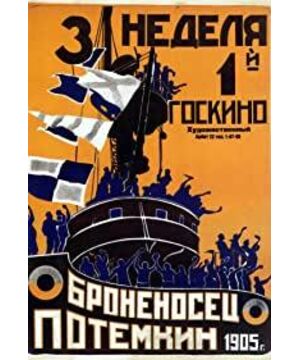

The story itself is simple. The content of the film is adapted from the uprising of the soldiers on the battleship Potemkin in Russia in 1905, and the support of the citizens of Odessa for the soldiers after the uprising, and the repression of the citizens by the tsarist government.

The biggest difference between this film and the previous ones is that Eisenstein believed that montage has the ability to express meaning, and the audience can understand the story based on the picture. Therefore, the entire film has very few subtitles, and even many dialogues have no subtitles. But Eisenstein was right: History records that when "Battleship Potemkin" was on tour in Europe, every screening ended with a standing ovation from the audience.

The audience is excited because the film is full of passion and poetry. This is due to Eisenstein's unprecedented use of various montages in this film.

There are contrast montages. Such as the comparison of expressions: it was found that the beef prepared for cooking was covered with maggots, the soldiers were excited, while the officers were cold. This group of comparison shows the separation between the officers and the soldiers. Some soldiers refused to eat and went to the kitchen to pick up cans. An officer walked past them. The soldiers looked wary, while the officer looked gloomy. This group of contrasts exaggerated the tension between the soldiers and the officers.

There is cross montage, which is to divide two or more simultaneous actions and scenes into different pictures and appear on the screen alternately. For example, in the scene where the firing squad defected: on one side, the captain announced the firing squad, ready to shoot those soldiers who refused to eat, and the officers carried out the order in an orderly manner; on the other side, the soldiers whispered and whispered. The screen switches back and forth on both sides, suggesting that the soldiers are about to rebel. Or the soldiers who died in the uprising were sent back to the coast, and the citizens of Odessa came from all directions to pay their respects: people came from steep steps, from long breakwaters, from bridges. The screen switches back and forth between these places, and finally, the crowd gathers around the tents of the sacrificed soldiers. The picture is packed with people, filled with a tension and a sense of power.

There are metaphor montages. For example, the film is black and white, but the soldiers after the uprising raised a red flag on the battleship, and the red color is post-production. Eisenstein used it to represent people's strength, desire, courage, hope, etc. Another example is the set of shots of the stone lion mentioned in all textbooks.

Among them, "Odessa Step Massacre" is the most concentrated display of Eisenstein's montage genius. The stairs by the pier are wide and steep, and the long ones seem to have no end. The steps were filled with citizens who supported the Potemkin uprising. Suddenly, a gunshot rang out. I saw the tsarist army holding guns, lined up in neat rows, coming down the stairs one by one. People descended the stairs and ran for their lives.

A mother ran with her son, and the son's hand slipped, and she didn't feel it. When she suddenly found out and turned around to look for it, she happened to see her son fell down with a shot. The rushing crowd stepped over his son's body. At the beginning, a few pairs of feet were careful not to step on him, but after more and more feet, running faster and faster, trampling began. This is the cruelest part.

A group of tsarist cavalry appeared below the stairs, blocking people's way and slashing wildly with their knives. A young mother pushes a pram with cavalry in front and infantry in the back. She didn't know what to do. In desperation, she was shot and fell down, bumping into the stroller. The car rushed down the stairs with the baby. ...

this passage adopts the method of superposition of emotions: first, there are sporadic deaths, and some people fall; then there are occasional deaths, and there are people falling from time to time in the running crowd; finally, there is a large area of death, people fall one after another, until the picture There is no longer a living person on it.

Basically, the whole film adopts this superposition method that originated from Griffith. Whether it is conflict, grief, or tension, it is all added layer by layer, and finally there is a big explosion.

After each big outbreak, there is a soothing plot foreshadowing. These soothing plots make the film poetic. It is a tradition of Russian art to express emotions with landscapes. Eisenstein is now bringing this tradition back to the movies.

Soldiers used a small boat to send their fallen comrades back to the dock. The small boat sailed through the sea in the evening, the waves were surging gently. In the harbor, the sailing ship moored quietly, and a dog ran by. ; In the morning light, the mast full of ropes is hidden in the mist; after the battle, the moonlight spreads on the sea, sparkling... These beautiful pictures remind people of the Russian painter Levitan's oil painting: In the painting sandy beach, stones, women, sad Russia. Before Eisenstein, no one had photographed the scenery in a movie so emotionally and touchingly.

These emotional landscapes take the film beyond story and into poetry. This is a poetically beautiful film. That poetry is enough to transcend ideology, topping all "Best Movie" polls and never dropping out.

It never regretted the people who chose to watch it.

View more about Battleship Potemkin reviews