenomenon-existence" dichotomy in general scientific activities (especially since the modern scientific revolution). The pragmatic consequences of the method: Taking the phenomenon of color as an example, defining "color" as a "spectral feature" does not mean eliminating the subjective experience of "color", but because of our understanding of the physical reasons behind the subjective phenomenon, Rather than being more interested in subjective phenomena themselves (eg, for historical reasons, in order to more effectively transform the world), subjective phenomena are eliminated from the definition and "spectral features" are defined as the existence of colors. However, this "phenomenon-existence" dichotomy loses its validity when the object of study turns to consciousness, because for consciousness, subjective phenomena are themselves existences.

[11] Iliad: Divine Presence: Paradigms of Comparative Religions, p. 2.

[12] Translated by Zhang Butian and written by Harrison: The Territory of Science and Religion, Beijing: Commercial Press, 2016, p. 158.

[13] Ibid., p. 164.

[14] Smith: The Meaning and End of Religion, pp. 122-133.

[15] Ibid., pp. 297-303.

[16] Long Xiuqing, translated by Zhang Yen, Swanson: Religion and Piety in Europe: 1215-1515, Shanghai: Shanghai Sanlian Publishing, 2012, p.10.

[17] Smith: The Meaning and End of Religion, p. 292.

[18] Ibid., p. 291.

[19] Swanson: Religion and Piety in Europe: 1215-1515, p. 2.

View more about OMG: Oh My God! reviews