In addition to sentimentality, nostalgia or disgust for a certain doctrine, what Poles and Chinese have in common is more of a state of mind. It may originate from the painful memory of being ravaged by aggression in the 19th and 20th centuries, or it may originate from the embarrassment and helplessness of seeking eternity.

Therefore, in the film, we do see a group of Chinese directors who want to sell emotional accumulation. Some of them are not only active in the history of world film in the last century, but some of them have recently relied on the moral high ground to take the opportunity to suppress and disagree with distorted aesthetics. opinion person. All in all, under their lens, the film is no longer art or beauty, but a pure narrative with a simple and clear purpose, which is to inspire a certain collective consciousness. If the inspiration is successful, then his works are believed to be good work.

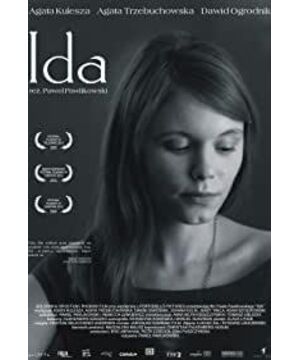

When a film director does not pursue the proposition of beauty, his works cannot but be full of ingenuity. If the infinite enlargement of the story makes the whole film seem without charm, the golden and black and white composition of each chastity is more to conceal the inability to arrange the scene and the movement of the camera. It is also a Polish film. The hall-level "Ten Commandments" No. 5, No Murder, was added with a yellow filter when it was converted, which made the film appear a kind of holy and sad color, and a new "Murder Short Film" was born. And Ida used a gray filter to deepen the black and white effect from the very beginning. There is no doubt that the purpose is clear, that is, walking feels unintentional.

Structurally, there should be countless films in China that show the way of grandstanding and religious elements, reflecting the exploration of minority groups. But at what level, and from what perspective, can moviegoers classify works produced in another context and judge them in their own familiar environment? It seems that even when all the key elements fit into a particular definition, it's hard for the audience to judge just because it's not of their own nature. Whether it's good or bad, I can't tell, because to me, it's similar and not like.

Chinese films after the 1990s (those that can still be called films) are mostly lost in this structuralist predicament. Censorship was never the point, and only a portion of Western art films contained political overtones. Chinese directors gave up the exploration of value from the beginning, and chose to start advocating and marketing the common experience of feelings. The same is true for ida, it will never get the golden lion like Tsai Ming-liang did because of his technique, nor will it evoke the collective sentimentality of the public like some Chinese films in the 1990s because of their content. For the average audience, it is nothing because it has given up the search for ultimate value.

View more about Ida reviews